At the 1995 Source Awards, André 3000 issued a proclamation, or a prophecy: "The South got something to say." Inspired by his words, this list represents some of the most impactful songs, albums and mixtapes by Southern rappers. It was assembled by a team, led by Briana Younger, of Southern critics, scholars and writers representing the Carolinas, Georgia, Florida, Maryland, Mississippi, Texas, Tennessee, Louisiana and Virginia.

We offer this list not as an authoritative canon but as an enthusiastic celebration that recenters the South's role as a creative center of hip-hop and presents the region for all that it has been and given to us.

1995

A pianist taps out a low D and a syncopated D-minor blues chord. A psychedelic guitar lick frets, no, chokes a note for five supple seconds to trip you out, seeming to signal that Jimi Hendrix and Freddy Krueger are back from the dead, the latter surely to shank you. Then the keys add an even lower D and A pattern in the mix with an unassuming drum-and-bass line that lets you know you're not in Hollywood on Elm Street; the Bronx projects; riot-riven, post-Boyz n the Hood South Central L.A.; or even a Miami Beach rumpshakin' set with Uncle Luke. Reporting to you live from "the traps" of "the city too busy to hate," a voice, like buckshot, breaks the ragged silence, only to unsettle you further with 28 words so at war with the 16 counts they fall within that you know you'll never see Atlanta's longtime slogan or hear Southern hip-hop the same again: "When. The. Scene. Unfolds. Young guls. Thirteen. Years old. Expose. Themselves. To any Tom, Dick and Hank. Got mo'. Stretch marks than these hoes. Holle'n they got rank." Surely, not even Scorsese and his whitewashed Taxi Driver lens could make Goodie Mob founding member Khujo's vision any less horrific. And so begins the debut song from four survivors of the so-called war on drugs, who at once detail Black folks' complicity in trafficking, abuse and glorification of illicit crime, declaim any confidence in governmental intervention and refuse to succumb to imminent doom and gloom on the hallowed ground they would famously dub "the Dirty South." In fact, as CeeLo Green, T-Mo and Big Gipp join the phantasmagoria with confessions and observations, they dare to weave a host of Orwellian conspiracy theories for a class-stratified nation too busy to care, decrying the nightmarish corruption and surveillance, historical and present day, that's dependent upon Black communities' implosion and self-destruction. The peerless production of Organized Noize (Rico Wade, Sleepy Brown and Ray Murray) and the spiritual force of their Dungeon Family (iconoclast duo OutKast, rappers Killer Mike and Big Rube, funk singer Joi and others) propel these foot soldiers to stand guard, glocks cocked and ready to take aim at any enemies, one verse at a time. "Who's that peeking in my window? POW! Nobody now!" they chant, putting the industry on noticeand calling fans — and all Southern rappers after them — to come correct and join the front lines. —L. Lamar Wilson, Ph.D.

Soul food is a quintessential element of African-American culture, standing as an example of the way enslaved Africans took the scraps they were given and nourished their families. Today, those dishes are an integral part of the broader American palate, as is Southern hip-hop. On their debut album, Goodie Mob took the term "soul food" and transformed it into a metaphor for the experiences of the working class in the "Dirty South."

Released at a time when Atlanta was still fighting to prove that the city, and the South, had something to contribute to hip-hop, Soul Food stood as an example of the consciousness the region was capable of. Atlanta was largely benefiting from its status as "The City Too Busy To Hate" (they'd go on to host the Olympics one year after Soul Food was released), but Goodie Mob spoke for the Black residents who were surviving off the scraps leftover by the white and Black elite. The rappers weren't afraid to call out the violence of former Atlanta drug unit the Red Dogs or former President Bill Clinton (referring to him as Bill Clampett, a reference to the Beverly Hillbillies character Jed Clampett). On "Free," the opening track that evokes the memory of negro spirituals, CeeLo longs for an escape from opression; on "Live at the O.M.N.I.," the group flips the title of a former entertainment hub in Atlanta into an acronym about mass incarceration, while Khujo's reference to the "trap," on "Thought Process," is often considered one of the genre's first uses of the term on record. A foundational part of Atlanta's extensive and ongoing rap legacy, Goodie Mob's debut provided a counter narrative to the city's standing as a "Black Mecca" and, combined with OutKast's Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, helped show that the South could provide consciousness in addition to the booty bass it had come to be known for. 25 years later, the album is still as nourishing as "a heaping helping of fried chicken, macaroni and cheese and collard greens." —Jewel Wicker

TRU's "I'm Bout It Bout It" is the first big missile from the No Limit Tank that bulldozed through hip-hop from 1995 to 1999. It's also one of the rare times we hear a man (Master P) and a woman (Mia X) share mic duties on the same track and not talk about the usual duet topics of love, sex and relationships. Instead, both offer up violent, but prideful, looks at what life was like in New Orleans, "the murder capital of the world" at the time. Producer KLC provides the perfect backdrop, incorporating a West Coast-ish, Ohio Players "Funky Worm"-esque synth over a New Orleans bounce rhythm that ironically symbolizes P's recent move from Richmond, Calif. back to Louisiana. Even though P didn't offer a definition of what "I'm Bout It" actually means until the last seconds of the song, the raw energy, attitude and litany of city shoutouts in it had most listeners asking themselves if they were "bout it" or not before they officially found out. —Maurice Garland

Initially released as an indie record simply titled Mystikal in the summer of 1994 on New Orleans' Big Boy Records, Mystikal's auspicious debut, Mind of Mystikal, made a huge impression on the Deep South by proving to the region and those outside of it that the Crescent City had more to offer than club-friendly, chant-heavy, p-poppin' bounce music. At a time when bounce artists were outselling many national rap artists in the New Orleans and wider Louisiana market, Mystikal's self-release numbers surpassed those of his homegrown peers, and his popularity and dynamic performances placed him on Jive Records' radar, who quickly signed him to a distribution deal giving him a national platform.

The Mind of Mystikal, which came in the fall of '95, added a few new songs to its predecessor including the classic tracks "Beware" and "Here I Go," the scathing answer to diss records by Cash Money's The B.G.'z and U.N.L.V. Its gold-earning success proved to the industry that New Orleans rap artists could be commercially viable on a national level, making it easier for New Orleans labels like Master P's No Limit and the Williams brothers' Cash Money Records to ink lucrative deals. In addition to garnering critical acclaim from a fickle hip-hop scene that was largely dominated by the East and West Coast, Mind of Mystikal offered proof that the N.O. had top-notch lyricists capable of competing with the best. —Charlie R. Braxton

The video for "Space Age Pimpin'" is set in a floating brothel with women crawling all over invited guests, the future Eightball & MJG envisioned on "Pimps in the House," from their 1993 album Comin Out Hard. MJG opens the song with such chivalrous advances — "I be obliged if you step outside, your ride is awaiting" — and Nina Creque's crooning atop T-Mix's buttery production made of twangy guitars and pillowy horns over warm bass lines is so pleasant that it's easy to forget the endgame. Eightball offers a reminder in the back half: "slip on the latex and dive in. Swish."

The track showcases Memphis rap's deep musicality, the prevalence of pimp culture that took hold in the city, and Eightball & MJG's dogged pursuit of hedonism. They don't "smack, step back, and watch that ho hit the flo'" like on "9 Little Millimeta Boys," instead offering something like romance. Eightball suggests that he and his paramour get to know each other; MJG's lover asks if he'll kill for her, and he replies, "Yeah, if my life in danger too." The whole thing feels hazy and dubious, which so much pleasure is. —Melvin Backman

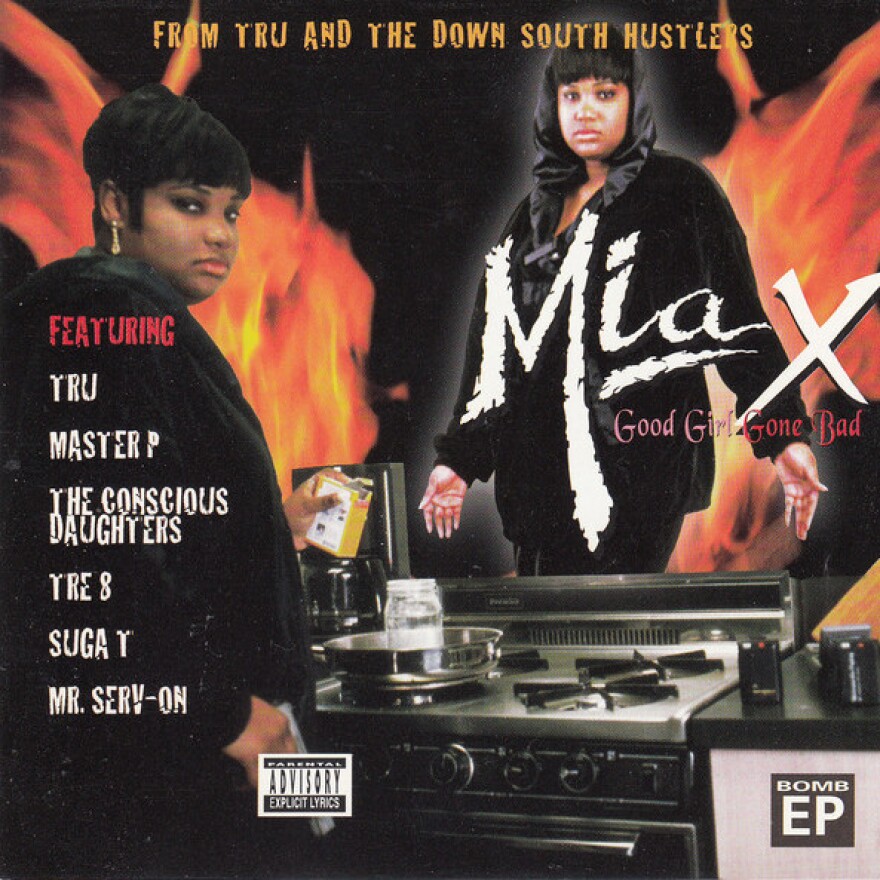

There was a tremendous output of Black women's writing from the 1970s to 1990s that consciously centered Black women's experiences from enslavement to the post-Civil rights movement as essential to understanding the way power works in our nation. Now canonical texts, these works include Ntozake Shange's choreopoem For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf (1976), Alice Walker's novel The Color Purple (1982), Angela Y. Davis's book of essays Women, Race, and Class and Barbara Smith's incisive Black queer women's anthology Home Girls (1983), Kimberlé Crenshaw's essays on intersectionality and jurisprudence (1989, 1991), Patricia Hill Collins' academic monograph Black Feminist Thought (1990), Beverly Guy-Sheftall's anthology of Black women's writing from the 1830s to the 1990s (1995) and Mia X's debut album, Good Girl Gone Bad (1995).

Within the first few bars of the first track, "Ghetto Sarah Lee," Seventh Ward's Mia X, the first woman emcee of Master P's burgeoning No Limit Label in New Orleans, distinguished herself as the indisputable "Mama of Southern Gangsta Rap," a title that only she can hold. Her dizzying versatility across New Orleans bounce to West Coast-influenced gangsta beats and the blend thereof are second only to her narrative dexterity and clarity about who she is as a Black woman oppressed by racism, patriarchy and capitalism in the shadow of Clinton's crime bill. She is every woman — a woman struggling through the challenges of single motherhood, holding it down in a community choked by mass incarceration, managing heartbreak, mourning the loss of a dear friend to domestic violence and moreover a woman seeking and declaring herself worthy of life and pleasure. It's these multitudes that beget the righteous Rapsody, the baby mothering BbyMutha, the sensuality-centering Trina and the gangsta Megan Thee Stallion. Mia X cooks on this album, a method of survival forged by improvising nourishing recipes from whatever she had on hand and in her ancestral lineage to feed herself, her family and Southern hip-hop. We are still lucky to sit at Mama's table. —Zandria F. Robinson

1996

There are only a handful of lyrics from this 1996 twerkfest, which introduced us to the wondrous contradictions of Trick Daddy, that can comfortably be printed. The nonce naughtiness of the titular exclamation underscores that it was always the genius production and one-liners of Luther Campbell that made his Miami bass-driven tracks at once undeniably danceable and unforgettably gutbucket-good. Recasting himself here as a solo act under his nom de guerre Uncle Luke amid his label's bankruptcy reorganization, Campbell paired Trick's laidback pimp flow with the gangsta grime of Verb, whose triple-beat rhymes could rival Twista and Mystikal at their best. The rest is roughly 2-1/2 minutes of histrionic, anaphoric hooks ("Hydraulics!" "Capt. D comin'!") from Luke, including the closing stinger "Free Willy!," an especially clever pun on a PG-rated film about a beloved orca that surprisingly hasn't been resurrected in the recent glut of remakes of early 1990s gems. With the all-star music video featuring everyone from Paula Jai Parker, round-the-way-girl-o-the-day, to Rudy Ray Moore, aka "Dolemite" himself, Campbell let the world know that while he was down with money problems for the moment, he wasn't leaving the game without a fight. To this day, "Scarred" rivals any song in Lil Jon's crunk catalog. Just drop this track in your party's mix, and watch da booties go whop-whop-whop ... —L. Lamar Wilson, Ph.D.

UGK's Ridin' Dirty grooves just as much as it bangs. The third studio album by the Port Arthur, Texas duo was released in 1996 and modeled after the infamous tapes created by the forefather of Houston's native chopped and screwed genre, DJ Screw; the pensive "3 in the Mornin'," is named after his project, 3 'N the Mornin'. Even Ridin' Dirty, itself, is a duplicate title, taken from DJ Screw's collaborative tape with the group, recorded shortly before the release of Bun B and the late Pimp C's own work. True to its origins, the UGK iteration of Ridin' Dirty settles into a decidedly unhurried pace: "One Day" and "Diamonds & Wood" serve as the most contemplative songs on the album, with the artists rapping solemnly and steadfastly about their respective trials, tribulations and errors as human beings. There are a few exceptions to the measured pacing, like the frenetic "Murder," produced by Pimp C; on it, both Pimp and his counterpart spit intense, threatening rhymes about their confident positionings as men and artists. "Well, it's Bun B b****, and I'm the king of moving chickens / Not them finger lickins'," Bun announces vitriolically, before launching into a tear of a verse. Much of the album is produced by the unofficial in-house team of Pimp C and his frequent collaborator N.O. Joe, who craft a sound that resembles a laid-back journey through the streets of South Texas, largely driven by funk and soul samples. Pimp, the more vocal half of UGK, ultimately used songs like the title track and the outro to shout out regions, cities and crews across the South, laying bare his affiliations and how meaningful they were to him. —Kiana Fitzgerald

"We tryna let the whole world hear how we do it down South," ESG, Houston rap royalty, warns in his endearing drawl on the intro of DJ Screw's 3 'N the Mornin' Part Two. The tape is filled with repeated phrasing and expertly placed turntable scratches that permeate the brain in an intentionally syrupy way — all in service of DJ Screw's lofty, but attainable, plan to chop and screw the globe, one song at a time. Not only did Screw produce hundreds of his own tapes before passing away in 2000, he inspired a rival Houston coterie, Swishahouse. That crew eventually birthed the Chopstars of present day, who construct their own prolific "chopped not slopped" creations in memory of the originator.

3 'N the Mornin' Part Two is the epicenter of Screw's extensive tape series and touches on everything from the perils young Black men fought to escape in the mid-1990s ("No Way Out") and still face today, to the small pockets of local joys ("Elbows Swangin'"). The last third of the tape is the most potent, starting with the transformative "G-Ride," which kicks off with a countdown and an enthusiastic "all aboard" before DJ Screw constructs a gauzy scene for ESG to spit all-knowing bars over and for featured singer Flava to sprinkle his soulful vocals. From there, DJ Screw blends his way from the self-explanatory "Why You Hatin' Me" to the eerie "Cloverland," which drips into the album's most well-known track, "Pimp tha Pen" by Lil' Keke, who raps from the heart from jump, with 3 'N the Mornin' Part Two's most memorable lyrics: "I'm draped up and dripped out / Know what I'm talkin' bout?" In their regional specificity and colloquialisms, those lines embody the essence of the entire project, letting it be known that this is a tape for Texans, by Texans. Everybody else is welcome to join the voyage. —Kiana Fitzgerald

If there was a periodic table for what southern hip-hop sounds and feels like, blues guitars and strip club visits would be two key elements. Tela's 1996 hit "Sho Nuff" has healthy doses of both. Produced by Jazze Pha, the track doesn't open with a drum pattern or voice adlib, instead it immediately identifies itself with guitarist Neal Jones' three-note intro that brings you back to the first time you heard it, everytime you hear it. This musicality, matched with Tela and guests Eightball & MJG using the art of storytelling to describe their interactions with "hoes with no clothes," set and damn near created the bar for what a "strip club anthem" is supposed to be — which, before this, mainly consisted of simple chants and direct instructions for "shaking that ass in the club." To this day, "Sho Nuff" remains tied with Ball & G's "Space Age Pimpin'" as the highest-charting single Suave House Records ever released. —Maurice Garland

1997

The origins of trap music have long been disputed, with Atlanta artists T.I., Jeezy and Gucci Mane often credited with taking the genre mainstream. But prior to their reigns in the 2000s, acts such as Goodie Mob and Ghetto Mafia were rapping about the trap.

While the record labels So So Def and LaFace were solidifying Atlanta as a cultural hub in the mid-1990s, Nino and Wicked of Ghetto Mafia were setting their country rhymes squarely in the neighboring city, Decatur. "Naw, this ain't Compton. This Decatur," rapper Nino adlibs underneath the hook of their standout single "Straight from the DEC." An ode to their hometown that centers around tales of drug dealing and raids over a bluesy guitar riff, "Straight from the DEC" doesn't actually include the word "trap" (although the pair utilizes the word elsewhere on their sophomore album of the same name). Still, it encompases the lyrical themes the genre would become known for. Ghetto Mafia never reached the level of fame of their peers of the time such as OutKast and Goodie Mob, but they remain local legends and early pioneers of the city's hip-hop scene. —Jewel Wicker

Ask any fans of Southern rap to list their favorite No Limit songs, and chances are they'll include Young Bleed's "How Ya Do Dat." The Baton Rouge/New Orleans/No Limit anthem served as a declaration that Louisiana was no longer going to be relegated to the rap sidelines. Bleed opens the song with a question familiar to any Louisiana native and New Orleans Saints fan: "(W)ho dat? Heard they wanna do dat." And whether takers were from Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Utah, Arizona or beyond, they could get that bayou smoke.

"How Ya Do Dat" was a key part of the Tank's early success and one of the tracks on the I'm Bout It soundtrack responsible for garnering the label its first No. 1 album. Ironically, despite the single and Young Bleed's subsequent 1998 Priority Records debut My Balls & My Word and their affiliation with No Limit, Bleed wasn't actually a No Limit artist. In-house production team Beats by the Pound only touched up "How Ya Do Dat," which started as 1996 Bleed solo track "A Fool,'' composed and produced with his then collaborator, now Grammy-winning producer Happy Perez. The combination approach made for a result that's a little more melodic than the standard Beats by the Pound production, taking the trademark mix of New Orleans bounce and the harder gangsta element that made you believe No Limit soldiers walked the "Hoes bounce that ass, n***** get dealt with" talk and infused it with a little West Coast funk. The sound is a reflection of Perez's Dr. Dre and Pimp C discipleship, plus some influence from his hometown of Houston, which lends a dark, heavy feel to the instrumental. (Perez also worked on the debut album of Bleed's little cousin, Boosie.) But as often happens with No Limit posse cuts — which were spread throughout the No Limit discography like Easter eggs to drive sales for each of the continuous releases out of the camp — the primary artist got lost in the mix. Master P is often listed as the title artist for "How Ya Do Dat," while Bleed, despite the Gold success of My Balls & My Word, has largely faded into semi-obscurity. Still, the rally cry of "How Ya Do Dat" has listeners ready to act a fool even 20 years later. —Naima Cochrane

In the summer of 1997, hip-hop desperately needed to find its joy again following a presumed East Coast/West Coast rap rivalry left its two brightest stars, Tupac Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G., dead at the ages 25 and 24, respectively. Enter Missy Elliott, her close friend and superstar producer Timbaland and Supa Dupa Fly. There's not much of an argument to be made about whether Missy's debut album is a classic. It is. Full stop. But is it a Southern album is where the discussion gets foggy, much how it's always been for Virginia hip-hop.

Supa Dupa Fly is an amalgam of sounds and genres, from hip-hop, R&B and soul. Listening to the album in 2020, it feels like a project that's still a good 10-15 years from its actual release date, still ahead of its time sonically and culturally. Speaking to Timbaland in 2017 for the 20th anniversary of the album, he didn't mince words when zeroing in on its impact. "We made history," he told me. "We came in and shifted the tempo and the bounce." No cap. "Sock It 2 Me" with Da Brat was erotic and promiscuous, but carried an undeniable bop with it. "Beep Me 911" with 702 and Magoo was vulnerable, yet simultaneously sultry. Records like "Best Friend" featuring Aaliyah and "Friendly Skies" with Ginuwine were further proof that Missy never minded sharing the stage with her friends. In fact, she preferred it that way. A defibrillator jolt to the very nervous system of a reeling Black music ecosystem, the Portsmouth, Va. native's debut project is as importantly-timed a classic as there is. "We were young," Timbaland said. "[Missy's] whole thing was, 'I gotta do this and make it fun.'" Mission accomplished. —Justin Tinsley

In 1997, Kilo Ali made the best rap album of his career. It was his seventh project, and he was only 24. The Atlanta upstart had made a name for himself, releasing his first hit, the conscious jam "Cocaine," at 17. He followed that with a run of four regionally loved albums in the early '90s that yielded his first taste of nationwide recognition, thanks to his cuts "Nasty Dancer" and "White Horse," from his 1995 album, Get This Party Started. With momentum on his side, Organized Bass was the result of a joint deal with Interscope records and Kilo's musical ties to the city, which included the Dungeon Family. "Love Ya In Mouth," like the bass music tradition that heavily influenced his work, was Kilo Ali making an oral sex anthem that to this day still has dope boys and private school girls alike yelling, "She said she never done it / she said never tried / she sitting there telling a m************ lie." It's like watching that R-rated movie you know will get you in trouble with your parents, but it's so damn good you don't care. That Big Boi pops up fresh off of OutKast's lyrical deep dive known as ATLiens only adds more spice to a boiling pot of raunch. —Gavin Godfrey

Master P and his independent No Limit label officially introduced themselves in 1995 with his group TRU's explosive single, "I'm Bout It Bout It," which took its self-titled LP to gold status. The following year, he established himself as a solo artist by releasing the platinum-selling LP Ice Cream Man. At the top of 1997, TRU's follow up effort Tru 2 Da Game went platinum; that summer, P wrote, directed, and starred in the film I'm Bout It, which became a cultural phenomenon that earned him yet another platinum plaque, and with all eyes officially on him, he dropped Ghetto D in September. Could he repeat his incredible success or would he fall off? The album, which yielded the hit single "Make Em Say Uhh!," proved to be lightning in a bottle and the record of his career, selling 250,000 copies the first week out and eventually reaching triple-platinum status. It was the largest selling record in the No Limit catalog — an extraordinary feat in itself — and took Master P from underdog rapper to pop star status and No Limit Records from fledgling indie outfit to bonafide national label. In the boardrooms, majors took notice and began to see the fiscal advantages of inking deals with Southern startups, and in the streets, a slew of down South hustlers were inspired to pour their money into music hoping to repeat P's success. —Charlie R. Braxton

Since its introduction to the mainstream, Southern rap music has built a bulletproof legacy of getting the body moving. From Miami bass to New Orleans bounce, rappers have acted as the mouthpieces for their regions, fashioning anthems that would permeate outside of their home turf. When it comes to Memphis, the locally-developed sound that eventually became a staple in early 2000s pop culture was crunk and few tracks embodied that sound like Three 6 Mafia's early hit "Tear Da Club Up '97," from the group's Chapter 2: World Domination. Its legend not only lies in its ability to inform other cities like Atlanta (where it went mainstream) how to channel rage, but also in the taboo reputation that the song cultivated in its genesis: The song's messaging is almost exclusively based around throwing hands, bows and shoe bottoms at strangers in the club. Turn it on today, and people still honor it in similar fashion. —Lawrence Burney

1998

One of Atlanta's earliest stars, Raheem The Dream paved the way for generations of acts in the city, helping to formulate the then-popular Miami bass into an Atlanta sound (alongside peers like Kilo Ali and MC Shy D). "Freak No Mo" is a subtle but beautiful mix of Miami booty-shaking style and Atlanta attitude that arrived just as the city's famed Freaknik was coming to an end. Its rolling bass giving way to a smoother, slower groove all but closed the door on the era. In 2014, the then-rapidly rising trio Migos took Raheem The Dream's "Freak No Mo" concept and fashioned it into the stripper ode "Freak No More" from the album No Label 2, a reference that brought the long history of Atlanta's spot at the forefront of sonic shifts in hip-hop full circle. Raheem the Dream's behind-the-scenes work of transforming his music into a business with his Tight 2 Def label (which would eventually give us early records from DRAMA, Young Dro, DG Yola and Dem Franchize Boyz) remains his truly foundational work; a song like "Freak No Mo" only reminds us just how far back and forward that legacy stretches. —Clarissa Brooks

In the history of the Screwed Up Click, Lil Keke & Fat Pat are the greatest duo that never was. Both achieved solo success within the Click, and Keke holds the honor of having the collective's first breakthrough single after E.S.G. discussed jamming Screw openly on "Swang N' Bang" in 1995 ("Sip syrup, swang and bang, jam nothing but that Screw fool"). Keke's "Southside" was originally a jailhouse freestyle that evolved into a dance and ultimately a salvo sent to the rest of the world. Fat Pat was the gravel-voiced superstar who would be tragically cut down in February 1998, a month before the release of his classic debut album, Ghetto Dreams.

"25 Lighters" with Port Arthur native DJ DMD marks one of the few times Keke and Pat's chemistry manifested in a full-blown single. Over a chop of Al B. Sure!'s "Nite & Day," all three parties exhibit what make them world-beaters: DMD's opening verse feels like a gospel refrain, as he breaks down why the number 25 is so prevalent in his life; Keke's rundown of day-to-day operation and mantras ("never trust broads"); Pat's coda of strongarm bravado. The song also helped establish slang around "25 lighters," code for holding crack rock within an empty BIC lighter. Pieces of the track have been lifted in various forms by the likes of Kendrick Lamar, Big K.R.I.T., Mac Miller and Z-Ro; there's also a gospel remix and even one by Houston's own classic rock band ZZ Top. —Brandon Caldwell

"Nann N****," Trick Daddy's 1998 release from his sophomore album www.thug.com is an unequal sparring match. This is to say that, on first listen, it's possible to think Trick Daddy steers the flow and sharpness of the record, but with a slight second thought, it's clear that then 24-year-old Trina, who had just gotten her real estate license that year, was the victor. It's one of the highlights of Trina's career and foreshadowed a catalog of hits that would help pave the way for women in hip-hop to see themselves fully. We have no Megan Thee Stallion or Nicki Minaj without the powerful words of Trina. Her feature verse showcased her best attributes: her wit, conversational lyricism and unabashed sexuality that is not in relation to the male gaze but from her own internal compass. Trina's upbringing and clear sense of self-esteem reflected the basis of Black women's ownership of their autonomy and tacitly rejected the ways in which it has always been policed and ridiculed. Her debut album, Da Baddest B**** in 2000, and the music that followed, granted her entry into hip-hop's hall of fame — not only for her explicit lyrics and her ability to spar with her peers but also her commitment to outdoing her past self time and time again. —Clarissa Brooks

Writing a short review of Aquemini feels wrong. This album needs books written about it. Actually, it needs sets of books like Regina Bradley's Chronicling Stankonia and sequels upon sequels to actually explore what OutKast did to sound and song. Over 20 years after the album dropped, there may not be any popular art that is as equally committed to being innovative as it is to being jammin'. Aquemini made those of us crazy enough to wander wonder about the relationship between invention and appeal. How do you give consumers something they've never experienced and make them not just need, but want, to experience it again? While nothing before or after sounded like "Hold On, Be Strong," "Rosa Parks," "Da Art of Storytellin' (Pt. 2)," "SpottieOttieDopaliscious," "Liberation" and "Chonkyfire," it's the character and characters of Aquemini that really secure it as one of the greatest artful constructions ever made.

Of course, we have André and Big Boi, luminous and rhyming back-to-back. But to whom are they rhyming? I imagine Big and Dre in the middle of a levitating cypher rhyming to the characters: Sasha Thumper, the gypsy from "Rosa Parks," the owner of the bootleg album store in skits, Raekwon's Henny drinking self, Nathaniel rapping over the phone from prison, and Badu wearing a shirt that says airbrushed, "Tryin' to stay sane is the price of fame / Spending your life trying to numb the pain / You shake that load off and sing your song / Liberate the minds, then you go on home." Surrounding that cypher of breath-filled Black human beings is a larger cypher of sounds that is one fourth heaven, one fourth jungle, one fourth Jupiter and one fourth harmonicas. —Kiese Makeba Laymon

Gangsta Boo is the Queen of Memphis and the First Lady of Hypnotize Minds, Prophet Posse and Three 6 Mafia. She is the original "f****** lady": horrorcore, smoke, mosh pits and boss s***. Whenever she enters the room of a track, the whole of femme Memphis enters with her. No song exemplifies this consistently dynamic and breathtaking character of Boo's presence more than "Where Dem Dollas At." The song's architecture is reflective of her distinct ability to command a royal Southern court; the city's premier producers, DJ Paul and Juicy J, sampled a popular Memphis song "Sho Nuff," originally produced by Memphis native and son of the Bar-Kays' bassist, Jazze Pha. Its insistent title query, chanted by a chorus of Boo's dubbed voice, is punctuated by a sample of one of her own lines from her featured verse on Indo G's "Remember Me Ballin'." That she can sample herself — "I'm chiefin' heavy understand me, baby, this Gangsta Boo" — and chant a demand for the location of the cash is an explicit recognition of her power and significance as a formidable rapper in an all-men music collective in the 1990s South.

"Where Dem Dollas At" is the template for cash-as-women's-agency that reverberates throughout subsequent women rappers' work, from Trina to Megan Thee Stallion to Cardi B, as laborers in the music industry. The enduring question of the song is of what Gangsta Boo, as well as frequent collaborator La Chat, is owed for her trailblazing work as a tenaciously deft lyricist better than most of her men counterparts. In an industry where women's increased presence as artists rarely translates into increased power, compensation, or control, "Where Dem Dollas At" is a reminder of where we have been, just how far we have to go and how we need to keep chanting the questions until we get the answers we deserve. —Zandria F. Robinson

In 1998, hip-hop was undergoing an evolution. The heaviness of the West Coast/East Coast beef, culminating in Tupac and Big's subsequent deaths in 1996 and '97 had subsided, and during those battle years Southern hip-hop had finally advanced from the sidelines to the playing field. The No Limit soldiers had recently stormed the rap scene waving the New Orleans banner, clearing the way for former bounce label Cash Money Records to announce they were "taking over for the '99 and the 2000s" with Juvenile's 400 Degreez.

Cash Money took No Limit's formula and improved on it, rebranding from a regional label to a JV with Universal in a historic deal said to be worth $30 million that allowed them to retain ownership of their masters and publishing. Immediately, they stopped hip-hop in its tracks with a single that sounded rough and chaotic, but simultaneously polished and advanced. "Ha'' was our visitor's pass to Magnolia Projects. It wasn't danceable and barely even head-noddable, but it was quietly inspirational; Juve was talking to block boys everywhere out there handlin' their biz. Even East Coast rap giant Jay Z was motivated to jump on the track for his own rendition.

Juve and Mannie Fresh were an elite artist-producer team; Juve is a master storyteller with a cadence that effortlessly shifts from growling realness to melodic and playful, and the perfect conduit for Mannie Fresh's futuristic bounce-influenced production. The in-house architect of Cash Money's sound crafted our journey through Juvenile's New Orleans, from the invitational "Gone Ride With Me" to a hood orientation session in "Welcome 2 Tha 'Nolia." Juve showed us his stark reality in "Ghetto Children," brought us along for a day's business (and the risk that goes with it) on "Follow Me Now" but also reminded us that New Orleans is still a rhythmic city with the ass-shaking anthem that's drawn people of all ages to the dance floor for the last 20 years, "Back That Azz Up."

Juvenile's takeover declaration proved at least partially true — according to Billboard, 400 Degreez was the top R&B/Hip-Hop album of 1999, remaining on the charts even as Juve released another LP, and it remains Cash Money's top album to date with over four million units sold. The small label's first foray into the major's space helped lay the groundwork for an outsized legacy; though Juvenile's time with them came to an end just a couple of years later, 400 Degreez's heat kept burning. —Naima Cochrane

"Back That Azz Up," from New Orleans rapper Juvenile's debut album 400 Degreez, is the Pavlovian song of Southern hip-hop. (Crime Mob's "Knuck if You Buck" clocks in at a distant second.) The first 15 seconds of the song, a blend of bass and strings, breaks open into a rapid spitfire of Juvenile's New Orleanian drawl and the local flavor of New Orleans bounce music. Juvenile's use of "ha" does double duty throughout the song — a throwback to Juvenile's debut on "Ha" and also a taste of how it sounds to be hollered at and encouraged to dance in a New Orleans party, whether it's out in somebody's backyard or a college function. The single is not only Mannie Fresh's masterpiece, but it is the ushering in of the Cash Money Records era of "the 9-9 and the 2000." "Back That Azz Up" passes the essential club and car test — so effective, in fact, that Chrysler used it to highlight their back up camera feature in their cars — and reigns, over two decades later, as the one track that makes all of us wish we had Megan Thee Stallion's knees, if but for 4 minutes and 25 seconds. —Regina N. Bradley, Ph.D.

1999

Chopper City in the Ghetto's most celebrated achievement is "Bling Bling," the single credited with catapulting a then nascent Lil Wayne, who raps the song's titular phrase on the hook, into the spotlight and providing language for a particular brand of rap's particular brand of materialism. It's ironic, though, this album housed that song (which was originally intended for a Big Tymers release) because B.G. was always street-cool before he was ostentatious. At only 18, it was his fifth album — his first under Cash Money's historic deal with Universal; the prior four helped them cement it — and the one that best displays his vocal instrument and the delicate and compelling push-pull of his music and trajectory.

B.G.'s voice and the way he enunciates his vowels may translate the majestic accent of New Orleans better than any of his peers; it's laidback and defined by a singular kind of nasally drawl that adds rawness to his casual cadence. It's a perfect complement to Mannie Fresh's production wizardry, which is pristine as ever here. The cinematic evolution of "N***** In Trouble," from its orchestral stabs to its breakdown into vintage bounce, is a rapper's playground, while the intricate buoyancy of "Cash Money Is an Army" rings out like a well-timed and well-earned victory lap coming off the massive success of Juvenile's 400 Degreez. The latter track, along with "Cash Money Roll," offers a glimpse of the once unbreakable familial bonds of the label which added to their legend; their most self-immortalizing music often exerts an air of triumphant invincibility. But in B.G.'s case, there's always been one foot in and one foot out, luxury and lack in the same breaths. Songs like "Thug'n," "Hard Times" and "'Bout My Paper" tend toward the dark and brutal truths of his life and that of the people he grew up around. The pull of the streets — and the addiction he picked up in them — was always at odds with the rap star lifestyle, and Chopper City in the Ghetto intertwines them both for a paradoxical yet potent result. —Briana Younger

Grey Skies was personal.

I was best friends with Brandon "B-Dazzle" Franklin, little brother of Kamikaze, one half of Crooked Lettaz. In high school in 1992, Brandon would bring tapes to school of what Kamikaze and David Banner were working on. Most of us wanted to be rappers far more than we wanted to put the work into actually creating music to rap to. Banner and Kamikaze were different. Like Chris Jackson, James Robinson and Othella Harrington, they were virtuoso Mississippi Black boys we could see, smell and touch. Since they intimately knew Ellis Seafood, Bebop records, Lake Hico and the Sonic Boom of the South and we knew the same thing, we felt more worthy, less less than about being alive.

Seven years later, on April 20, while I was in graduate school at Indiana University, I heard Grey Skies for the first time. Grey Skies is why I didn't write myself out of my fiction and nonfiction. Grey Skies made the evocative proclamation that in order to understand the Jackson, Miss. that birthed us, one needed to understand the sounds of the Mississippi Gulf coast, Tupelo, the Mississippi Delta and the Democratic Republic of Congo. They made a classic sonic quilt out of everything Black Jacksonians like us knew. I knew Mama Lena. I knew Kamikaze washed Pimp C and Noreaga on "Get Crunk" and "Fire Water." I knew Valley North. I knew from whence Banner's provocation "My state left scars on my manhood while y'all screaming that it's all good" came. I knew Tupelo. Mostly, I knew the eerie and iridescent feeling of trying to impress New York while longing to represent Jackson, Miss. Grey Skies introduced me to the feeling of pushing beyond impression and representation toward revision of New York and Mississippi conceptions of art and black boyness. At its best — though neither New York or Mississippi were ready — Grey Skies showed the world that we were diligent listeners and genius creators who could be responsible exemplars of hip-hop. But Jackson, Miss. would always be who and what was responsible for us. —Kiese Makeba Laymon

Distinctively shaped through an interwoven collection of highways, Houston and its hip-hop is intrinsically linked to the city's car culture: slabs. An acronym for slow, low and bangin, it is the baptism of an old Cadillac into a candy-dipped custom car on rims ("swangas") accompanied by a "fifth wheel" (encapsulated rim in fiberglass case) and accentuated with a neon trunk display (reading messages like Kornbread's "THI5 WHY YA HOE MISSIN"); yet its crown jewel is a powerful stereo system, the hustler's sole companion as he drives slowly across the interstate.

On long nights in the city, the soulfulness of "Wanna Be A Baller"'s hook, sung by Big T, comforts the lonely driver: "I hit the highway, making money the fly way / But there's got to be a better way! / A better way, better way, yeah." As Big T fades into the ether, Yungstar, Fat Pat, Lil' Wil and Big Hawk contribute their individual perspective on the hustler's mindset during his ride along I-10, set to a slowed-down sample of Prince's "Little Red Corvette." Although most of the rappers that appear on the track (Lil' Troy himself does not) are now deceased, their spirits are immortalized in one of the most recognizable songs in contemporary hip-hop — a true Houston classic. —Taylor Crumpton

If The Last Mr. Bigg's name isn't instantly recognizable, perhaps his voice is more familiar as the hook from Three 6 Mafia's "Poppin' My Collar." That hit netted the Mobile, Ala. rapper his biggest commercial success, but it was his 1999 single "Trial Time" (originally titled "Take That S*** to Trial") that first took the entire Southern region by storm, turning up every club, juke joint and hole-in-the-wall in between from Houston, Texas all the way to Charlotte, N.C. Having emerged from Mobile's thriving underground rap scene, the song is built around an irresistible beat made of hypnotic hi-hats, a booming 808-induced bass line and eerie synthesized horns — a gritty but perfect backdrop for Mr. Bigg's vivid account of the pitfalls, legal and otherwise, of trapping. "Trial Time," which in fact shares its foundational DNA with trap music, helped kick open the door for a state with few breakout stars. —Charlie R. Braxton

Nearly a decade before "Int'l Players Anthem" brought Atlanta, Memphis and Houston together for an intraregional marriage of Southern rap, Cash Money came up the Mississippi River from New Orleans to Memphis to create a Delta Voltron with Hypnotize Minds. It's an intentional collaboration of independent labels outside of Atlanta — which had long had access to major label capital — that acknowledges the exchange between the cities at the top and bottom of the river in the Deep South. A reprisal of a track that appears earlier on the Ghetty Green album and features Gangsta Boo, the outro version features Birdman, Turk, Wayne, Juvenile, Juicy J, DJ Paul and Project Pat in succession, with Pat helming the hook with his distinctive skill and cadence. It is a triumphant meeting of the gold and platinum grills, the river city ballers, and a prophecy of the divergent futures that were to come. The platinum Cash Money Records continues its success and major label relationship with Universal; the gold Hypnotize Minds essentially closed shop last decade, its former artists variously independent or signed to major label deals, including with Columbia. And like its predecessor Stax Records, Hypnotize Minds' catalogue is widely sampled.

As an artist whose influence has reached far beyond the container of record labels, Project Pat is the quintessential blueprint and anchor for so many Southern hip-hop hits. From "Int'l Players Anthem," which re-used a beat DJ Paul and Juicy J had produced for Pat's song "Choose U," to J. Cole's use of the "don't save her" hook on "No Role Modelz" from Pat's 2001 song "Don't Save Her"; to Cardi B's "Bickenhead," which famously references Pat's collaboration with La Chat, "Chickenhead" — Pat might be the truest "most known unknown." His influence, foresight, and rich ethnographies of North Memphis have not seen nearly the depth and breadth of recognition, or understanding and critical engagement, they deserve. Nevertheless, his outsize presence in southern hip-hop, and hip-hop more generally, will be observable for decades. —Zandria F. Robinson

"Down for My N's" is the anthem that trounces all anthems. The repetitive chorus —"F*** them other n***** 'cause I'm down for my n*****" — is straight-forward yet effective, a rallying call that's shouted across the nation. Built around a Herculean production effort by KLC, a member of No Limit Records' prolific in-house team Beats by the Pound, C-Murder and featured artists Snoop Dogg and Magic, concocted a song that rings out everywhere, from clubs and sporting events to stadium tours; no matter the setting, it's equally electrifying. "Down for My N's" starts with C-Murder's throaty, gritty bars, followed by Magic's amped-up and borderline unhinged delivery. The smoothness of Snoop's verse, which closes out the track, is juxtaposed against the others', proving there's more than one way to sound intimidating. The song ends by fading out, with the chorus still being chanted, the voices carrying on as though they could profess their loyalty forever. It's a Southern gem, but it sparkled brightly enough for the world to see. —Kiana Fitzgerald

After building a loyal fanbase with two underground classics (1996's Fly S*** and 1998's Movin On), Playa Fly's third offering, 1999's Da Game Owe Me, acted as Exhibit C in the case for the Memphis rapper being one of Southern hip-hop's most distinct voices. Exclusively produced by longtime collaborator Blackout, Da Game Owe Me features Fly delivering his patented flows at different speeds across a range of topics. On "Ghetto Eyes," he puts on his philosopher hat to explore racism and religion while dropping lines like "what does it mean when someone says they see a brighter day / All that I know is that it's not as dark as it was yesterday." He keeps this tone on other tracks like "N God We Trust," but he also takes plenty of opportunities to just rap circles around your favorite rapper with lyrical showcases like "Get Me Out" and "Talkin Cash On It." Rocking a full cap and gown on the cover, this album was supposed to be Fly's graduation from regional to national success. Unfortunately, that trajectory was interrupted by a prison stint that took him out of the game for seven years, but Fly's showing on Da Game Owe Me proves that originality has no expiration date; 20 years later, he's still filming music videos for songs off this album, and they are spreading and making an impact as if it came out yesterday. —Maurice Garland

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.