Andy Warhol is arguably the most influential artist since World War II. But Warhol was full of paradoxes – at once aggressively public and deeply private, and a serious artist who presented his life and art as all surface: the soup-can paintings, the candy-colored Marilyns, the glitzy Manhattan social scene. Beyond his towering status, there’s not much consensus about who Warhol, a man whose works have sold for $100 million or more, really was.

"Andy Warhol: Revelation" runs Oct. 20 to Feb. 16. The Andy Warhol Museum, 117 Sandusky St., North Side

A new exhibit at The Andy Warhol Museum adds another twist to attempts to decipher Warhol. “Andy Warhol: Revelation” contends that a central building block of the artist’s persona was his Catholic faith. It’s billed as the first exhibit to focus solely on Warhol and his religion.

Many visitors to the Warhol, according to the museum, don’t know that Warhol was the child of immigrants, or that he grew up in Pittsburgh. So it’s not surprising they’re unaware that he was raised in the Byzantine Catholic Church – or that he remained a churchgoer his entire life. But the evidence is copious.

In his eulogy at Warhol’s memorial service, on April 1, 1987 – which drew 2,000 to St. Patrick’s Cathedral, in New York City – art critic and historian John Richardson spoke of Warhol’s “secret piety.” Richardson contrasted it with “our perception of an artist who fooled the world into believing that his only obsessions were money, fame, and glamor, and that he was cool to the point of callousness.”

"This is something Andy Warhol would have seen as a young boy going to church with his family."

Warhol Museum chief curator Jose Diaz attempts to dispel such misconceptions – first of all, by taking us to church. Some of the first artifacts visible in “Andy Warhol: Revelation” are panels from the original, two-story-tall icon screen that graced the altar of St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church. The landmark house of worship, located in the isolated part of Lower Greenfield known as The Run, boasts a handsome, yellow-brick façade, and it’s topped by three gilded Byzantine crosses. It’s visible from the Parkway East, and it’s the church Andrew Warhola and his working-class family attended for most of his childhood in the 1930s and ’40s, walking down the wooded hillside from their rowhouse in South Oakland.

The salvaged panels depict four prophets (including St. Peter and St. Andrew) with gilded halos.

“This is something Andy Warhol would have seen as a young boy going to church with his family,” Diaz said. He believes Warhol adapted the experience to secular idols. “Icons are a way to speak to holy figures in terms of adoration and prayer. … To take images of Jackie or images of Marilyn and understand that they would speak to the masses, I think that was a tool he would have learned just by observing life in church.”

"It's how Warhol can operate on two planes at once."

In the gallery, the panels (on loan from St. John’s) hang near vitrines containing Warhol family treasures, including a plaster enthroned Jesus that Andy painted as a boy; a sizable crucifix he owned as a child; and the crucifix from the casket of his father, a laborer, who died in 1942, when Andy was about 14. There is also art by Warhol’s mother, Julia Warhola, a key influence in his life who lived with him in New York for two decades until her death, in 1972.

Other scholars find Catholic roots to Warhol’s pioneering technique of creating multiples of the same image: eight Elvises, 15 Jackies. The technique was groundbreaking because in fine art, it was thought that to endlessly reproduce an image was to cheapen it. Warhol upended that calculus, some experts say, by drawing on a popular art form he knew well: Catholicism’s ubiquitous prayer cards, in the case of which replication only deepened devotion.

Miranda Lash, curator of contemporary art at the Speed Art Museum in Louisville, Ky., cites the extreme example of Warhol’s 1986 painting “The Last Supper (Christ 112 Times).”

“It’s how Warhol can operate on two planes at once, acknowledging industrial-level reproduction and [the] spiritual [side], which he draws from his upbringing,” she said.

Lash added, however, that one could just as easily interpret repeated images of Christ as less an affirmation of faith than as indicative of a doubt-filled search for a plausible savior. “It’s this play that works both ways. Again, allowing for faith, but also allowing for doubt and allowing for questioning.”

Warhol was -- in very Warholian fashion -- using a copy of a copy of a copy

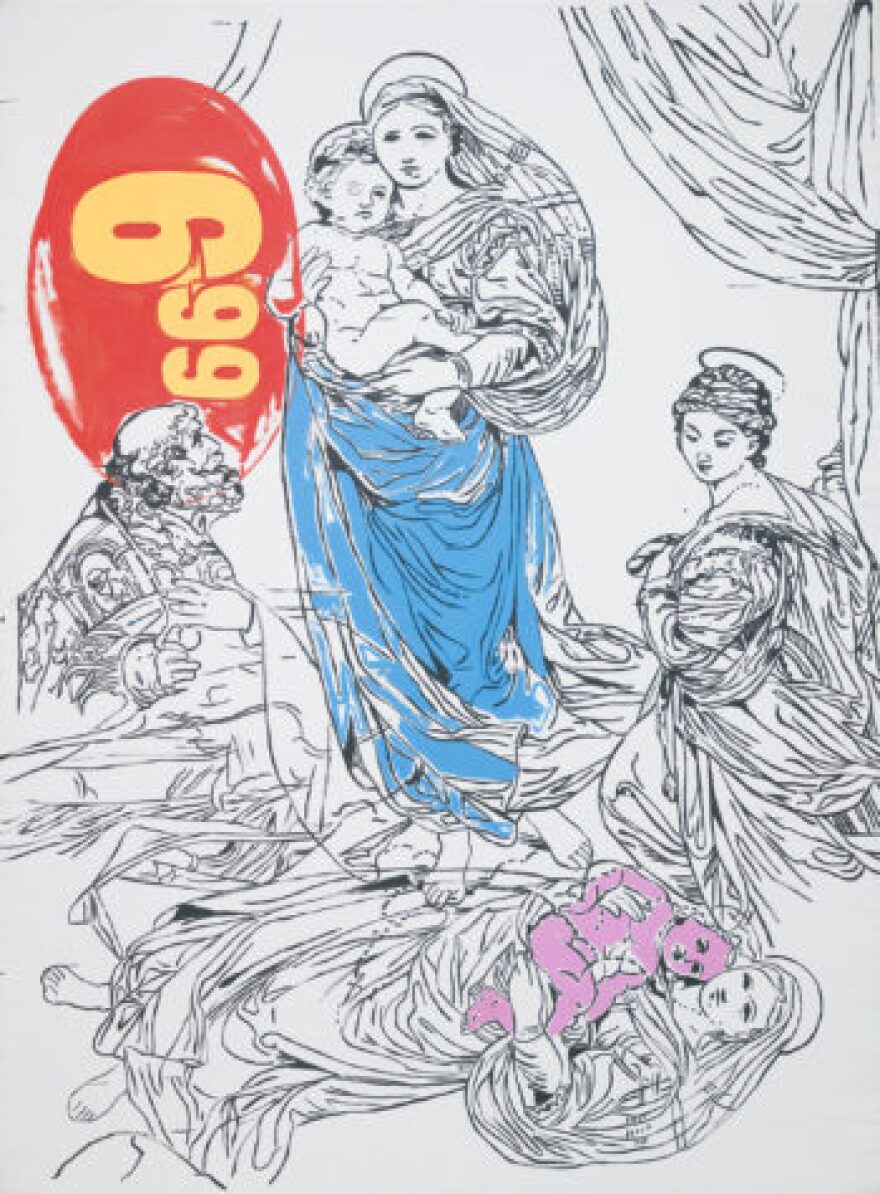

Warhol’s “Raphael Madonna - $6.99” – a 1985 take on a classic painting adorned with a bulbous red price tag – seems a particularly puckish comment on how religion is (or isn't) valued.

Warhol’s Catholicism resonated throughout his career. One of his erotic “Boy Book” sketches from the 1950s pairs a bare foot with an ornate cross. In 1967, Warhol received his one and only commission from the Catholic Church, for an artwork to be exhibited at the Vatican’s pavilion at the 1968 world’s fair, in San Antonio. The films of sunsets that he made, titled “****,” or “Four Stars,” were never shown there because the pavilion was never built. But Reel 77 is part of “Andy Warhol: Revelation.” It’s 33 minutes of gorgeous, real-time color footage of a California sunset. The soundtrack of the seldom-seen film features Velvet Underground chanteuse Nico – a denizen of his 1960s Factory scene -- reciting poetry.

“The idea of ‘let there be light,’ being this very fundamental idea for the Christian faith is something Warhol is playing with,” said University of Pittsburgh art professor Alex Taylor.

Taylor said “Sunset” too finds Warhol blurring the lines between sacred and secular.

“A sunset is the preeminent sort of kitsch image as well, and so you see Warhol moving between the two,” he said.

Perhaps the exhibit’s biggest find, though, is the true source material for the “Last Supper” paintings that were, famously, the last body of work Warhol completed before his death, in 1987. It was long thought that he was working from da Vinci’s original (or what remains of it after five centuries of restoration attempts). In fact, Diaz said, researchers learned that Warhol was – in very Warholian fashion – using a copy of a copy of a copy: a 1980s reproduction on cardboard of a 19th-century version of “The Last Supper” by the German engraver Rudolf Stang.

Warhol’s best-known “Last Supper” is a 25-foot-long, side-by-side double of the original, silkscreened in pink. It’s in the show, as are other takes on the imagery, including the painting “Be A Somebody With A Body,” which reproduces its title text alongside a ghostly outline of Christ layered over an image of a buff dude from a bodybuilding ad.

"There's elements of desire here, or queer desire."

Diaz, the curator, views the painting in light of the fact that Warhol was gay – a type of sexuality the Catholic Church still doesn’t accept.

“It really talks about the heavenly body, which is the body and blood of Christ,” he said. “But you’ve got this idea of the human body, and you’ve got this muscular figure here, so there’s elements of desire here, or queer desire.”

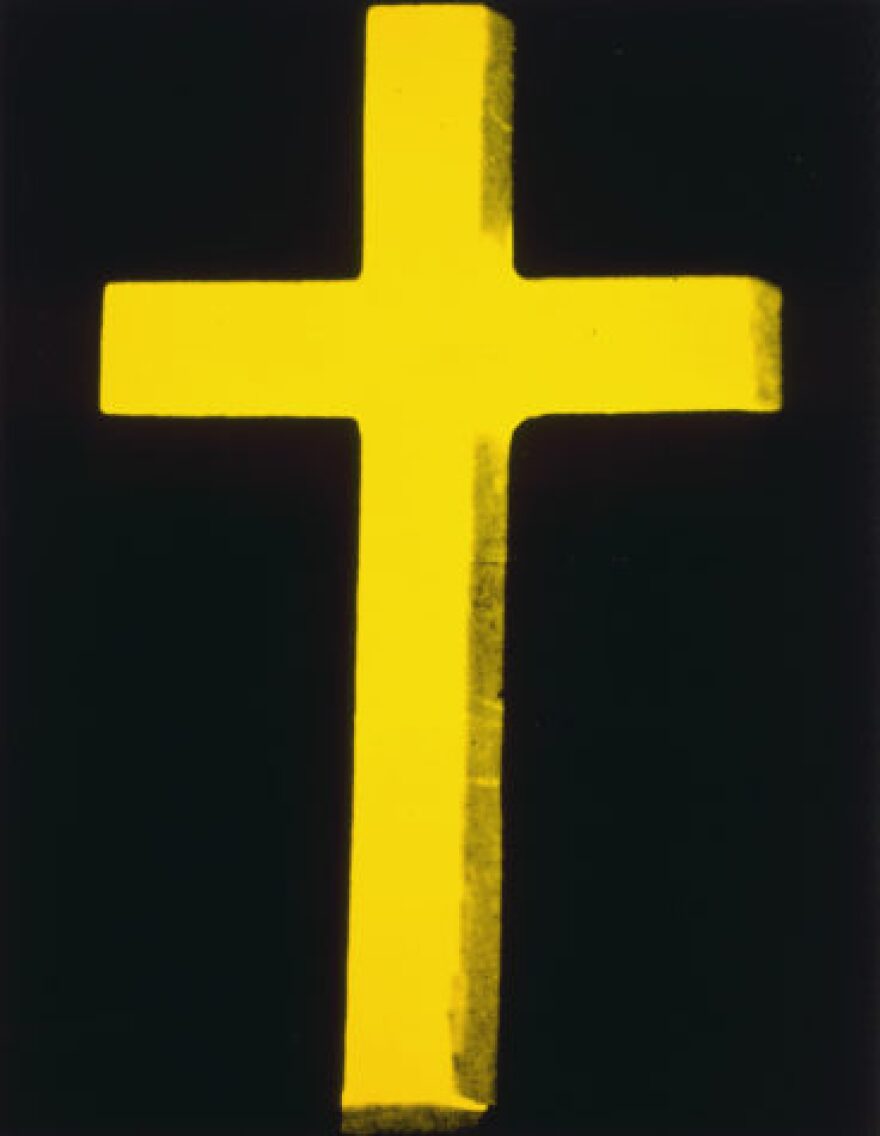

The exhibit also includes such other 1980s Warhol touchstones as his stark but somehow comforting large-scale renderings of crosses, and a series of macabre, photo-negative versions of his famous Marilyn portraits.

At the least, “Warhol: Revelation” might encourage audiences to reconsider other familiar Warhol works in a Catholic light. Some have suggested, for instance, that his famous Screen Tests – short, silent, black-and-white moving-picture close-ups of celebrities, friends and acquaintances – have something of the intimacy of the confessional about them.

But does the show bring us any closer to Warhol the person? One of his closest living relatives thinks so. Donald Warhola was Warhol’s nephew; he worked for him briefly in New York (installing the first computers in Warhol’s offices, in New York). At age 24, he was altar server at Warhol’s funeral mass, at Holy Ghost Byzantine Catholic, on Pittsburgh’s North Side. (The private service was, by design, attended by dozens, as opposed to the thousands who memorialized Warhol in New York.)

"I think it's important to show a nuanced and complex approach to his faith."

Though Catholicism was clearly part of Warhol’s psyche, he was hardly a model Catholic. Diaz said that while the artist’s diaries contain more than 50 mentions of attending mass, in later life this usually involved Warhol sitting in a back pew for five or 10 minutes at a time, and he apparently didn’t take communion or go to confession.

But Warhola says his uncle’s faith was more than skin-deep, and expressed in unpublicized acts of charity, such as regularly serving food to the homeless on Easter, Thanksgiving and Christmas at the Church of the Heavenly Rest, in New York.

If Warhol’s glamorous public image is one thing that makes it hard to see the influence of Catholicism, Warhola – who works out of the Warhol Museum as vice president of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts -- said his uncle might have nurtured the dichotomy deliberately.

“I believe that my Uncle Andy kind of created this Andy Warhol persona and it allowed him to do stuff that he might not feel comfortable doing as Andrew Warhola,” he said.

Others said we might not need to square the circle of Warhol’s faith (which Diaz notes became an issue only after Warhol’s death).

Lash wasn’t involved with organizing “Warhol: Revelation,” but she wrote an essay for the catalogue in which she cautioned against a simplistic, sacred-or-secular view of his beliefs.

The exhibit, she said, is “not making an argument that he was solely one or the other, but rather that he was both,” she said. After all, he’d hardly be the first person with a tangled relationship to religion. Just as Warhol fused high and low culture, so might he complicate our idea of devotion.

“I think it’s important to show a nuanced and complex approach to his faith, which is actually the way most people practice their faith,” she said. “There’s a lot of complexity.”

WESA receives funding from The Andy Warhol Museum.