One year ago, the Pakistani army launched a major offensive in the Swat Valley, near the border with Afghanistan. Taliban militants had seized the region and advanced into adjoining districts.

The Taliban came closer than ever before to Pakistan's heartland and the capital, Islamabad. The offensive to dislodge the militants forced more than 2 million Pakistanis from their homes.

The residents have returned, and Swat Valley is now rebuilding its shattered infrastructure and mending its frayed social fabric.

No longer banished from public view by the Taliban's strict social code, women are weaving new lives -- literally, in some cases.

With the help of the Karachi-based Heritage Foundation, widows and single mothers are learning to master looms and earn a living for the first time. With help from UNESCO, the program is offering females -- from teenage girls to women in their 70s -- the chance to learn the cherished art of Swati embroidery and make a livelihood.

Benazir Lajbar's bare feet work the pedals, and calloused fingers coax the yarn into place. The 71-year-old says her new vocation "has laid a foundation for happiness."

She adds that it is "important that these skills are continued into the next generation."

The women at the handicraft center in the town of Islampur make shawls meant to drape the shoulders of tourists who have not yet returned to this fragile valley.

A year after the army's anti-Taliban offensive, there is relative peace but not prosperity.

But life is getting livelier again.

Dancers and singers declared un-Islamic by the Taliban are free to warble their Pashtun songs and sad ballads.

Girls' Schools Reopen

Nothing more powerfully conveys the sense of a new beginning for Swat Valley than the sight of young girls on the streets hauling heavy book bags.

The Taliban destroyed or damaged hundreds of girls' schools in the area. The wanton destruction trained international attention on Swat Valley and its strategic location in Pakistan's northwest frontier region. The valley is nestled in a province called Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, near Afghanistan and Pakistan's tribal area where the Taliban and al-Qaida operate.

A year after the militants were expelled from Swat Valley, the schools they burned remain in ruins. But the girls' spirits are strong.

In the city of Charbagh, 80 girls and boys sit in a makeshift classroom fashioned from a tent. With gazes fixed on their white-haired teacher, they eagerly bellow out multiplication tables.

The large tent is one in a row of tents beside the shell of the building; their coeducational school was destroyed in 2008.

Headmaster Mohammad Tahir says this area of evergreen-covered hills suffered tremendously under the Taliban.

The children continue to pay the price as reconstruction of schools has been slow. The tents are hot during the day and mud-filled when it rains.

"We are all trying," says Tahir, who expects the children to be stuck in the tents for another year.

But the children appear unfazed by their makeshift classrooms. They evidently yearn for the routine that school offers, perhaps a measure of how disrupted their lives were made by the Taliban and then last year's military offensive.

Asked whether they are looking forward to the upcoming summer break, in unison they cry, "No!"

The U.S. Agency for International Development says that 170 schools were destroyed in Swat Valley and surrounding areas, and American funds will rebuild 108 of them through local contractors.

USAID's regional director, Ed Birgells, says his agency is establishing a hotline with Transparency International in Pakistan to ensure that the $36 million the U.S. has earmarked for Swat Valley reconstruction is not squandered.

"So that anybody that becomes aware of anything that's been going on wrong here can call this hotline, and the information ... will go directly to our inspector general," Birgells says.

Army Presence In Swat Continues

Initially Pakistan's army did the bulk of rebuilding: repairing bridges, hospitals and roads, setting up orphanages, and even constructing a showcase library in the valley's main city, Mingora.

But it has been too little. An estimated 10,000 homes, hotels and shops were destroyed by the insurgency and subsequent military offensive.

The government promises to compensate residents $4,700 for each home destroyed, and $1,800 for a damaged one -- amounts that people in Swat Valley say barely cover the cost of clearing the debris.

On a bone-crunching ride over a riverbed near Charbagh, an army vehicle steers through a pristine landscape of open skies and steep green hills. It could be a postcard of Switzerland.

An army bulldozer is busy leveling the earth in preparation for a huge park.

Maj. Asif Riaz, 32, is supervising the construction for the Pakistan army's engineering corps. He says the project is meant to soften the image of a place that had been a Taliban stronghold.

"We want to curb that tendency. So many civilized people will come here, automatically that culture, that militancy, that terrorism -- it will go off. That was the main idea," Riaz says.

The army maintains a heavy presence in Swat Valley a year after the conflict. While locals are grateful for the defeat of the Taliban, their welcome for the soldiers may be wearing thin.

'Life Is Not Back To Normal'

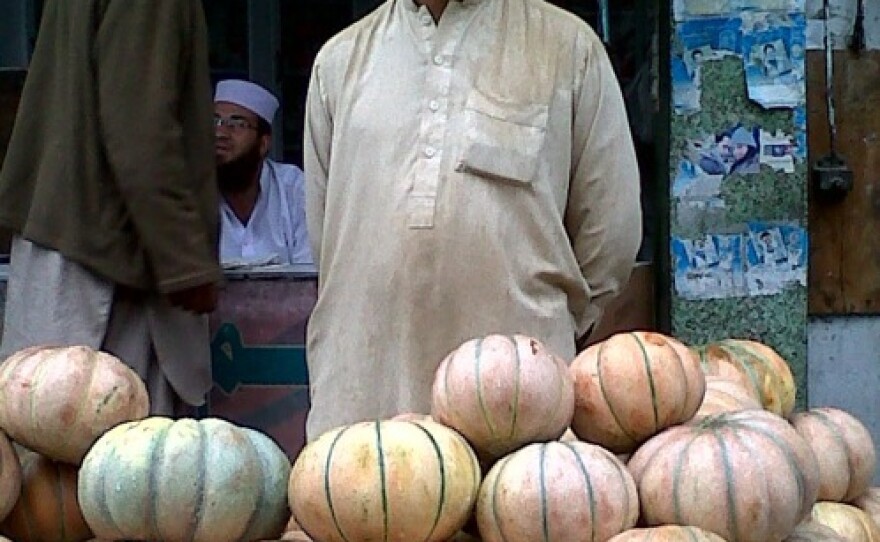

In the city center of Mingora, where vendors loudly hawk their wares and customers talk of daily life, the contrast from last year couldn't be greater. Nearly every storefront is now emblazoned with a green stenciled Pakistani flag.

Just steps from the so-called Bloody Square, where the Taliban publicly executed their victims, marketgoers complain about long lines at army security checkpoints and curfews.

"Life is not back to normal," says a 65-year-old man, Shtamand, who like many elderly Swatis uses only one name. He points to a security tag on his tunic.

"The life of the past is no more -- even in the evening we just stay indoors. They are tough with us because we are helpless," he says.

Educator and activist Ziauddin Yousafzai says the army's high profile is undermining the weak civilian government at a time when it needs strengthening.

He says the army must wind up its operation here as soon as possible.

"For their honor and for their credibility this should be their target, to contract themselves, and let the people do their job themselves. Let them have the confidence to rebuild their institutions," Yousafzai says.

But Maj. Mushtaq Khan, an army spokesman in the Swat Valley, insists the military is only filling a vacuum.

"The army is doing a lot, and they are doing it because the government has given them a duty to do it. And until and unless some funds -- which have been promised by the donor countries -- and those funds come, naturally somebody has to do it," Khan says.

The army taking a dominating role in civilian affairs arouses suspicion in Pakistan.

Mussarat Ahmedzeb, a member of the royal family who once ruled Swat Valley, says, "Peace is never with a gun."

But Ahmedzeb also says there was no option other than the army to get Swat Valley back up and running.

"Beggars can't be choosers," Ahmedzeb says. "The army is the only solution that we have."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.