A nonprofit group wants to see more unmarried women, young people and people of color on the nation's voter rolls, so it recently sent 9 million letters urging those groups to register.

But the mailers have upset some election officials, who say they've left voters confused.

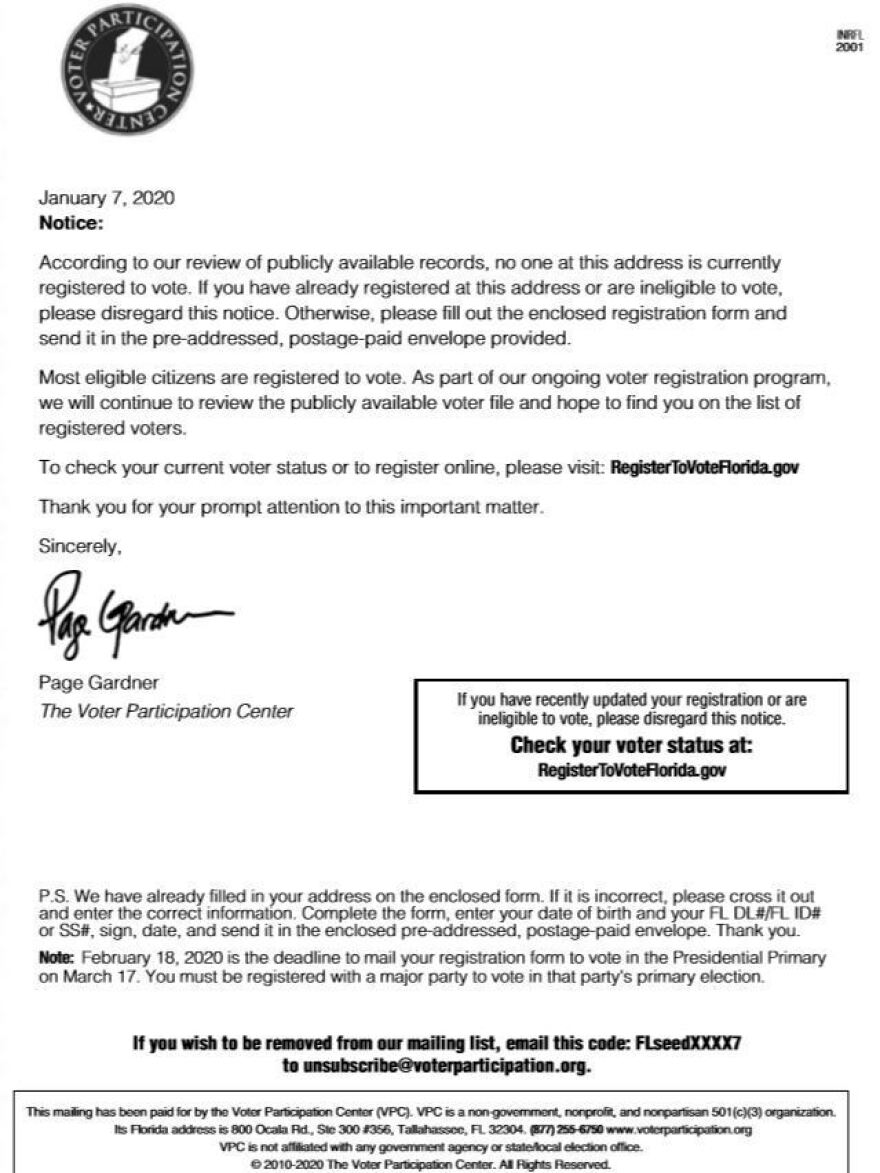

The mailers clearly state that they're from the Voter Participation Center or its sister organization, the Center for Voter Information. But the letter inside looks like it could come from the government.

It says a review of publicly available records shows that the recipient may not be registered, and if that's so, recipients should complete and send in the enclosed official registration form.

A postage-paid envelope addressed to the local election office is also included.

The problem is the mailers don't just go to unregistered voters. Sometimes, by mistake, they're sent to people who've died, are too young to vote, or are already on the rolls.

"I myself received one of the letters saying that I wasn't registered to vote," says Meagan Wolfe, the state of Wisconsin's chief election official.

Wolfe knows better than most that she is, in fact, registered — and has been for years — but she's concerned that many other voters aren't so sure.

"A lot of times we'll hear from our local election officials that they're hearing from their voters that their voters are confused," she says. "They don't know where to send those forms back. They don't know who's sending them. And one of the things that really confuses people is that they don't know why they're receiving it."

The mailings have attracted so much attention because of the sheer volume — it's probably the largest such registration drive in the country — and because it comes at a time when election officials are fighting a wave of disinformation and a decline in public confidence in elections.

"We've actually seen where it's been sent to pets," says Chris Chambliss, supervisor of elections for Clay County, Florida. He complains that this is especially troubling because some voters think the letters have come from his office, not an outside group.

"All of that snowballs because you then start getting into the conversation of 'Well if this isn't accurate, I wonder if my vote's accurate?' " Chambliss says.

Activists defend their project

Page Gardner, president of the Voter Participation Center, defends the effort and insists that errors involve only a tiny fraction of letters.

She also says her group is doing important work, registering many eligible voters who aren't registered now, especially those who tend to be underrepresented.

Gardner's group calls these voters — women, young people and people of color — part of the "rising American electorate."

"We're trying to get more and more people participating and we're trying to make sure that people know how and have the access to participating in our democracy," she says.

The campaign has been highly successful so far, registering more than 4 million voters since the effort began in 2003. The group hopes to register another million voters before November.

Its target audience tends to vote Democratic and, while the Voter Participation Center is nonpartisan, the group has liberal and Democratic ties.

Gardner acknowledges that one problem is there's no reliable list of unregistered voters in the country. So her group compiles its lists from multiple commercial and government sources and tries to screen out inaccuracies.

They even have a list of more than 3,000 names to avoid, such as "Darth Vader" and "Rip Van Winkle," and those commonly used for pets.

"Some people, when they sign up for a magazine or sign up for something, they'll use 'Fido, Fido Smith.' We don't mail to Fido," says Gardner. "What we do is use the best data available."

Despite confusion, registration

Indeed, many election officials say that the Voter Participation Center's effort is much better than similar registration drives.

It alerts election offices in advance about their mailings and works with some states to clean up their lists. Judd Choate, Colorado's election director, calls them "best in class" because if there are problems with mailings, they try to fix them.

David Becker, executive director of the nonprofit Center for Election Innovation & Research, says the campaign — and the frustrations about it — are a reflection of a sad reality in elections.

Even though many states have made registering to vote a lot easier in recent years, tens of millions of people still aren't on the rolls.

"So there's always going to be a need for some third-party registration to fill in the gaps," Becker says, adding that the challenge is doing it without turning too many people off.

Even so, Maine Secretary of State Matt Dunlap thinks the mailings do more harm than good.

"The effort itself is laudable. It's some of the mechanics I think that cause confusion," says Dunlap. "And that confusion then results in the exact opposition of what their goal is, which is to get people to participate in the process."

Dunlap wants the mailings to stop. Gardner says more are coming in April, June and September.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDEwMTk5OTQ0MDEzNDkxMDYyMDQ2MjdiMw004))