In 1963, 11-year-old Klaus Teuber received a gift that would change his life: a board game. "When I opened the box of the game, I liked the scent of the game," he remembers, inhaling deeply. "Ah, so wonderful! There is adventure in this box!"

It was a game of Romans versus Carthaginians. "It was a tabletop game with wonderful painted figures, and you had to role the dice to fight against the others," Teuber recalls.

He remembers playing it by himself, pitting one army against the other over a pretend-landscape of rivers, plains and mountains that he had fashioned at his family's home in Rai-Breitenbach, a German village located at the foot of a castle and surrounded by forest. "That was the very first step for the later development of Catan," he says.

Catan, once known as The Settlers of Catan, would become Teuber's masterpiece. It is a board game of trade and development where players compete for resources in a race to build settlements, cities and roads. The most successful developer wins.

Entrepreneurs love the game. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg is a fan. LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman reportedly has played it in job interviews to size up applicants and as a tool for making venture capital deals. In its 25th year, Catan has sold more than 32 million units, according to company figures, one of the bestselling board games of all time.

"Catan was revolutionary and its impact continues today," says Erik Arneson, author of How to Host a Game Night.

In his two decades of writing about board games, Arneson has never seen anything like Catan — a modular game where the board, made up of individual hexagons representing a range of resources from wood to sheep to brick, is different each time you play it and where the object is not obliterating your opponents, but trading with them.

"Every player is involved throughout the whole game, even when it's other players' turns, you're not sitting around waiting," says Arneson. "The games are always quite close. Nobody ever gets eliminated. It is just a remarkable achievement in game design."

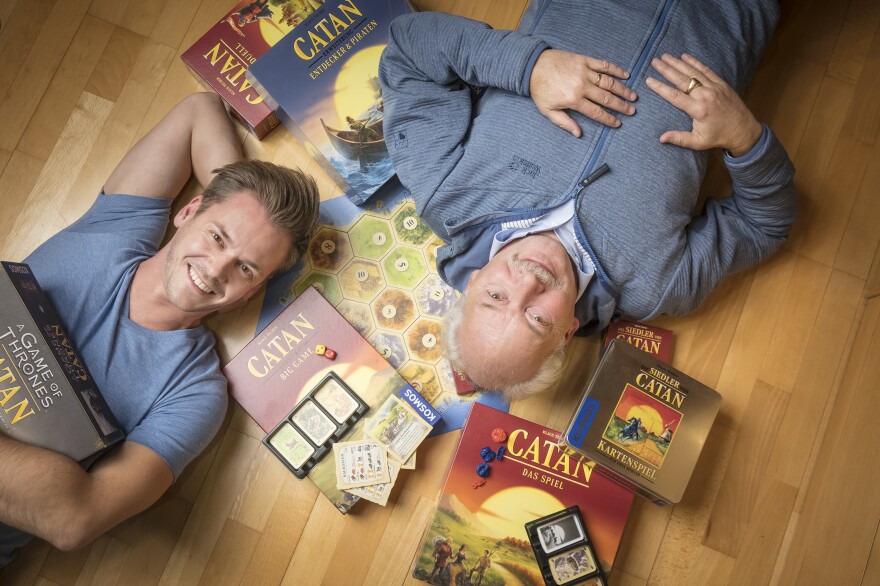

Teuber is now 68 and has just released his autobiography My Way to Catan to mark the game's 25th anniversary.

He was a dental technician who was bored out of his mind by his job when he began creating games in his basement in the 1980s. "I had a lot of frustration," Teuber says. "It was, for me, a little bit like a holiday to be at home and to develop games and, for me, to create my own worlds."

His first games did well: He won three Spiel des Jahres awards, a coveted prize in the board game industry. Then, in the early 1990s, inspired by the history of the Vikings and the Age of Discovery. "I was fascinated that they sailed the open sea and explored new lands like Iceland, Greenland or America, and in my imagination I considered what will they do when they come to Iceland? They'll need wood, they'll need to harvest food. And this gave me the idea to create a game of exploration and of settling," he says.

So Teuber began to work on Catan. The first draft "was very big," he says, and it included multiple islands and ships filled with settlers exploring new lands. It took him nearly four years to reduce the game to a single island ready to be explored and developed by players (the sea exploration segment was later sold as an expansion of the original game).

When it was released in Germany in 1995 — as Die Siedler von Catan — it was an instant hit. It also won the Spiel des Jahres. Sales didn't taper off after a few years, as with his previous award-winning games. Catan sales surged after it was released in the United States in 1996 and continued upward, prompting him to quit his day job.

Teuber has a theory about why the game became so popular. "First thing, it's variable. Every time, it's a new game. You cannot destroy someone's buildings. It's impossible," he explains. "And you have to communicate. I think these are actually factors that women like. In my opinion, part of the success is that women play together in the family with their husbands and with their children."

As families shelter in place because of the coronavirus pandemic, sales of Catan have climbed. While the global economy spirals downward, the company says sales skyrocketed by 144% for the first five months of this year.

Klaus Teuber, whose sons Benjamin and Guido work for Catan Inc., says he still plays the game with his family.

But he admits he's not very good at it and rarely wins; his son Benjamin usually prevails.

What Klaus Teuber enjoys most is the process of playing it, he says, and being there with his family — something millions of other families are apparently enjoying, too.

Esme Nicholson contributed to this story.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDEwMTk5OTQ0MDEzNDkxMDYyMDQ2MjdiMw004))