Historical fiction invites us to experience the exotic and the unknown while confirming our common humanity. I do not believe that human nature has changed much over the centuries, and it is possible to identify with the emotions, passions, and fears of men and women long dead.

But the past is also uncharted territory; it is like visiting a country where we do not speak the language. What did these people believe? What superstitions did they share? What demons did they see lurking in the dark? We want to be transported back to that foreign country, and we want the historical novelist to act as our translator.

This is what good historical fiction does, what these five novels do. The authors allow us to empathize with their characters, to care deeply about their fates. But we never forget for a moment that they are not our neighbors, not ourselves, for their expectations and ethics and boundaries are not ours. Their lives are firmly rooted in alien soil.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

A Passport To The Past: 2011's Best Historical Fiction

Elizabeth I

by Margaret George

Elizabeth Tudor was one of history's most intriguing, intelligent and enigmatic women, and Margaret George does her justice in her splendid novel, Elizabeth I, capturing the mercurial, strong-willed queen in all her neurotic brilliance. This is Elizabeth in her autumn. We are with her when she faces the greatest crisis of her reign, the threat posed by the Spanish Armada. We grieve with her over the love of her life, Robert Dudley, and feel the heat of her jealousy of her cousin, Lettice Knollys. We come to appreciate her strengths and forgive her flaws, marveling that she survived a hellish childhood and adolescence that would have broken lesser woman. So many fascinating characters flit through these pages — Dudley, Essex, Lettice, Robert Cecil, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Francis Drake, Christopher Marlowe, and Lettice's lover, perhaps the only one who can match Elizabeth's dazzling intellect, a playwright named William Shakespeare. But it is Elizabeth who charms, infuriates and mesmerizes, Elizabeth who lingers in the reader's imagination.

The Dovekeepers

by Alice Hoffman

In The Dovekeepers, Alice Hoffman tackles one of history's most tragic events. In 79 A.D., a thousand Jewish Zealots sought to defy the might of the Roman Empire from the heights of Masada, a mountain citadel in the Judean Desert. For a story so shadowed with tragedy, it is a surprisingly lyrical — even intoxicating — novel. But Hoffman's real strength lies in creating such indelible characters: the doomed women and their men who lived and loved and schemed and hoped as people have always done, even as time runs out. I cared very much for them, so much so that I dreaded what was to come. But Hoffman manages to make the inevitable tragedy bearable while still staying true to the history of Masada. This is a haunting book, both intimate and epic. I recommend it highly.

Caleb's Crossing

by Geraldine Brooks

I am astonished and chagrined that I had not read any of Geraldine Brooks' novels until Caleb's Crossing. She takes a known historical figure — Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, the first Native American to attend Harvard University — and from that single thread weaves a spellbinding tapestry depicting the world of the Puritans and the Wopanaak in 17th century Massachusetts. It is a tragic clash of cultures and gods, narrated by Bethia Mayfield, a minister's daughter who befriends Caleb. Bethia is a remarkable creation, blessed with a soaring intellect, but born into a milieu in which women were birds with clipped wings, forbidden to fly. Harvard's door was barred to her, but Caleb was offered entry, provided that he abjure his past and his blood. Caleb is an appealing character, caught between two worlds, and his fate raises thought-provoking questions about conquest, good intentions and the human spirit. This is historical fiction at its finest.

Death of Kings

by Bernard Cornwell

I am a fan of Bernard Cornwell's writing — I loved Agincourt and his Sharpe series. I was a little hesitant about his newest novel, Death of Kings — it's the sixth book in his series about Saxon England, and I hadn't yet read the other books in the series. But I was delighted to find that the book reads well as a stand-alone novel. The author works his usual magic. His characters are vividly drawn, betrayals lurk around every corner, the humor is as sharp as the swords, and the action is non-stop. I've had some experience writing battles over the years (I did 13 of them in Lionheart), and I can say with certainty that I don't think there is anyone who writes better battle scenes than Bernard Cornwell. Death of Kings comes out in the U.S. in January, and is worth waiting for.

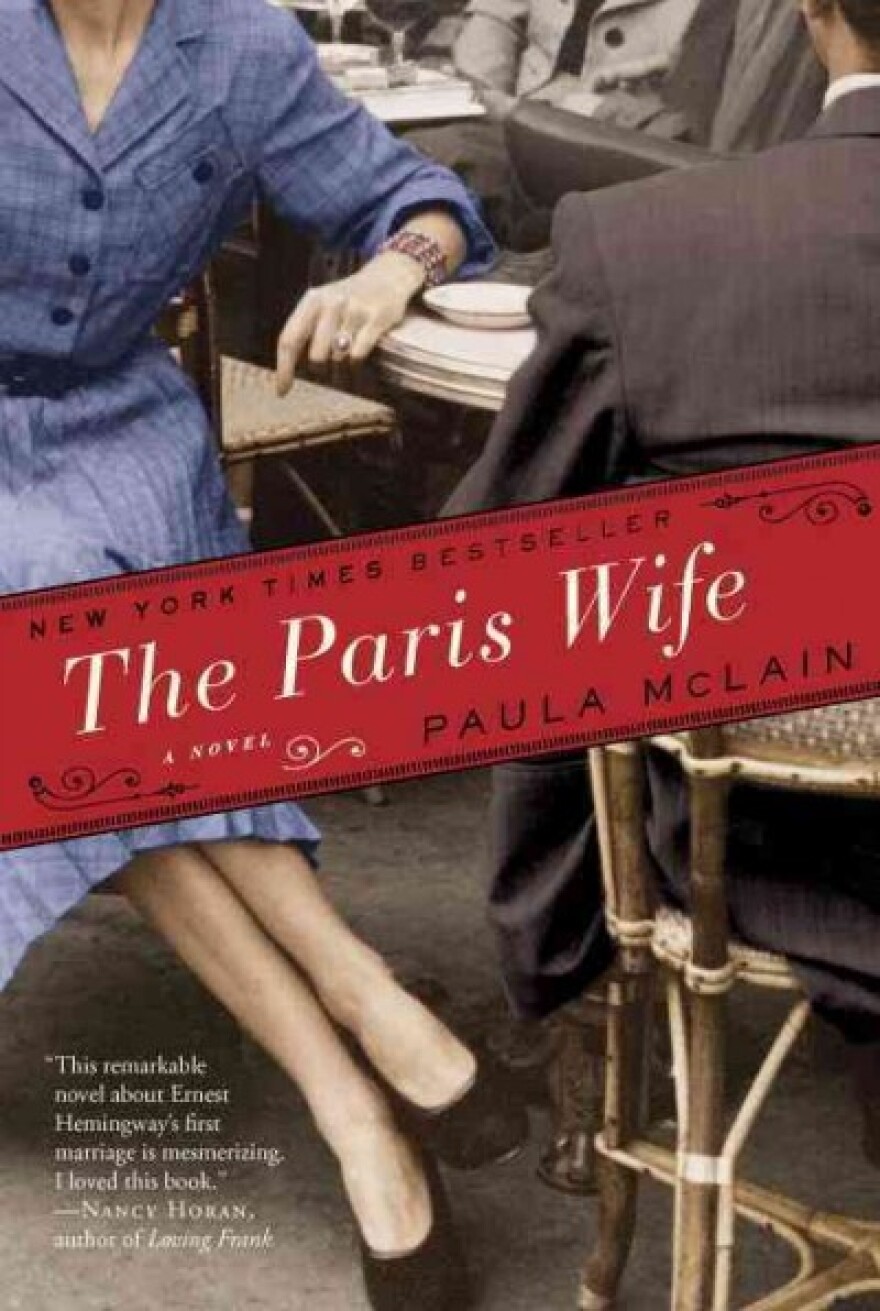

The Paris Wife

by Paula McLain

All I knew of Ernest Hemingway's first wife, Hadley, was that she lost one of his manuscripts on a train. Paula McLain's The Paris Wife reveals it was even worse than that — she actually lost everything he'd written while they were living in France. Having had the only copy of my manuscript of The Sunne in Splendour stolen from my car, I could identify with this horror story all too well, and McClain's account of the loss is not easily forgotten. The Paris Wife brings Paris in the early 1920s to vibrant life and creates a riveting portrayal of a young, fiercely ambitious writer struggling with self-doubt, poverty and traumatic memories of his WWI experiences. Their marital woes played out on the most theatrical of stages, from Paris to Pamplona; The Paris Wife is a glittering re-creation of a literary Golden Age. Readers will meet Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound. But it is Hemingway who steals the show, and Hadley who steals our sympathy.