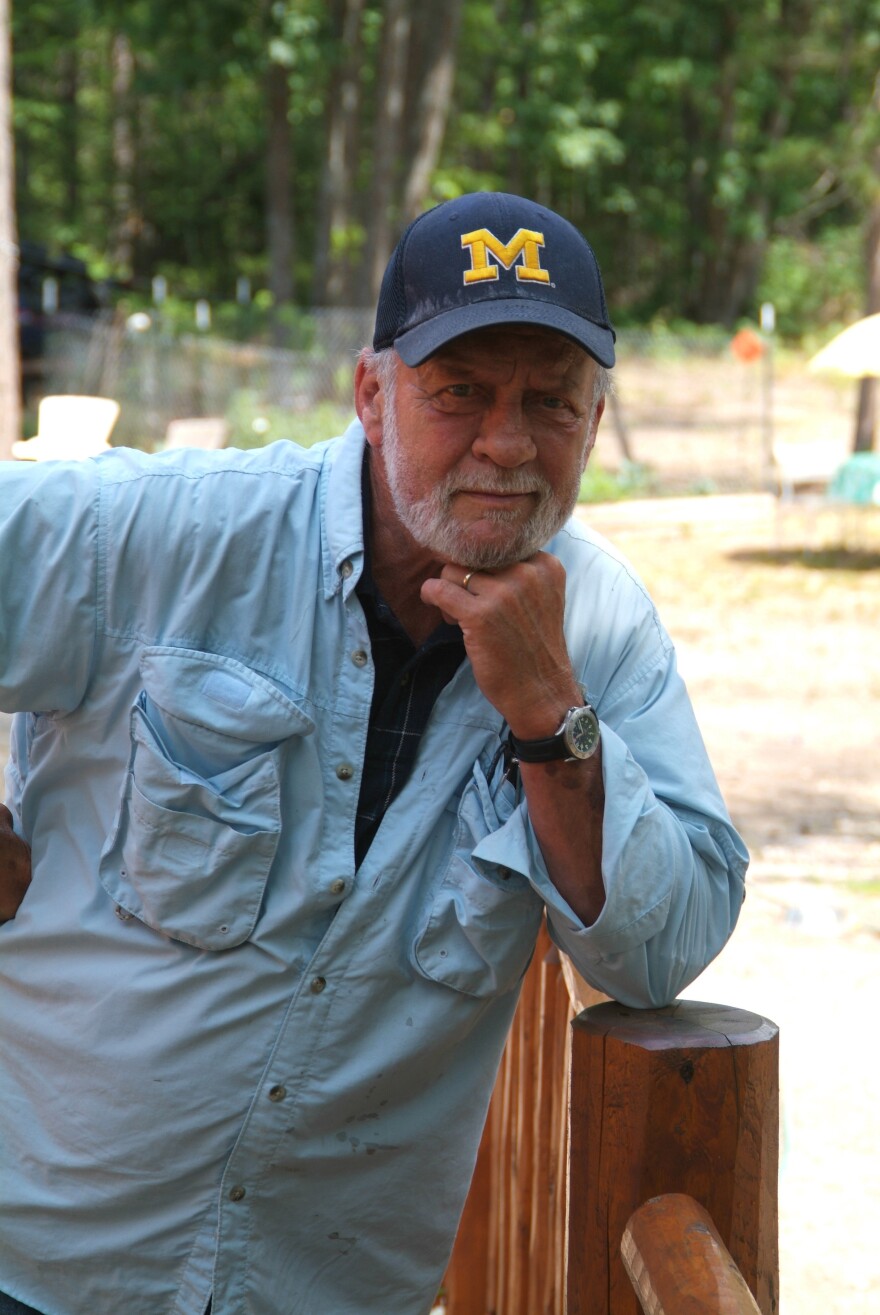

When Napoleon Chagnon first saw the isolated Yanomamo Indian tribes of the Amazon in 1964, it changed his life forever. A young anthropologist from the University of Michigan, he was starting on a journey that would last a lifetime, and take him from one of the most remote places on earth to an international controversy.

That controversy would divide his profession and impugn his reputation. Eventually he would come to redefine the nature of what it is to be human.

Chagnon's new book is called Noble Savages: My Life Among Two Dangerous Tribes — The Yanomamo and the Anthropologists." He spoke to NPR's Jacki Lyden about his time in the Amazon and what ensued.

Interview Highlights

On encountering the tribe for the first time

"When I looked up, I gasped at what I saw: a dozen of hideous-looking men with green slime running out of their noses, looking at us down the shafts of their drawn arrows. And I was startled, shocked, and the next thing that I realized I had about 20 very unpleasant dogs circling me as if I were to be their next meal."

On discovering the tribe's humor

"It became kind of a game for them to see who could dupe the dumb anthropologist more effectively than the next guy. What they did was connive with each other to invent a whole series of fake names for specific people in the village, and whenever I would check with another informant, the other informant would of course play along with the fabrication and give me the same names as the previous one did. ... I was there for six or seven months before I realized what they had done and I only realized what they had done by going to a different village, and when I reached that different village ... I mentioned cautiously the name of the head man and his wife, and they just burst out laughing because, in effect, they had told me that the names of these two people were various components of one's genitalia."

On shattering the anthropological paradigm

"One of the things that struck me was that my profession had convinced me that life in the state of nature, life among tribesmen, was very tranquil, and that's one of the first things I noticed was that they weren't living in a blissful state of nature, but in fact were actively engaged in raiding, club fighting, chest pounding. The next thing that I noticed was that most of their fights started with, or revolved around, abduction of women. ... I was shattering two rather sacred myths in anthropology. One is that natives in a state of nature are not really blissful, and two, they were fighting when they did fight over females — reproductive opportunities — and these were two rather serious challenges to the received wisdom of the anthropological times of the 1960s."

On the ensuing controversy over his theories

"There has always been a resistance in anthropology and sociology to accept biological or psychological explanations for either culture or society, and I was bucking that trend. ... The fact that endorsed what was later to be known as sociobiology, was also considered to be a defect on my part and reason to attack and discredit me."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.