Take a drive around the perimeter of Colby Frey's farm in Nevada and it's clear you're kind of on an island — an oasis of green surrounded by a big, dusty desert.

Nearby, a neighbor's farm has recently gone under. And weeds have taken over an abandoned farmhouse in the next property over.

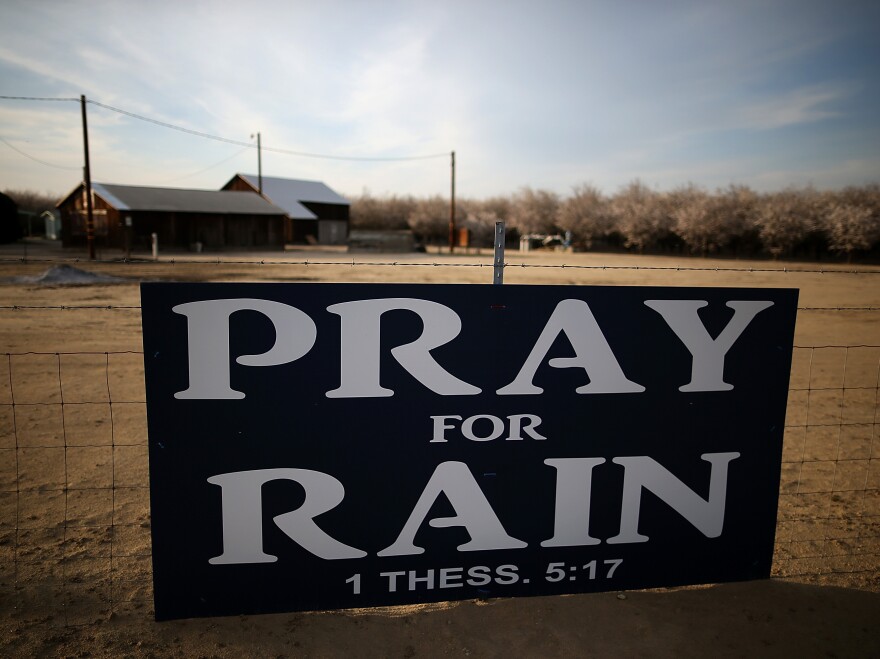

"It's just kind of sad, because it seems like it's kind of slowly creeping towards us," says Frey, a fifth-generation farmer trying to adapt to the current drought in California and in the far West.

Every farm and ranch around here is, or was, entirely dependent on water that comes from snow melt in the Sierra Nevada. So, during a different drought a few years back, the farmers got to thinking: The only way to survive was to diversify and find crops that didn't need as much water.

Sitting in what Frey calls a lab is the family's first test vineyard – an experiment inspired by the original farmhouse just across the field, which always had a grapevine next to it that yielded pounds of fruit every summer.

Unlike Frey's primary crop — alfalfa — grapes take a lot less water. "If we could only use 10 percent of the water, we could essentially take one acre of water rights and plant 10 acres of vines," he says.

And they did. And it's becoming profitable.

Frey says diversifying into a high-yield specialty crop like grapes should help them coast through a lean water year like this one.

Now, make no mistake — alfalfa is stilltheir main business. It's what northern Nevada was built on. But like other farmers in this area, the Freys are beginning to look at lower-water grain alternatives like sorghum and a desert grain from Ethiopia called teff – something that the local dairy cows seem to like.

"We've been in Nevada for a long time and if we don't adapt, then we won't survive," he says. "And there [have] been several other families that didn't make it because they didn't change the way that they did things."

Indeed, one of the unintended functions of drought is to "rejigger" the thinking about the value of water and what people do with it, says Kelly Redmond, a climatologist studying farming in Nevada's Great Basin at the federally backed Desert Research Institute in Reno, Nev.

The drought, he says, changes "how we buffer ourselves and improve our resiliency against this happening again, because there's some thought that we might see this happen a little bit more often in the future."

This latest drought has renewed questions about the viability of farming in arid places like this — especially since farmers are competing with thirsty cities for a shrinking supply of stored water.

But Redmond is an optimist.

"My sort of overall impression is [that] it will be viable, because we're clever enough to make it viable," he says.

Back at Frey's place, a team of six workers is bottling wine that's headed to stores and restaurants in nearby Reno. Frey says he's hoping to show some of his skeptical neighbors that grapes can be a profitable side business.

But he says he can't blame some families for shutting down and selling off their land, especially in devastating years like this. He's thought of it, too.

"We'd probably make five times more money," Frey says. "We wouldn't have to worry about the water or the droughts or anything like that, and we could live the rest of our lives."

"But that's not what we want to do," he adds.

After all, farming is what his family does. His great-great-grandfather was one of this state's first farmers, and Frey plans on handing the farm over to his kids one day.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDEwMTk5OTQ0MDEzNDkxMDYyMDQ2MjdiMw004))