We’ve heard a lot about lead service lines after the Flint water crisis and Pittsburgh’s efforts to replace its old pipes. But that’s not the only way lead can get into your drinking water.

The faucets and fittings and solder on the pipes inside your house can also contain lead.

After January 2014, the rules changed for plumbing products that are meant for drinking water. Now, the wetted surfaces of pipes, faucets and fittings can’t have more than 0.25 percent lead.

If you have older faucets in your home, experts say it’s a good idea to swap them out.

But it’s not always easy to find the right products at the hardware store, because the labels are confusing.

Elin Betanzo met up with me at a hardware store near her house. She directs the safe drinking water program with the Northeast-Midwest Institute.

“You have to pick up each package and examine it. Is it lead free? Is it third party certified?” she says.

We’re in the plumbing section in front of a bunch of faucets and valves and fittings.

“So I’m seeing these two packages side by side for these faucet connectors,” says Betanzo. “One is marked clearly on the front of the package: lead free. But there’s no third party certification on that package. Right next to it, there is a package for the same product that has the third party certification listed but no marking that says that it is lead free.”

So, she says, if you buy the one that doesn’t have any symbols on it from groups that certify a product as lead free, you’re trusting the company.

Betanzo grabs a box with a faucet in it and turns it around to read the fine print.

“In very fine print, it says this product contains less than 0.25% weighted average lead content on wetted surfaces,” she points out.

And that’s the case for a lot of these packages. You have to look for the tiny print that says it meets the standard, and different companies use different wording.

To make things more complicated, Betanzo says you also have to watch for little stickers that say a product is not intended for drinking water. She picks up a little package with a bright yellow sticker on it.

“So here is an angle valve that says it’s for ice maker installation but has a sticker on the front that says it’s not for potable water. This was a recommendation from the EPA if a hardware store had old stock that met the old definition of lead free that they could continue to sell them if they’re marked ‘not for potable water,’” she says.

That old definition of “lead free” was enacted in 1986. Back then, plumbing products were allowed to have up to 8% lead in them.

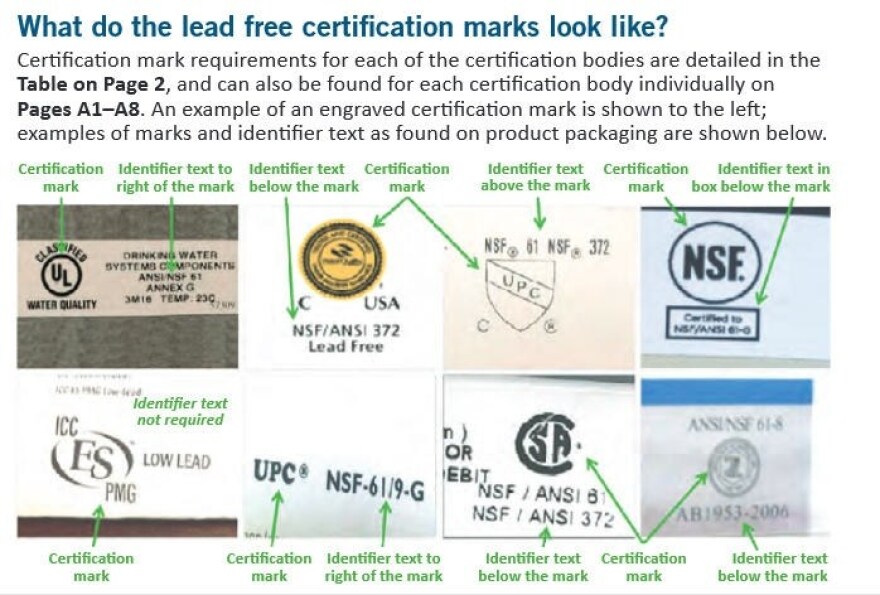

It’s so confusing that the EPA has issued an 11 page document to help consumers interpret the third-party certification symbols on plumbing packaging. In the document, the EPA says a product that doesn’t have a certification symbol could still meet the standard, but the agency recommends calling the manufacturer to check.

Here’s the EPA’s explanation of how to decipher the symbols from the eight different groups that can do third-party certification:

Elin Betanzo says when you go to the store now, you should look for that language on the packaging describing “0.25 percent weighted average lead content” and a third-party certification symbol with NSF 61 or NSF 372 near it.

The EPA says it wants to clear up some of this confusion. It’s proposed that all “lead free” products be labeled in some way. And marked directly on the product itself, not just the package.

The agency just finished up its public comment period. It could take a couple of years to finalize the new rules – so keep reading those labels.

Both the EPA and the industry trade group Plumbing Manufacturers International declined our interview requests.

###

This story comes from our partners at Michigan Radio's Environment Report, a program exploring the relationship between the natural world and the everyday lives of people in Michigan.

Find this report and others on the site of our partner, Allegheny Front.