Updated at 10:08 p.m. ET

Senators fought a genteel melee over new witnesses in the impeachment trial on Wednesday but even hours' worth of questions, answers, and litigation on other issues didn't reveal an obvious path forward.

Members used dozens of written submissions over several hours to argue for and against the case for witnesses, the strength of the impeachment case and, in some cases, to actually ask questions.

But as the Q&A session rolled on Wednesday ahead of another session scheduled for Thursday, the way ahead still was not clear as to whether John Bolton or other witnesses might appear.

"At this point it's obvious — we don't have the votes yet," said Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C., talking to reporters during a break.

The issue about Bolton's testimony isn't only important to the substance of the evidence in the case, but how much longer the trial goes.

If the Senate were to reject the admission of Bolton or other witnesses in a vote expected on Friday, it could close down the proceedings comparatively quickly — quickly in Senate terms at least.

If the chamber admits Bolton, that could add days, weeks or more.

Ambassador Bolton

Although Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., is understood to have told senators that he can't marshal enough support to block witnesses and simply end the trial, it also isn't clear whether, if senators voted to admit new witnesses, they could then agree on which ones or the rules under which they could testify.

The White House has warned senators that it might resist an attempt to call former national security adviser John Bolton or other administration officials and that could result in months of legal gridlock that would idle the Senate.

"We're going to be here for a very, very long time and that's not good for the United States," warned lawyer Jay Sekulow.

President Trump's attorneys also argue that the Senate shouldn't be a fact-finding body in the impeachment process and that it must deal with the evidence only developed so far by the House.

Bolton himself also presents special issues, lawyer Patrick Philbin argued on Wednesday, because his role might be protected most strongly by the doctrine of executive privilege, which permits an administration to shield some of its workings from the public.

"National security and foreign affairs are the crown jewels of executive privilege," Philbin said. "To suggest of the national security adviser, 'Oh, we'll just subpoena him, he'll come in, it'll be easy' — that's not the way it would work."

Philbin also confirmed that the White House has notified Bolton that the manuscript he has submitted for pre-publication review contains what it considers top secret information and accordingly can't be published until it's been cleared.

That raises the stakes for Bolton to appear himself, or for senators to get access to the manuscript — if they can reach some kind of accommodation among themselves.

House impeachment manager Rep. Adam Schiff, D-Calif., warned Senators that he believed the White House is trying to stonewall them the way he argues it already has the House.

Resolving issues over witnesses needn't take unduly long, he said, among other reasons because senators already have U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts presiding over the proceedings. Schiff said he trusts Roberts to adjudicate questions of witnesses and process — and quickly.

The bottom line, Schiff said, is to bring all relevant evidence into the process to make it legitimate.

"You can't have a fair trial without witnesses," he said.

Questions to the desk

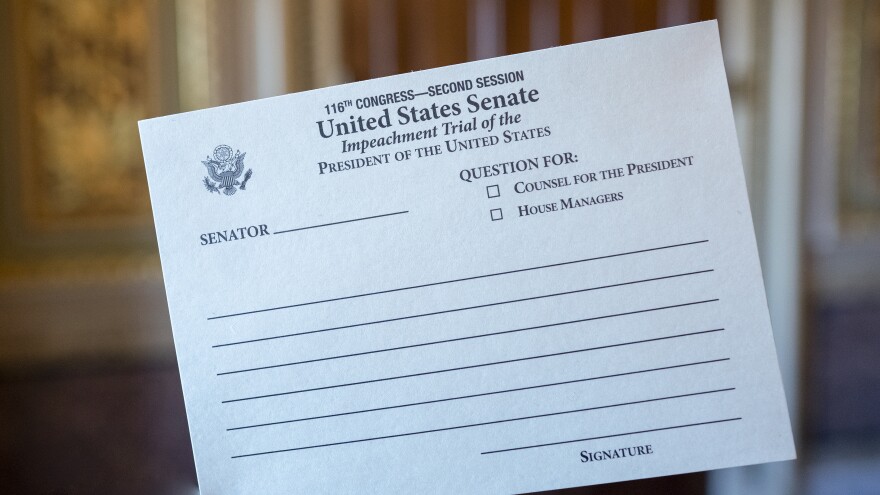

Senators wrote questions on specially printed cards that were then carried to Roberts, who read them either for the House Democrats or Trump's lawyers.

Senators used their questions to set up partisan allies to deliver talking points, ask questions of opponents that might embarrass them, and, occasionally, to try to elicit new information.

Ears across Washington perked up each time Republicans Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska or Mitt Romney of Utah were associated with a query; they're among the small group of potential rebels who might join with Democrats to vote to add witnesses.

Four such Republicans would be required. Although the descriptions about McConnell's remarks to senators this week suggested he may have a sense about which ones have reached that decision, their identities weren't certain.

One thing that was resolved by events on Wednesday was that Colorado Sen. Cory Gardner would not vote for new witnesses, his office said. Arizona Sen. Martha McSally later joined him with a statement on Twitter.

I have heard enough. It is time to vote.

— Martha McSally (@MarthaMcSally) January 30, 2020

Otherwise much of the discussion in the Senate chamber involved lobbing parliamentary brickbats, with the odd philosophical digression about the nature of presidential power.

The professor

Another of Trump's attorneys, Alan Dershowitz, for example, argued that because a president always believes his own election and administration are in the public interest, it's virtually impossible for him to act officially without also acting for his own personal benefit — except in cases when he might profit financially.

And that means he can't be impeached on the basis of motives that no outside person could parse, he argued.

"It cannot be a corrupt motive if you have a mixed motive that partially involves the national interest," Dershowitz said.

Democratic senators rejected that notion in questions that set the stage for Schiff to repeat his criticisms of Trump's broad claims of power under the Constitution.

"What you see is a president who identifies the state as being himself," Schiff said.

Another Democratic manager rejected the idea, raised in a question, that Trump circumvented any wrongdoing because the military assistance he froze for Ukraine last year ultimately was released and allowed to flow as Congress intended.

No, said Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif. — first because the Government Accountability Office has since concluded that freeze broke the law but also because, under Democrats' "attempted extortion" metaphor, Trump still had abused his power.

"Getting caught doesn't mitigate the wrongdoing," Lofgren said.

The Biden impeachment

Other questions focused on the Constitutional standards for impeachable conduct, the president's power to conduct foreign policy and what standard of evidence should apply in the trial.

Many of Democrats' questions emphasized witnesses and actions by Trump.

Meanwhile, many Republicans' questions underscored what they called the weakness of the process so far and also included reminders about the role of Vice President Joe Biden in the Ukraine saga.

Trump sought investigations by Ukraine's president including one into Biden and his son Hunter, who was paid by a Ukrainian gas company at the same time Biden was leading Ukraine policy for the administration of President Obama.

Former Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi, who gave a presentation about the Bidens earlier in the trial, reprised what she called the troubling story and used, as Trump's camp had promised before, the impeachment of Trump as an impeachment of Biden.

Other subsequent questions afforded openings later in the evening for Trump's team to revive the subject of Biden and what his attorneys suggested might be wrongdoing during the Obama era.

No official inquiry has "cleared" the Bidens or "debunked" the allegations they might have acted improperly, argued Trump attorney Eric Herschmann.

House manager Rep. Val Demings, D-Fla., urged senators to confine their discussion in the chamber to what she called the heart of the matter.

"As we go through this very tough, very difficult debate over whether to impeach and remove the president of the United States I'd ask that we stay focused," she said. "The last few days we've seen many distractions, many things have been said to take our minds off the truth of why we're really here."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDEwMTk5OTQ0MDEzNDkxMDYyMDQ2MjdiMw004))