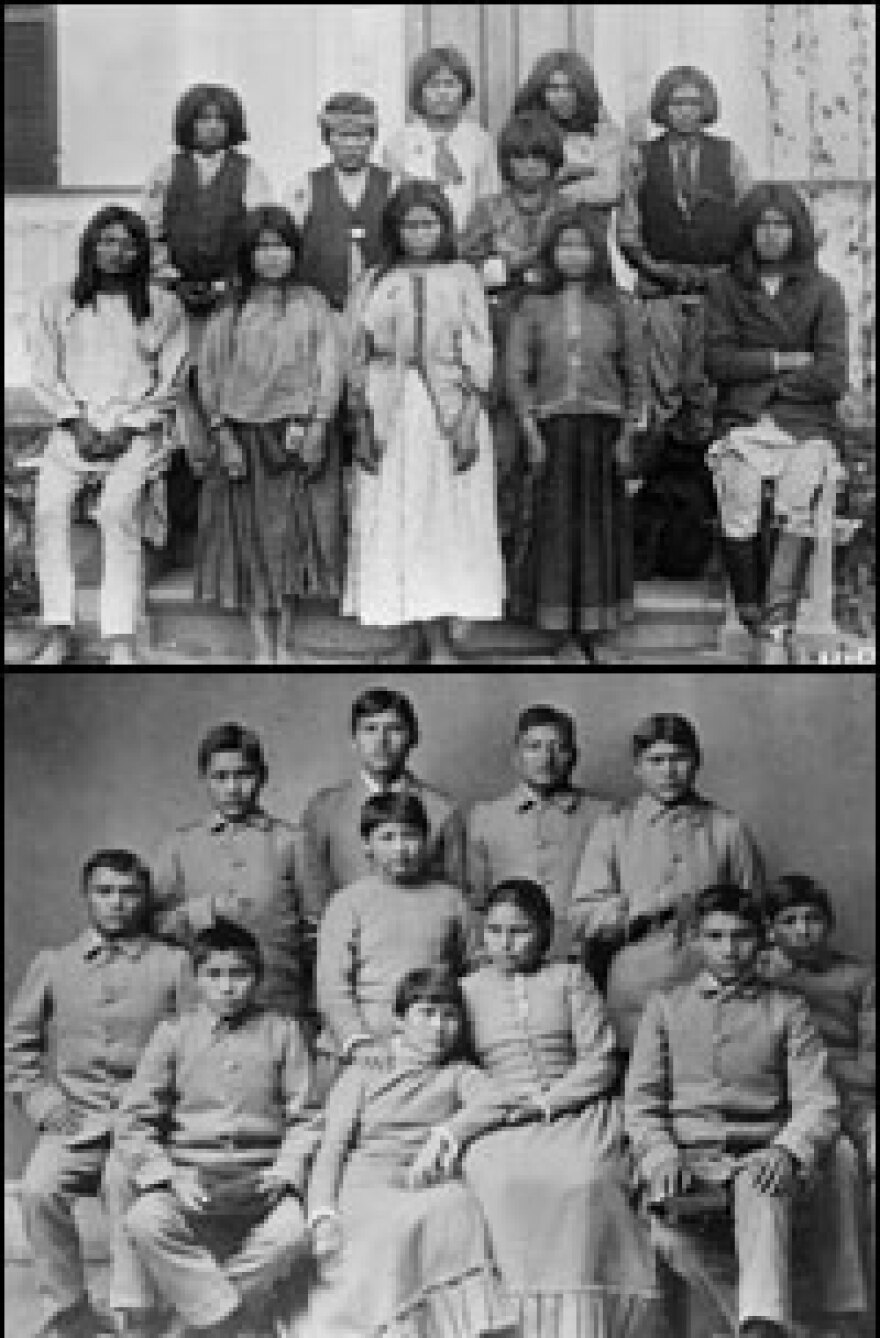

For the government, it was a possible solution to the so-called Indian problem. For the tens of thousands of Indians who went to boarding schools, it's largely remembered as a time of abuse and desecration of culture.

The government still operates a handful of off-reservation boarding schools, but funding is in decline. Now many American Indians are fighting to keep the schools open.

'Kill the Indian ... Save the Man'

The late performer and Indian activist Floyd Red Crow Westerman was haunted by his memories of boarding school. As a child, he left his reservation in South Dakota for the Wahpeton Indian Boarding School in North Dakota. Sixty years later, he still remembers watching his mother through the window as he left.

At first, he thought he was on the bus because his mother didn't want him anymore. But then he noticed she was crying.

"It was hurting her, too. It was hurting me to see that," Westerman says. "I'll never forget. All the mothers were crying."

Westerman spent the rest of his childhood in boarding schools far from his family and his Dakota tribe.

He went on to become an actor, an activist with the American Indian Movement and a songwriter.

He sang about his experiences growing up: "You put me in your boarding school, made me learn your white man rule, be a fool."

The federal government began sending American Indians to off-reservation boarding schools in the 1870s, when the United States was still at war with Indians.

An Army officer, Richard Pratt, founded the first of these schools. He based it on an education program he had developed in an Indian prison. He described his philosophy in a speech he gave in 1892.

"A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one," Pratt said. "In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead. Kill the Indian in him, and save the man."

Transforming People, Inside and Out

Fifty years later, Pratt's philosophy was still common.

In 1945, Bill Wright, a Pattwin Indian, was sent to the Stewart Indian School in Nevada. He was just 6 years old. Wright remembers matrons bathing him in kerosene and shaving his head. Students at federal boarding schools were forbidden to express their culture — everything from wearing long hair to speaking even a single Indian word. Wright said he lost not only his language, but also his American Indian name.

"I remember coming home and my grandma asked me to talk Indian to her and I said, 'Grandma, I don't understand you,' " Wright says. "She said, 'Then who are you?' "

Wright says he told her his name was Billy. " 'Your name's not Billy. Your name's 'TAH-rruhm,' " she told him. "And I went, 'That's not what they told me.' "

According to Tsianina Lomawaima, head of the American Indian Studies program at the University of Arizona, the intent was to completely transform people, inside and out.

"Language, religion, family structure, economics, the way you make a living, the way you express emotion, everything," says Lomawaima.

Lomawaima says from the start, the government's objective was to "erase and replace" Indian culture, part of a larger strategy to conquer Indians.

"They very specifically targeted Native nations that were the most recently hostile," Lomawaima says. "There was a very conscious effort to recruit the children of leaders, and this was also explicit, essentially to hold those children hostage. The idea was it would be much easier to keep those communities pacified with their children held in a school somewhere far away."

Discipline and Punishment

The government operated as many as 100 boarding schools for American Indians, both on and off reservations. Children were sometimes taken forcibly, by armed police. Lomawaima says that's not the only reason families let their children go.

"For many communities, for a variety of reasons, federal school was the only option," she says. "Public schools were closed to Indians because of racism."

At boarding schools, the curriculum focused mostly on trades, such as carpentry for boys and housekeeping for girls.

"It wasn't really about education," says Lucy Toledo, a Navajo who went to Sherman Institute in the 1950s. Toledo says students didn't learn basic concepts in math or English, such as parts of speech or grammar.

She also remembers some unsettling free-time activities.

"Saturday night we had a movie," says Toledo. "Do you know what the movie was about? Cowboys and Indians. Cowboys and Indians. Here we're getting all our people killed, and that's the kind of stuff they showed us."

And for decades, there were reports that students in the boarding schools were abused. Children were beaten, malnourished and forced to do heavy labor. In the 1960s, a congressional report found that many teachers still saw their role as civilizing American Indian students, not educating them. The report said the schools still had a "major emphasis on discipline and punishment."

Wright remembers an adviser hitting a student.

"Busted his head open and blood got all over," Wright recalls. "I had to take him to the hospital, and they told me to tell them he ran into the wall and I better not tell them what really happened."

Wright says he still has nightmares from the severe discipline. He worries that he and other former students have inadvertently re-created that harsh environment within their own families.

"You grow up with discipline, but when you grow up and you have families, then what happens? If you're my daughter and you leave your dress out, I'll knock you through that wall. Why? Because I'm taught discipline," Wright said.

Sherman Indian High School

Not all American Indians had negative experiences at boarding schools. Some have fond memories of meeting spouses and making lifelong friends. But scathing government reports led to the closure of most of the boarding schools.

One school that remains is Sherman Indian High School in Riverside, Calif. — the same boarding school Toledo attended.

Hershel Martinez, a Navajo student, gathers with a group of friends in a school hallway to form a drum circle. The school encourages cultural activities like this. That's one reason Martinez feels more comfortable here than at his former public school in Los Angeles.

"Everyone was wondering what nationality, what race am I," Martinez said when asked about being at a public school. "I'd tell them and they're like, 'Wow, you're Indian. You're like the only guy I know who's Native.' But here, at Sherman, they know how I feel about being Native. And they understand where we're all coming from."

But this year, the federal government made a budgeting change that reduces funding to the off-reservation boarding schools. And their future is in doubt.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.