So you're at a company shindig, talking to a group of colleagues over hors d'oeuvres, when the background music finally becomes too grating to pass by without comment. "They should just put on some real jazz," your co-worker says. "Like Coltrane."

Because he claims to like jazz, he may well be insufferable. But you aren't trying to get on his bad side, and in any event, you don't have anything against reportedly good music. So, forcing enthusiasm, you assent heartily.

Yet your strategy backfires: You've only invited further interrogation. "Really?" he asks. "What are your favorite Coltrane records?"

With the late legend's Sept. 23 birthday imminent, it's even more likely that you could be caught sleeping on the iconic saxophonist's enormous discography. So here's a bluffer's primer to John Coltrane, such that you can comfortably (perhaps even honestly) respond to your interlocutor with the only socially appropriate answer to his question:

"Man, I have so many. They're all so great."

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Get To Know John Coltrane

Moment's Notice

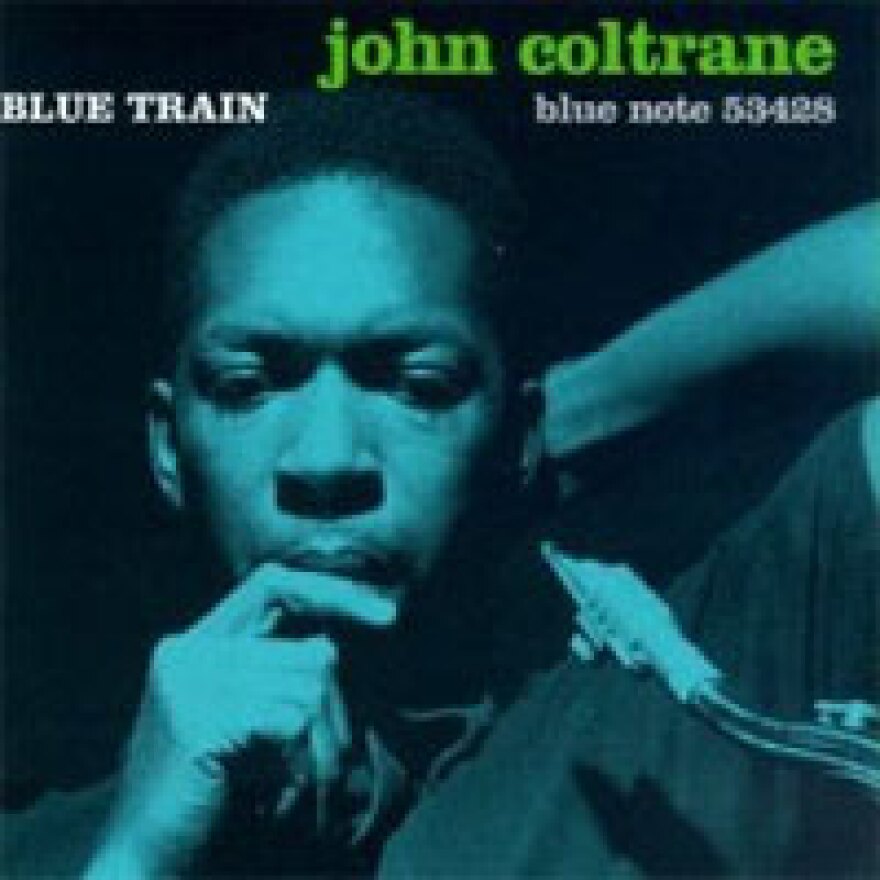

From 'Blue Train [Expanded Edition]'

By John Coltrane

The John Coltrane with whom most fans are familiar — the muscling, hard-charging ubermensch of a saxophonist — emerged in the public spotlight around 1955, when Miles Davis invited him into his quintet. The breakthrough led to his own deal with Prestige Records, which was recording Davis at the time. But the record from this period that shines brightest in the canon was actually a 1957 one-off for Blue Note, whose proprietors heartily encouraged rehearsals, multiple takes and other forms of studio perfection. "Moment's Notice" is a standout of Blue Train — it's one of Coltrane's many attractive tunes based on a set of difficult chord changes he developed himself. "Coltrane himself even called Blue Train one of his favorite albums," you can say with smug self-satisfaction.

Naima

From 'Giant Steps'

By John Coltrane

If you get to talking about the 1959 masterpiece that is Giant Steps, a convenient narrative can help you look smart. Here's your thesis: Giant Steps was both a peak and the beginning of a transition in John Coltrane's career. The "career highlight" part is easy: In the fast tunes, it's like an angry Minotaur rampaging through a labyrinth he designed himself; in the slower ones, the beauty may overwhelm you. But it also marked the end of an era for Coltrane. It was clearly the apotheosis to his hyperkinetic bebop-on-growth-hormones concept ("sheets of sound," it's been called); within a year, he'd leave Miles Davis in search of a different direction with his own working group. Having impressed your conversation partner, try to demonstrate a similarly passionate appreciation for "Naima" — easily Coltrane's most famous ballad. It should be obvious why.

My Favorite Things

From 'My Favorite Things'

By John Coltrane

Though Coltrane's many admirers may disagree on matters of taste, they all acknowledge that the constant creative transformation which defined his career is practically inconceivable. Be sure to adopt this front, if only because it's true. As evidence, try "My Favorite Things," from the 1960 album of the same name. You'll notice that 1) he's playing the soprano sax; and 2) the entire piece has more or less one bass note to it. Many suspect that Coltrane got such ideas from listening to the drones and open modes of Indian music, while critics have pointed out that he used to talk music with Ravi Shankar. Whatever the case, it's a massive shift in approach from Giant Steps, recorded hardly a year prior to this. By flipping a sugary little waltz from The Sound of Music into a brooding meditation, Coltrane created a vehicle he would use for the rest of his career, even as he drastically changed the way he played it.

A Love Supreme, Pt. 1: Acknowledgement

From 'A Love Supreme'

By John Coltrane

Many great Coltrane LPs were made in the '60s; they're so wonderful that Morning Edition commentator Ashley Kahn wrote a whole book about Impulse, Coltrane's record label through much of the decade. But A Love Supreme (from late 1964) is guaranteed to come up in conversations about Coltrane; it's so important that Kahn wrote a separate book on this one album alone. Ambition abounds here: The record is a paean to God in the form of a four-movement suite, recorded by Coltrane's most heralded band (the "classic quartet," with pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones). Give the two-disc deluxe edition a fair shake: Literally within four notes of this first movement, you'll hear a phrase which jazz musicians have adopted as a motto for their art. Should you not have time for that, you can always launch into laudatory panegyrics: You can't lose credibility by praising this record among mixed company. Just go back and have a listen. You shouldn't need to convince yourself that what you said was valid.

Mars

From 'Interstellar Space'

By John Coltrane

If you've made it this far, then you've probably been able to save face. But you can score extra brownie points by jawing about late-period Coltrane, guaranteed to elicit an opinion from any supposed jazz-head. Toward the end of his career, Coltrane fully embraced free improvisation, seeking more direct self-expression. Hence the debate: Did he go crazy, or did he merely erupt in spasms of uncontrollable genius on a nightly basis? Make your own judgments, but — just sayin' now — the cool kids all lean toward the latter. As with the best abstract art, it generates its own logic. In "Mars," which opens the 1967 duet LP with mercilessly active drummer Rashied Ali, initial confusion may well give way to trance-like enthrallment after a few close listens. Notice that what substitutes for a theme sounds remarkably similar to Coltrane solos of Giant Steps vintage, just re-constructed as motives that repeat, build, become unstable, morph and reiterate ad infinitum. As for the virile barbarity of it all, it's proper to embrace it — it is, after all, the best part.