We don't know too much about a Nepalese man who's in medical isolation in Texas while being treated for extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis, or XDR-TB, the most difficult-to-treat kind. Health authorities are keen to protect his privacy.

But we do know that he traveled through 13 countries — from South Asia to somewhere in the Persian Gulf to Latin America — before he entered the U.S. illegally from Mexico in late November. He traveled by plane, bus, boat, car and on foot.

And all the way he may have unwittingly put hundreds of other people at risk of getting the highly drug-resistant TB strain.

That possibility has triggered a far-reaching investigation by the U.S. and other health authorities to track down potentially exposed people around the world. "It's a huge effort that's ongoing," Dr. Martin Cetron, who heads the division of global management and quarantine at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, tells Shots.

The case, first described by Betsy McKay at the The Wall Street Journal, provides a window on a problem that health officials say is sure to arise more and more often.

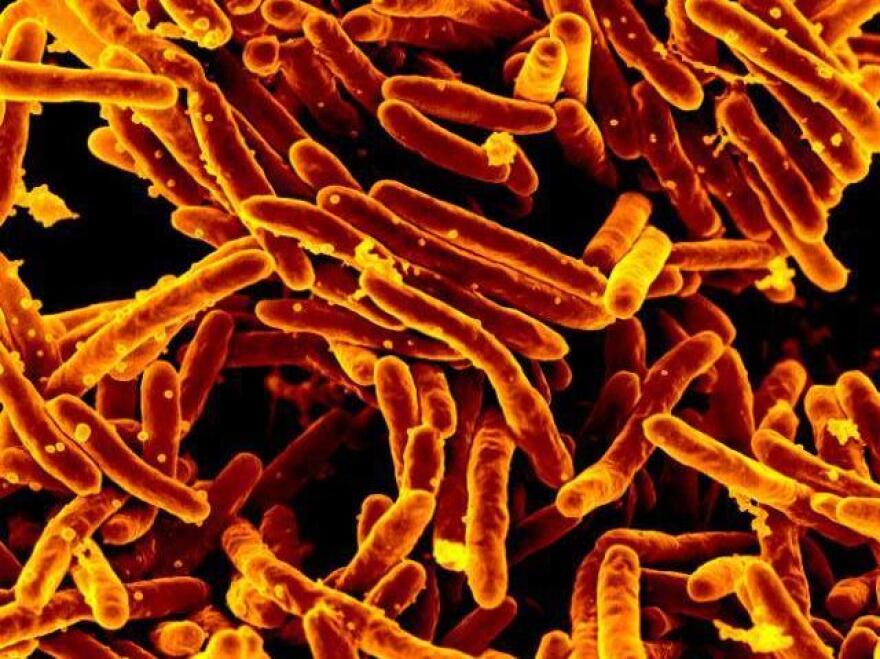

XDR-TB is a more dangerous part of a bigger problem with multi-drug-resistant tuberculosis, or MDR-TB.

"We estimate at any one time in the world there are about 630,000 cases of MDR-TB," Dr. Dennis Falzon of the World Health Organization tells Shots, referring to multi-drug-resistant TB. MDR-TB isn't vanquished by the two mainstay drugs isoniazid and rifampin and requires more complicated drug regimens.

In 2007, a young lawyer named Andrew Speaker became the best-known case of MDR-TB when he flew to Europe, potentially exposing other passengers.

XDR-TB is resistant not only to isoniazid and rifampin but also a class of drugs called fluoroquinolones and one or more potent injectable antibiotics. TB germs become drug-resistant when patients fail to complete a course of treatment. When a partly-resistant strain is treated with the wrong drugs, it can become extensively resistant.

There are about 60,000 people with XDR-TB strains like the Nepalese man who's in isolation, Falzon says.

That means there are other people with XDR-TB traveling the world at any given time. Like the Nepalese man, until he got to the U.S., Falzon says, "many of these XDR cases aren't even diagnosed."

To give some idea of the public health challenge, such cases present, Dr. Kenneth Castro of the CDC's division of TB elimination tells Shots that over 700 people were thought to be exposed to the Nepalese man while he was in the custody of the U.S. Border Patrol.

"Out of those, 60 percent or so are back in their country of citizenship which then leaves many others that are being sorted through to determine if (their exposure) was real or not," Castro says.

But at least those potential contacts were known. Falzon says it's almost impossible to trace people who may have had close contact with the man during his complicated itinerary.

"We cannot trace down a bus tour which happened within, let's say, the space of a few weeks," Falzon says. "And it's very difficult to get details. The person (in detention) doesn't speak English."

The long-haul flight he took from a country on the Persian Gulf to Brazil, which exposed fellow travelers sitting within a couple of rows of his seat, occurred months ago. "We're trying to track down the exact details of that flight and the persons who were exposed," the WHO official says.

TB is spread through droplets in the air released by coughing or sneezing. It requires close and prolonged exposure, so a shorter flight, for instance, is not thought to pose a danger.

Castro says there's no reason to think XDR-TB is more contagious than less-resistant or drug-susceptible strains. "The alarm bells have to do with the consequences of the disease," he says — that is, the two-year, toxic, costly drug regimen necessary to cure the infection.

One big advantage these days, Castro says, is a lab test that can tell within two days whether a patient's sputum contains TB bacilli with mutations that confer resistance to seven different drugs.

"This is a game-changer," Castro says. The TB organism is notoriously slow-growing, so it used to take six weeks to culture it in laboratory dishes and test its susceptibility to different drugs. "The result is that some folks died before results of drug susceptibility tests came back," he says.

The CDC has recorded 63 cases of XDR-TB from 1993 through 2011 (the most recent data available), more than half of them among foreign-born people.

When illegal immigrants with drug-resistant TB are isolated in ICE detention facilities, things get complicated. They cannot be deported until they're no longer contagious, which can require months of complex treatment. Otherwise, they'd pose a risk to fellow travelers.

But Dr. Edward Zuroweste of the nonprofit group says just because such patients are no longer contagious doesn't mean they're cured. This requires at least two more years of treatment — often back in a home country without specialists in treating drug-resistant TB or access to the proper drugs.

Zuroweste's group has a contract with ICE to make sure deportees have appropriate treatment. It checks up on them regularly to see if they're sticking with it. He says 84 percent complete treatment, and the rest either disappear or refuse further treatment.

He says the U.S. and other nations should expect to see growing numbers of these difficult cases. "There's no way to ever isolate the U.S. from an airborne disease," Zuroweste tells Shots. "The world is becoming much smaller and people travel a lot. So what we have to do is attack the disease, not the individual unfortunate enough to contract the disease."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDEwMTk5OTQ0MDEzNDkxMDYyMDQ2MjdiMw004))