When it comes to diversity, children's books are sorely lacking; instead of presenting a representative range of faces, they're overwhelmingly white. How bad is the disconnect? A report by the Cooperative Children's Book Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison found that only 3 percent of children's books are by or about Latinos — even though nearly a quarter of all public school children today are Latino.

When kids are presented with bookshelves that unbalanced, parents can have a powerful influence. Take 8-year-old Havana Machado, who likes Dr. Seuss and Diary of a Wimpy Kid. At her mothers' insistence, Havana also has lots of books featuring strong Latinas, like Josefina and Marisol from the American Girl Dollbooks. She says she likes these characters because, with their long, dark hair and olive skin, they look a lot like her.

Havana's mother, Melinda Machado, grew up in San Antonio, and her family is from Cuba and Mexico. She says she didn't see Latino characters in books when she was a little girl, so she makes sure her daughter does.

"But you do have to look," she explains. "I think children today are told, 'You can be anything.' But if they don't see themselves in the story, I think, as they get older, they're going to question, 'Can I really?' "

Only a small fraction of children's books have main characters that are Latino or Native American or black or Asian. And it's been that way for a very long time. In 1965, The Saturday Review ran an article with the headline "The All-White World of Children's Books" — and the topic is still talked about today, nearly 50 years later.

Do White-centric Books Sell Better?

So why is diversity in children's books such a persistent issue? One theory is that it's all about money. "I think there is a lot of concern and fear that multicultural literature is not going to sell enough to sustain a company," says Megan Schliesman, a librarian with the Cooperative Children's Book Center.

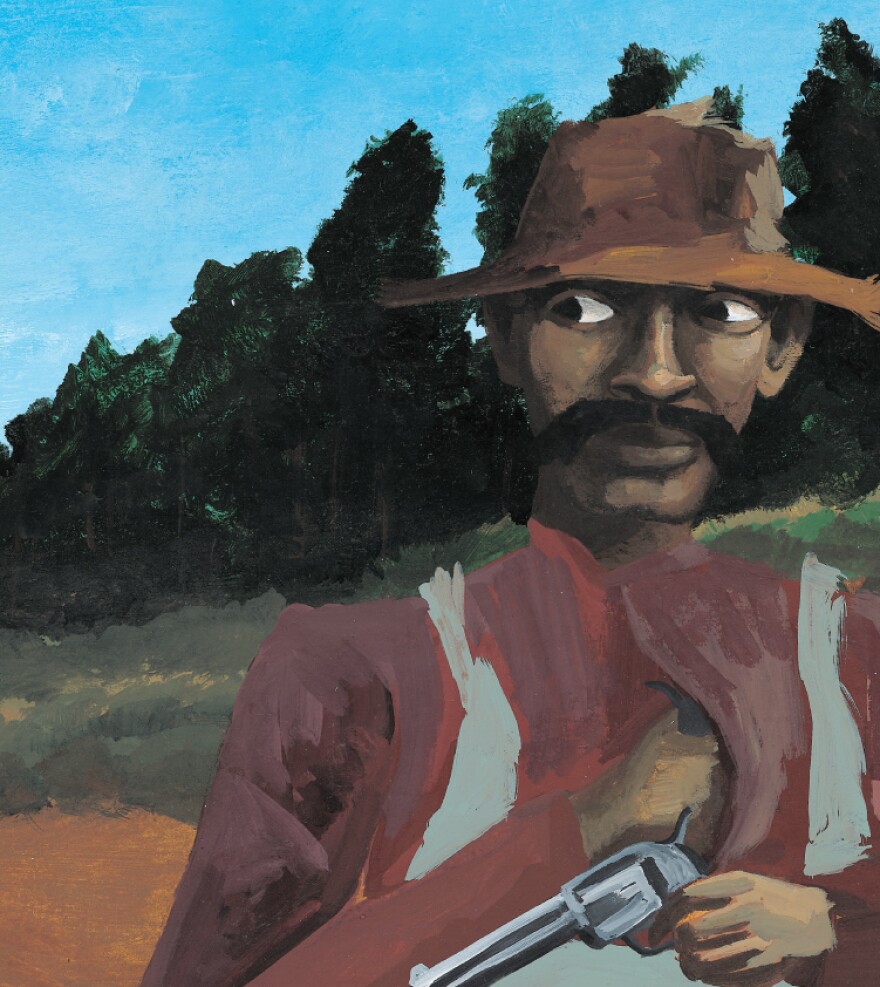

But Schliesman says that belief is a myth — after all, some companies publish multicultural children's books and are profitable. For instance, Lerner Books published the nonfiction picture book Bad News for Outlaws: The Remarkable Life of Bass Reeves, Deputy U.S. Marshal. The book, which told the story of a black lawman in the Old West, won awards, got attention from libraries and independent bookstores and became a best-seller for the company.

"There is an enormous amount of demand for this kind of content from libraries," says Andrew Karre, an editor with Lerner Books. According to Karre, public and school librarians try very hard to put books with a wide range of characters on their shelves.

But while librarians are influential, they can't make a book sell. "There are something like 6,000 public libraries in the country," Karre says, "And even if they buy five copies of the book for their collection ... that's not going to crack those best-seller lists of any kind, really."

Why Diverse Book Options Matter

Vaunda Micheaux Nelson wrote Bad News For Outlaws, as well as several other books about African-Americans. She is also a librarian at the public library in Rio Rancho, N.M. She says that young people need to see themselves represented on the page so that they will continue reading.

"If they don't see that then perhaps they lose interest," Nelson says. "They don't think there's anything in books about them or for them."

Nelson adds that it is also important for white children to see characters of different races. "Not only do they learn to appreciate the differences," she explains, "but I think they learn to see the sameness, and so those other cultures are less seen as 'others.' "

Nelson says she understands that publishers are going to respond to what the market demands. Right now, the vast majority of best-selling children's books are by and about white people. But as the U.S. population changes, Melinda Machado thinks the books American children read will change, too.

"I think eventually the demographics and the economic power will catch up," Machado says. "Will it catch up, you know, while my daughter's still a child? Probably not."

Publishers might want to catch up a lot sooner, though. According to new data from the Census Bureau, nearly half of today's children under 5 years old are non-white.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org. 9(MDEwMTk5OTQ0MDEzNDkxMDYyMDQ2MjdiMw004))