I had never heard a voice like Marcia Reifman's before — androgynous, earthy, slow and poised. Full of mystery. But she didn't always sound like this.

The day we met in 2020, we were seated next to each other at a Photo Club gathering at the Vista Grande Public Library in Santa Fe, N.M., just a few months after I moved there from my hometown of Miami, Fla.

I was 23 at the time and she was 74, but it felt like she was of my generation, not just in appearance — she sported all-black Chuck Taylor All Stars and her hair was braided in colorful ties — but also in spirit and energy. I knew within minutes of being in Marcia's presence — of hearing her voice — that I wanted to make photographs with her.

Marcia agreed and suggested that I call her one day — not to talk, but to listen to her voicemail. I eventually rang her and waited until I heard a voice on the other line. It was clear, bright and reassuring — in some ways, totally opposite of the one I'd heard in the library. I was stunned.

She later told me the reason for the disconnect: In 2013, Marcia was diagnosed with stage 4 squamous cell carcinoma and underwent a 13-hour surgery in which she had more than three-quarters of her tongue removed. The procedure was followed up by 66 radiation treatments administered daily with concurrent chemotherapy.

The most agonizing part of it all, she says, was the treatment and recovery — the energy she had withered away, along with what she calls her "life force."

As our friendship deepened, Marcia and I began to speak in vulnerable ways we hadn't before.

It felt odd at first, feeling myself becoming such close friends with someone who was the same age as my grandparents, and Marcia tells me it was just as strange for her. We started to question and explore who we were to one another and who we were to ourselves.

Prior to moving to Santa Fe, I spent three years committed to Contact, a photo series in which I created rituals with my family and used them to reexamine the significance of death in the wake of my mother's passing. I had visions of continuing this exploration in a desert landscape, but I found myself changing — my preoccupation with death was morphing into an obsession for life.

I was finding my rhythm again and building my own family in Santa Fe, and Marcia was a big part of that. Together, we were streamlining our personal narratives into a shared record of indignation, healing, growth and victory. I wanted a space to visualize this in. I wanted a home. So Marcia and I constructed an outdoor structure on the land behind her house and called it the Refuge.

It took nine months of planning and building — and the help of our friends Aaron, Russell, Osiel and Alicia — to create the desert studio that eventually became the home for this photo project, TRIALS.

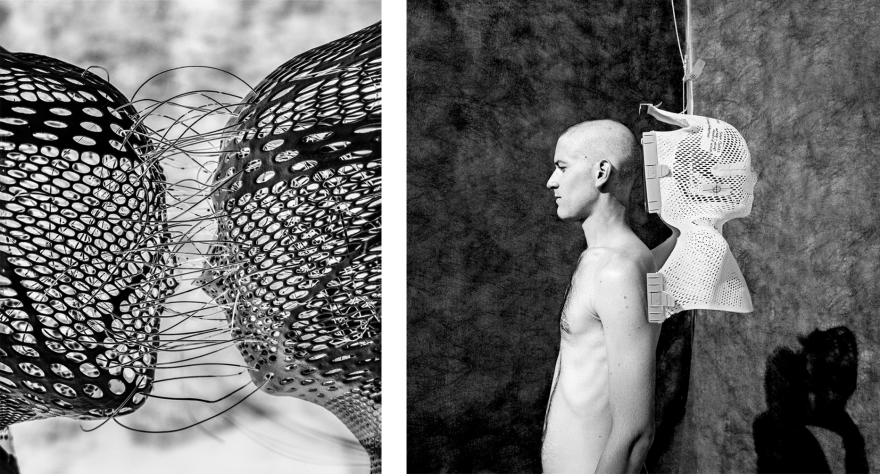

The structure lends itself to a very haptic experience. Because of zoning restrictions, it can't be a permanent installation, so it needs to be reassembled each time it's used. We determine the size and shape with each new build, creating a different environment every time.

In the Refuge, secrets and movements are shared, photographs are made and recorded. When I set out to capture myself within it, I compose the image, move and interact with the installation, and ask Marcia to hit the shutter when I'm at my peak. I do my best to feel myself in that moment. I want to reveal something.

Marcia tells me that I met her right at the time. And though her life force is not nearly what it once was, she describes our friendship as a jolt that woke her up after six years of feeling totally dead.

In a way, we act as counselors or therapists for each other. In talking to her, I've come to acknowledge and confront my inner walls, discovering access to what lies behind them — my personal truth — along the way. When I feel like I've lost the keys that grant me that access, I trust Marcia to help me find them again.

Though I may not be able to provide her with the emotional support she's provided me, I think that I am able to help Marcia in a tactile way — her diagnosis put a pause on her own artistic practice, but the intensity and passion of our collaboration has led her to revive her creative pursuits.

Marcia has been an artist since she was a little kid. She holds an MFA in Photography, an M.Ed. in Art Education, and is the retired department chair of Media Arts at Santa Fe Community College.

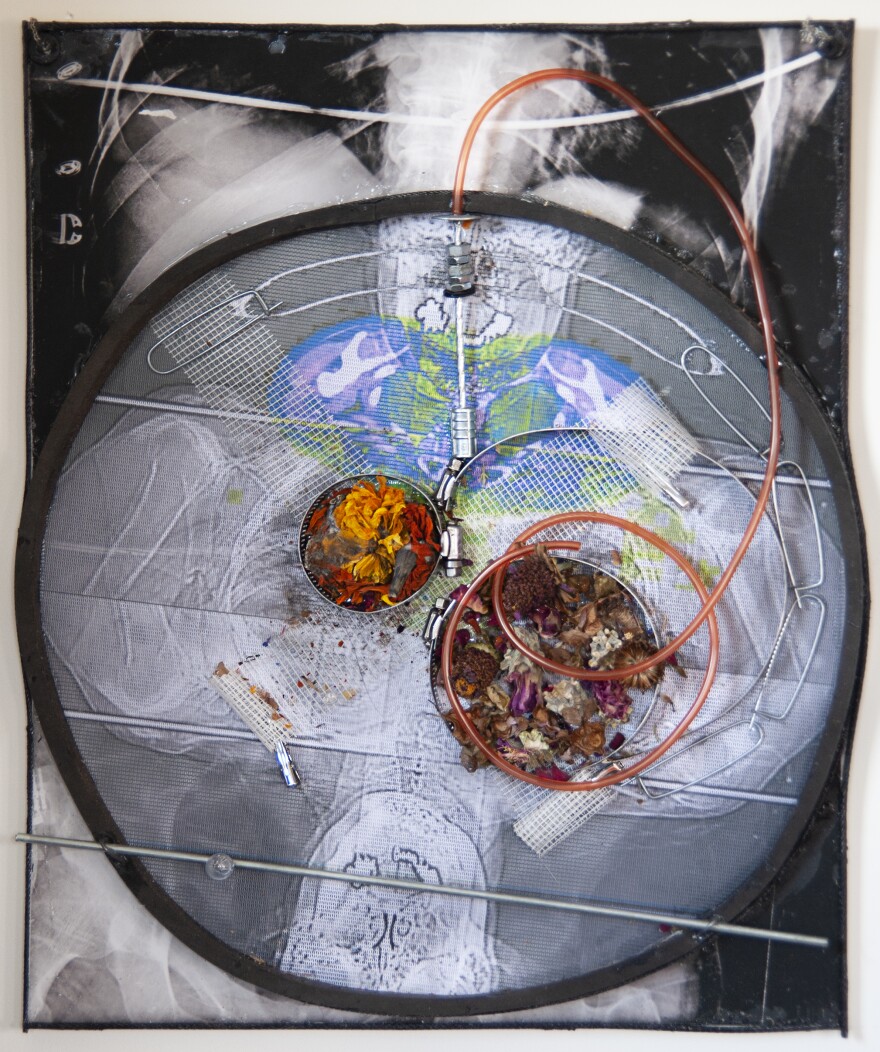

She is currently working on a series of 66 multimedia pieces that represent her 66 days of cancer treatments. Each image is composed of found material and her PET scan imagery.

She says this new body of work represents how her cancer treatment felt — "metallic, indifferent, poisonous, relentless and deadly."

When I asked her how she picks these materials, she answered, "osmosis."

"It's very direct," she told me. "I'm influenced by what's around me, especially when I'm working with you in the Refuge. The way you use wire and how you connect with materials ... there is an absorption that happens to you that I really relate to, and that transfers itself into action and excitement, and that translates into me creating."

Seeing her make new work after so many years of not doing so has been such an inspiring process to witness.

Struggle and pain are integral to existence, or what I call, being up against myself. These photographs I've made with Marcia embody human existence and the experiences associated with it — suffering and mortal fear, relief and ordeal, directness and brutality, a liberation with no winners.

TRIALS aims to encapsulate those frictions of reality, wounds from survivors, and the ambiguity of human conflict. In other words, it's about acknowledging ourselves as living memorials, people becoming testimonies to events that happened but are no longer there.

For as long as our paths continue to cross, the Refuge will be a home to me and Marcia — and others who feel inspired to embark on their own creative journeys.

You can find more of Andrés Mario de Varona's work at AndresMario.com or @andres.deva on Instagram.

You can reach Marcia Reifman at mreifman@q.com.

Tsering Bista photo edited this story.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.