The traditional narrative goes like this: After World War II, upper and middle class white families fled the inner cities for the suburbs. They were chasing the "American Dream" of white picket fences, two car garages and shopping centers you could drive to. The children of those Baby Boomers grew up, fought back and now, are moving back to the cities.

According to a new report from the Urban Land Institute's Terwilliger Center for Housing, the first part of that story is more true than the second part — so far.

While cities may be seeing a comeback, suburbs still have a significant advantage. "Housing in the Evolving American Suburb" looked at the 50 largest metro regions in the country, and found that 79 percent of the population lives in the suburbs. Since 2000, suburbs have accounted for 91 percent of the population growth.

And as for that idea that Millenials are moving into the city? Three-quarters of people age 25 to 34 live in the suburbs.

Redefining the suburb

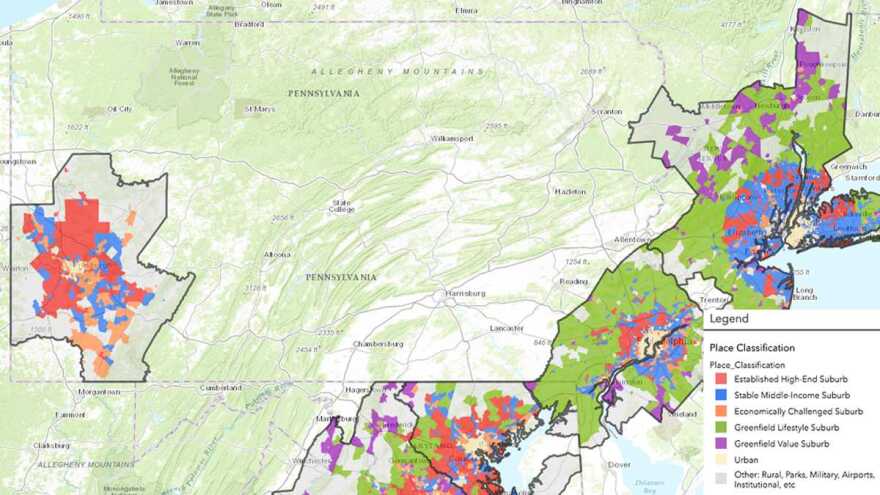

Understanding why suburbs still have such a hold on population and growth requires looking at the definition of a suburb. ULI defined five different types of suburbs, from "established high-end suburbs" to "economically challenged suburbs." They also mapped those suburb varieties — check out Pittsburgh and Philadelphia's burbs.

"There is no single thing that can be called a 'suburb,'" said ULI Terwilliger Center for Housing Executive Director Stockton Williams. "Understanding those differences matters, so we can break down generalizations that too often stop the conversation."

These shades of gray can help explain why suburbs are still holding strong despite recent interest in urban living. Even as some young people move into cities, other groups are just arriving in the suburbs.

In the 50 largest metro regions, 76 percent of the minority population lives in suburbs. Williams says a lot of this is driven by young immigrant families for whom the suburbs are "the preferred destination." Many of them are settling outside cities, attracted to the reasonable cost of home ownership, accessibility of green space and better schools.

On the flip side, many low-income urban residents are being pushed into the suburbs against their wishes. In many cases, an influx of people interested in urban living causes rents and home prices to rise. Long-time urban core residents often end up in suburbs, further from services and public transportation.

And redefining the rivalry

But this positive growth for suburbs doesn't mean cities are destined for another five decades of hollowing out.

"There's this idea we have that if cities are winning, suburbs must be losing. Or if suburbs are strong, cities must be weak," said Williams. "In fact, many of the cities that are doing well, we're also seeing their suburban areas doing well."

There was a time when suburbs were gaining at the expense of cities, but Williams thinks that metro regions are much more intertwined now than they were before.

"Think of the sort of cliche story of a young professional moving to the urban core and renting an apartment," said Williams. "Then, they're getting a little older and looking to own a home, they find that it's more affordable further out. Maybe when they're in their middle age, they'll move back closer in. You need a healthy, diverse city and suburban housing market to support that."

Cities risk falling into the trap of isolating themselves from the suburbs that support them, says Williams. The report found that certain types of suburbs are working to become more appealing to young people and city dwellers, just as cities are doing the same for suburbanites. This balancing act could create more varied, diverse regions.

The report looked at 2000 to 2015, so the much-touted "urban revival" may not be reflected in the results yet. Fifteen years down the road, cities may have regained some of that population growth from their suburban neighbors. Williams hopes that it's collaborative growth, rather than competitive.

Find this report and others at the site of our partner, Keystone Crossroads.