Margaret Wroblewski's daily commute on the Metro often comes with an unwanted consequence, and it's not necessarily unexpected delays or crowded trains. It's sexual harassment.

Like many students, the 22-year-old relies on the Metro rail system to get around the Washington, D.C., region every day. She's studying photojournalism at George Washington University and commutes from her home in Maryland.

Wroblewski posted her latest encounter with sexual harassment on Snapchat last fall. As her friends weighed in, she quickly realized she wasn't alone.

"That really just fueled my fire that something really needed to be done about this issue, because I think it needs to be brought to light," Wroblewski says.

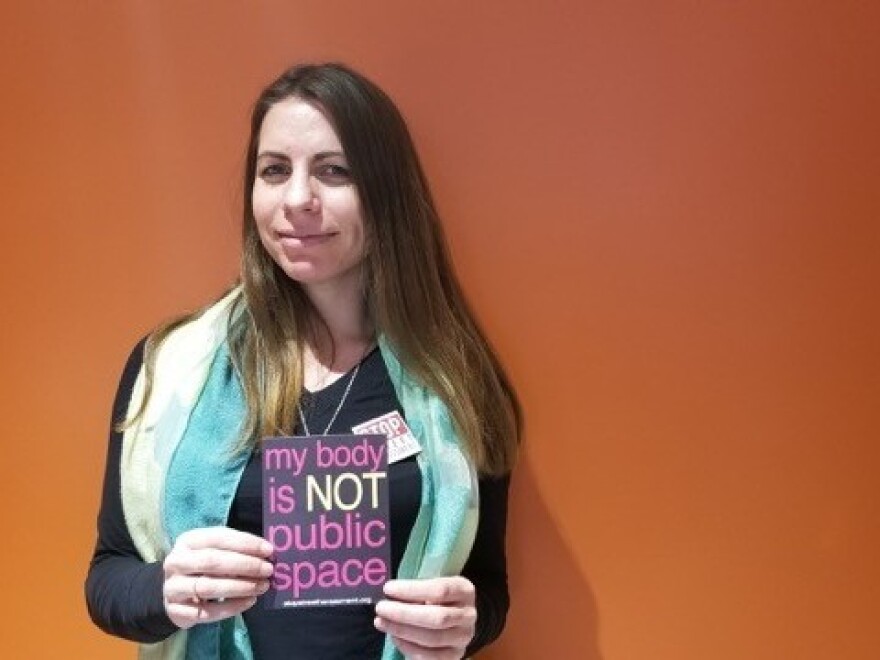

Inspired to act by the #MeToo movement taking place nationwide, Wroblewski decided to grab her camera and get to work. She began a series on Instagram called "I Was On The Metro When," publishing photographs of women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted on the transit system. Wroblewski has interviewed about 14 women who have faced anything from catcalling to public masturbation.

She is also crowdsourcing for more story contributions from women and men who have faced harassment on public transportation. Wroblewski ultimately wants to approach the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority about using her photos for anti-harassment campaigns within Metrorail stations and buses, replacing the agency's current ads.

"All the women that I've talked to really want to say something and want their voices heard," Wroblewski says. "I don't think there's been an outlet for them to do that."

Public spaces, like the Metro, are rife with incidents. Two years ago, Metro commissioned a study that showed roughly 20 percent of respondents faced some type of sexual harassment on regional public transportation. National statistics show a similar pattern.

It took a lot of lobbying from activists to persuade WMATA to even begin tracking harassment on its buses and trains. Holly Kearl with the advocacy group remembers approaching Metro leadership alongside other groups in 2012.

"The initial response we got was, 'One person's harassment is another person's flirting. It's not a problem on our system,'" Kearl says.

Kearl says that within a month of that meeting, the D.C. Metro was on board with what advocates were asking for. Now, Metro has partnered with Stop Street Harassment and other groups to put up anti-harassment ads throughout its system, and a Web page to report harassment. The agency is also running a revamped PSA — with Kearl as its voice.

Metro's 2016 study showed people aware of the campaigns were twice as likely to report harassment, and Metro is urging those who experience or witness harassment to report it, too.

"Then we start to build a database, start to track that," says Metro General Manager Paul Wiedefeld. "In case it does evolve, or we see a pattern start to evolve, we can get on top of it."

Critics of Metro's approach aren't sure reporting will amount to any action, especially in cases where the harassment may not be against the law — like verbal comments.

And while there's more work to be done, Holly Kearl says she believes Metro is doing what it can to tackle the issue.

"Sexual harassment is a rampant problem in all arenas in our life," Kearl says. "It would be unrealistic to expect one transit agency to solve it. We have to address the culture and change it."

And while that kind of change may not happen overnight, Kearl says this moment is the most promising she has seen in a long time.

Copyright 2021 WAMU 88.5. To see more, visit . 9(MDEwMTk5OTQ0MDEzNDkxMDYyMDQ2MjdiMw004))