The evicted tenant didn’t know where her three-person family would stay the night, how she’d move her belongings and pets, or even whether the dozen chicks huddled in a plastic tub would survive the chilly drizzle. She knew, though, that she wasn’t alone.

It was the day before Thanksgiving and two constables were inside of her former apartment on Wilkinsburg’s South Avenue. She had one car and needed to transport her fiance, the fiance’s teen son, their stuff, multiple dogs, cats, rabbits and parakeets — plus 30 chickens, including the hatchlings.

“It’s a shitty time for a hatch,” grumbled the tenant, as she looked down at the chicks. “I hope they don’t ... die.”

The tenant asked not to be named in the story, saying she was concerned about potential implications for her fiance’s son.

She had “no idea” what to do, but at least she had six volunteers from the United Neighborhood Defense Movement backing her. The anti-capitalist UNDM wants to thwart evictions, mostly in Pittsburgh’s eastern suburbs. Since mid-2020, the group’s Pittsburgh chapter has been part of a resurgent tenant activism energized by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The volunteers toted the tenant’s stuff. Later they raised money to cover relocation costs.

UNDM is not, however, a relief organization. Their aim is a world “in which tenants have the ability to say what they want and have it done because their enemies — the landlords, the city, the government — fear them,” said Andre Silverman, a UNDM member, in a later interview. The group is training for “eviction defense” actions that, members say, may include physical prevention of tenant ejections.

UNDM is perhaps the most ideologically strident of several tenants’ rights organizations that have either sprung to life, or become more active, in the year since the pandemic upended the rental housing market. Taking different approaches to tenant organizing are the Pittsburgh Union of Regional Renters [PURR] and the Landlord Watchlist Project.

Asked about tenant activism, Craig Kostelac, who runs North Huntingdon-based Crown Real Estate & Management Systems Inc. and the Landlord Service Bureau, blamed “unprecedented times, financially" and unclear pandemic-driven eviction rules for “creating angry tenants and angry landlords.“

"It’s not time for finger-pointing,” he said, adding that clarified eviction rules and more effective rent relief would be solutions “not based on politics, but based on what people truly need.”

Since the 1970s, tenant activism has ebbed and flowed in the Pittsburgh area. Pandemic-driven desperation, plus demographic change, could make 2021 a pivotal year for the movement.

“Black and Brown families have been dealing with this [housing] crisis for decades and centuries,” said Jala Rucker, director and organizer of PURR. The plight of low-income tenants is finally getting noticed, she said, “now that this pandemic has hit over the whole nation, now that it's affecting the lives of everyone other than [just] Black and Brown families”

PURR: ‘I feel like they care.’

Evictions are restricted through March, and while landlords continue to file cases, their numbers are below pre-pandemic levels. But the pandemic made ejection from housing more dire than usual, said activist Ronell Guy, who led the Northside Coalition for Fair Housing in the late 1990s and helped to launch PURR.

“COVID made people desperate to have space,” said Guy. “It’s not OK to lay up on somebody’s couch with your three kids anymore.”

Ebony Long, 35, once stayed in a women’s shelter with two preteen daughters. Now she has a 2-year-old son. “I don't want to go back to a shelter,” she said.

In mid-October, though, she got a handwritten note from her landlord giving her “30 days to Leave.” It came with another note giving her 15 days to vacate, citing “1 — unauthorized people in my house 2 — acting violently with them 3 — fearing for my security and safety 4 — causing much damage to house.”

Long said the “unauthorized people” were visiting relatives, that she was not the violent one during a “domestic thing” that occurred, and that she sacrificed her security deposit to address a broken window and other damage. She added that she paid some or all of her $900-a-month rent until October, when she lost her customer service job.

In a separate interview, landlord Ragab Refaei countered that Long’s high water bills, failure to pay rent and wear-and-tear on the apartment make it impossible for him to make up for the $25,000 he spent upgrading the house.

Long said she’d like to leave, but has no place to go. “At this time, it's kind of hard to even find a place.”

In November, Refaei formally filed to evict Long. Shortly thereafter, Long got information in the mail — possibly from a newly formed coalition’s Eviction Rapid Response initiative — that included PURR’s phone number.

PURR has connected her to aid programs and helped her to appeal the eviction, allowing her to pay rent via the court, Long said. "It's like someone actually cares. I feel like they care,” she said. She calls, “and they're there, they answer like that.”

Backed by a few low-five-figure grants and donations, PURR:

advocates for tenant protections, especially using its Twitter account

musters volunteers to go to district courts and give information to people facing eviction hearings

connects low-income renters with resources to help with a variety of problems.

“Someone’s texting me right now about how they need heaters because it’s cold. So we're going to figure that out,” said Jacob Klinger, a PURR organizer, during an interview conducted via Zoom.

“I have like two families that are chiming in to me,” added Rucker. “And they're probably going through a crisis right now.”

Rucker is a veteran tenant organizer. Klinger is a former reporter who quit over his former news outlet’s characterization of a neo-Nazi rally. They ultimately want to help renters to “fight back collectively,” Klinger said.

“And the idea is to have one big tenants union,” he said, so no one has to face a landlord alone. “If we could flip the dynamic from, you know, every landlord having one up over every tenant to the other way around, that would be good.”

Changing dynamics: ‘Not just the poor people’ anymore

Tenant advocacy is nothing new, especially in high-rent areas like New York and California.

“Tenants’ rights movements have been a long part of U.S. history,” said Alieza Durana, a journalist working for Eviction Lab, a research team based at Princeton University and led by Matthew Desmond, author of the 2016 book “Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City.” Durana cited tenant upheaval in the Great Depression, in the 1970s and during the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought “a lot of inspiration and leadership coming out of tenants unions.”

In Kansas City, Missouri, for instance, the group KC Tenants started the COVID-19 era pleading for an eviction moratorium and urging enforcement of their city’s year-old Tenants Bill of Rights. Frustrated in those efforts, it shifted to preventing evictions by whatever means necessary — including blocking courthouse doors, holding sit-ins and disrupting eviction hearings held online.

“We delayed 911 evictions in the Kansas City area in [January],” said Tara Raghuveer, founding director of KC Tenants. “That was 90% of the evictions that were attempted to be heard by the courts.”

Raghuveer suggested that the long-term impact may include the political awakening of a potentially potent demographic: the tenant mother.

“She is now so clear about what the institutions and what government are here to do, who they’re here to protect, who they work for. She knows it’s not her. And she’s pissed,” said Raghuveer. “The powers that be, who are letting us down, should be scared.”

Locally, public housing communities and some privately owned complexes have long had tenant councils. The Metropolitan Tenants Organization of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County advocated for public housing residents in the 1970s and 1980s. In the late 1990s, as the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh eliminated some communities and reduced unit counts in others, Guy created her North Side coalition, which remained active into 2019.

PURR emerged publicly by hosting a housing summit in November 2019. Last year, PURR helped with the emergence of at least two new tenant groups representing people who rent from JJ Land Company and Regent Square Rentals, also known as CP Development.

Guy sees broadening interest in tenant activism. “Now it’s not just the poor people,” she said. “There’s a whole lot of people who can’t find a place where they can afford to live.”

Landlord Watchlist Project: Posting ‘predatory acts’

Technology provides new options for engaging tenants. Click a link on the Landlord Watchlist Project’s website, and you get a survey, asking whether your landlord:

“Evicted me

Threatened to evict me

Sent an eviction notice without evicting me

Raised rent during the pandemic in an attempt to displace me

Cut utility service, refused to make repairs, and/or changed locks

Charged fees, penalties, or interest due to untimely rent payments

Moved another tenant in while I was living in the unit

Threatened tenant with bodily harm

Made my home uninhabitable (pest infestation, cut off heat, etc.)”

Launched in December, the project got 69 responses by mid-February. Tenants alleged each of the above scenarios except threats of harm, led by eviction threats (43%), fees and penalties (38%) and utility cuts or lockouts (31%).

What to do with such data? The volunteers at the Philadelphia-based volunteer group, launched in December and co-organized by North Sider Kaelin Mae Miller, are directing tenants to organizations that can help them.

They also plan to publicly identify “predatory” landlords, potentially posting them on an online “wall of shame.”

“If you’re a good landlord and you haven’t done predatory acts against your tenants, you don’t have much to worry about,” Miller said.

Even if they don’t fear the “wall of shame,” landlords might wince at the watchlist’s longer-term vision.

“I think we are at a really radical changing point in American history,” Miller said, “where we can really start to envision these principles and these ideals of what would our society look like if we didn’t have to pay rent.”

Landlords: Organizing is one thing, freezing rent another

Talk of canceling rent is naive and potentially damaging, according to Kostelac, whose Landlord Service Bureau caters to owners of small numbers of rental properties. “Where’s the fairness?” he asked. Canceling or freezing rent couldn’t work without canceling or freezing things landlords must pay — mortgages, insurance, taxes, utilities and maintenance, he said.

Saying that landlords can just eat those costs is “class warfare,” he said. “Class warfare isn’t healthy for this country.”

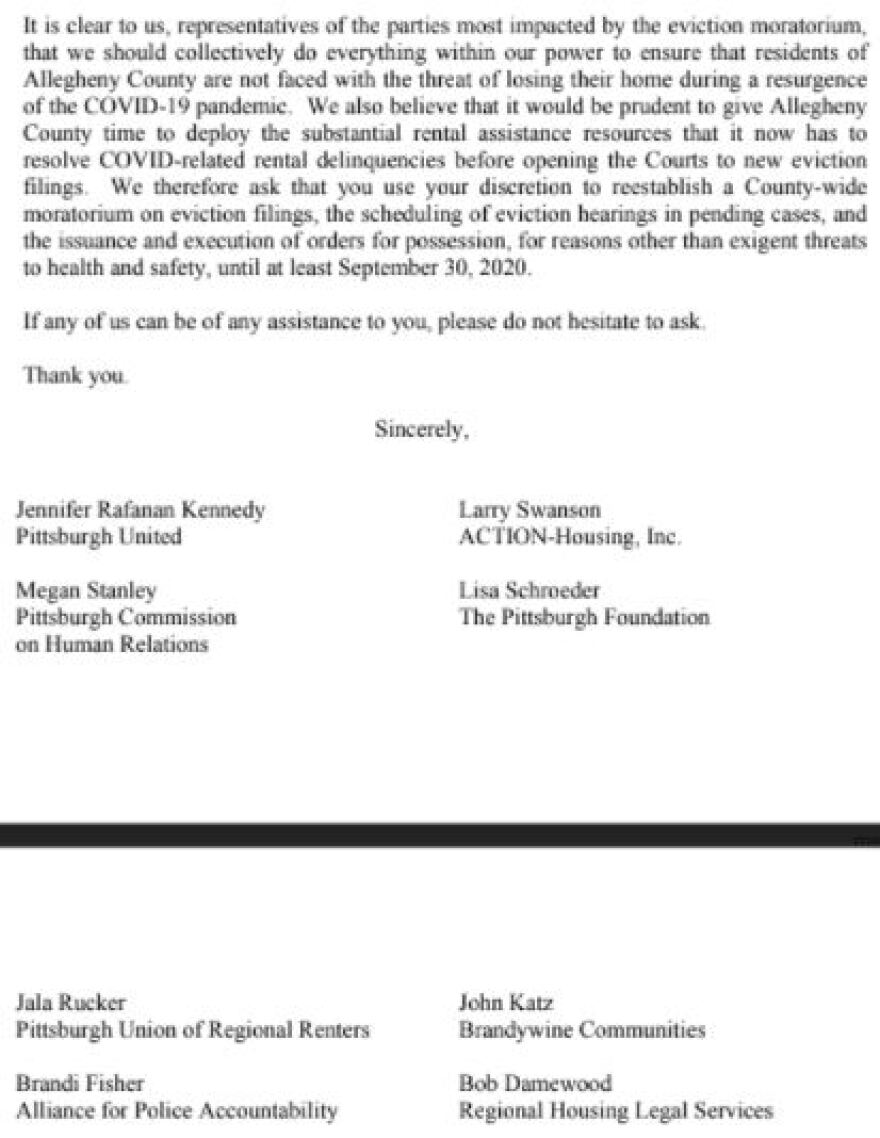

A few landlords have sided, in limited ways, with tenant activists. In July, two large, regional landlords — ACTION-Housing and Brandywine Agency — joined advocates including PURR in signing a letter to two Allegheny County judges, urging a full stop to evictions.

“Everyone deserves a home and the right to advocate for their family’s needs,” Brandywine President John Katz wrote to PublicSource in an email response to questions. “Organizing is how people build power, and I will always support that.”

Kyle Webster, nonprofit ACTION-Housing’s general counsel, said he’d “like to think that we are allies” with PURR, but they don’t always agree. “A very good example of that was last year, when there were a lot of calls by them and others around them to enact a rent freeze,” he said. A freeze, he said, would undercut the financial sustainability of rental properties.

“I think stuff like [freezing rent] is a bit idealistic,” he said, “but I think that we do need idealistic organizations out there advocating [to lawmakers] in order to get what is actually needed to be approved and passed.”

UNDM: ‘We won’t be puny forever.’

UNDM doesn’t hide its ideology. Its chapters in Los Angeles; Austin, Texas; Charlotte, N.C.; San Marcos, Texas; and Pittsburgh recently celebrated the work of Friedrich Engels, co-author with Karl Marx of The Communist Manifesto. Silverman talks about how “a class is bound together by being exploited or by exploiting.”

Usually, though, they tend to emphasize a more tangible mantra: Stop evictions.

UNDM member Alex Baker said the group is organizing anti-eviction squads, each made up of trained volunteers with "specifically delineated roles," like mobilizing the neighbors, making speeches, leading chants, watching out for the police and, where necessary, disrupting the effort to eject the tenant. She said the aim isn't "to call up people to just stand outside and say, like, 'This is bad.' We want to actually physically prevent it."

One target has been CP Development, Wilkinsburg’s largest landlord, and the one that ousted the chicken hobbyist on South Avenue. Last year, UNDM called for a rent strike against CP, protested outside of its offices and alleged that the borough was siding with the landlord.

In December, a CP employee told police that around 10 protesters, some carrying signs, banged on his windows and door, refused to leave and then took his “no trespassing” sign. A UNDM member was charged with misdemeanor stalking, theft and trespassing. There has, as yet, been no preliminary hearing in the matter.

CP’s owners declined to comment on UNDM but issued a statement noting that they are “a family-owned business” that has invested in abandoned and foreclosed properties. “We take care of all of our tenants and believe that the tenant/landlord relationship should be collaborative,” according to the statement.

Back on South Avenue, UNDM members did not appear to hinder the constables. Instead, they helped the tenant to carry her belongings out to the damp courtyard.

The eviction complaint against the tenant alleged that she violated the lease by subletting, having pets and smoking. The tenant, though, said she had been unemployed since March, and fell behind on rent despite paying some of her unemployment compensation to CP.

More Pittsburgh households now rent than own their homes, and landlords control a growing share of the housing market countywide. COVID-19 is testing the health of this market, bringing eviction curbs and rent relief. PublicSource and WESA are exploring these changes and examining the governmental and civic responses to the emergence of Tenant Cities.

The tenant said she asked CP to let her stay until Dec. 5 when another landlord was willing to take in her family, but CP was "absolutely not budging.”

Baker later claimed that UNDM delayed the family’s ejection, giving them time to prepare and find alternative shelter. She added that the group raised more than $1,000 to help with the family’s relocation to a “little farmhouse.”

UNDM hasn’t yet mustered the 25-person fighting force they’d ideally like to have to thwart evictions. "We are weak and the enemy is strong, but there is a long-term trajectory,” said Silverman. “Laws of history show that we are going to be strong, and the enemy is going to be weak. ... So puniness for us is not the problem because we won't be puny forever."

Margaret J. Krauss contributed to this report.

Rich Lord is PublicSource’s economic development reporter. He can be reached at rich@publicsource.org or on Twitter@richelord.

This story was fact-checked by Matt Maielli.