Posing with a new gun, from the top of a tall building or on a seaside cliff are just some of the ways more than 127 people died taking selfies between 2014 and 2016.

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University and the Indraprastha Institute of Information Technology in Delhi, India found that number in a study of selfie-related deaths. The team is now using the data to help prevent future casualties-by-selfie.

IIITD associate professor Ponnurangam Kumaraguru said he and his group of computer scientists are developing an app that would warn smart phone users if the picture they’re about to take could be dangerous.

“You’ll be able to find out information about that location and see whether it is safe for a selfie or not,” Kumaraguru said. “If it’s very dangerous, the camera may not even be enabled when you want to take a picture.”

Between March 2014 and September 2016, Kumaraguru and the researchers used algorithms in Twitter and discovered 127 selfie-related deaths throughout various countries. Of those, 76 took place in India, nine in Pakistan, eight in the United States and six in Russia. Kumaraguru said he thinks India has the highest number of casualties because of its dense population and recent boom in smart phone access.

Of the 127 incidents, 24 involved groups, meaning “multiple deaths were reported in a single incident,” according to the report. The rest were individual events.

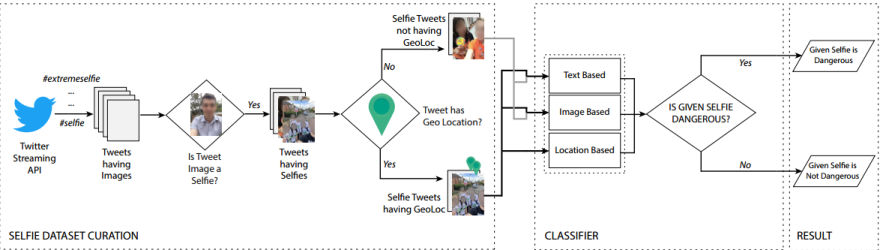

Researchers said they chose Twitter because of its Streaming API interfacing, meaning data and tweets could be extracted in real time. To compile the list of 127, they searched hashtags including #dangerousselfie, #extremeselfie, #drivingselfie and #letmetakeaselfie.

From those nearly 138,000 results, they found 91,059 had images and 62,000 of those were actual selfies. From there, they eliminated images without Geo Location enabled, leaving about 6,842.

To determine if the selfies were dangerous or not, researchers set criteria for the photos. They could classify them as dangerous if they were taken from a certain elevation or if they were in close proximity to a body of water, or both.

Kumaraguru said from there, they were able to rank the danger of the selfie circumstance.

“The most one was the height, which is the elevation of the building, the next one is the water body, then the train, then weapons, vehicles, electricity and animals,” Karamaguru said.

Of course, not everyone who falls victim to these dangerous selfies knew taking the photograph would put them in danger. Karamaguru said sometimes the deaths are purely accidental or circumstantial.

“So there’s two types of death that are happening: one is trying to take a dangerous selfie and then dying and the other is just taking a selfie and then dying,” Karamaguru said.

The United States and Russia were the only two countries that had weapons-related selfie deaths. In India, a high number of deaths occurred on train tracks and in or around bodies of water. Men were much more likely to die by taking a selfie than women.

“Adventure photographers,” as they’ve been called, popularized the dangerous selfie trend, taking pictures from high above cities and out of airplane cockpits. In 2015, a report revealed more people died from taking risky selfies than by shark attacks that year. Some countries have even created “no-selfie zones” to protect citizens.

Since the research was released, Karamaguru said he understands that many times the situations they studied could have been easily prevented, but at this point, he and his team plan to use the data they've acquired to focus on finding a solution.

“Building technologies to solve problems like this is always exciting,” Karamaguru said. “Particularly when there is life involved, I think solving these kinds of problems is becoming more and more necessary to do.”

The study, called “Me, Myself and My Killfie: Characterizing and Preventing Selfie Deaths,” received no special funding. Karamaguru said "the project was done out of passion and interest."

(Photo credit: Rodrigo Olivera/flickr)