It was 1944, and workers at the Penola grease plant, on the edge of Pittsburgh’s Strip District, might not have known who Gordon Parks was. But the young Black photographer was about to capture them on film for posterity.

Today, the late Parks is known as a pioneering photojournalist and filmmaker – the first Black director to make a film for a Hollywood studio. Most of the dramatic images he shot of Black and white men at work at Penola during and just after World War II have never been seen by the public. But starting Saturday, they’re the focus of a “Gordon Parks in Pittsburgh, 1944/1946,” a new exhibit at the Carnegie Museum of Art.

Parks, a native of Kansas, began his photography career shooting fashion in Chicago, and documenting Depression-era laborers for the U.S. Farm Security Administration, under famed photographer Roy Stryker. It was Stryker who hired him for a private-sector commission: essentially, a public-relations project for Standard Oil, to show how its subsidiary Penola was contributing to the Allied war effort. The plant made “Eisenhower grease,” a petroleum product that provided lubrication and waterproofing for military vehicles.

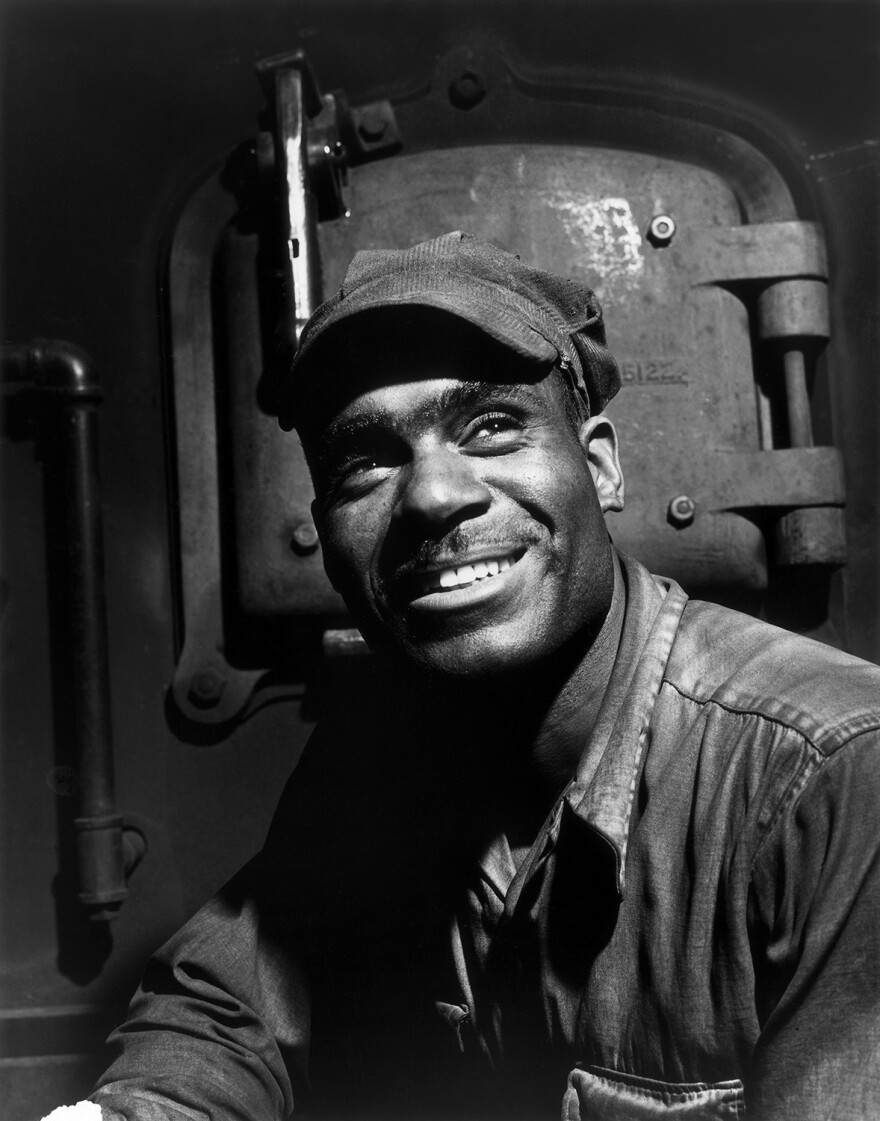

Parks shot at the plant in March 1944 and again in September 1946, said Dan Leers, the Carnegie’s curator of photography. He took hundreds of dramatic, black-and-white photos, many of them spotlighting the plant’s Black workers, often in ways that subtly suggest the racial segregation at the plant.

But only one of those images has come down as part of his photographic legacy: an iconic, low-angle shot of a Black workman lifting a barrel from a boiling lye solution against a backdrop of steam.

Leers tracked down more images, most from the Gordon Parks Foundation, and others from sources including the Library of Congress and the George Eastman Museum. The exhibit includes more than 50 taken on both the sprawling plant’s upper level, where the chemicals were mixed, and the ground floor, where they were heated and the metal drums were filled for shipping. The collection includes both posed group and individual portraits of the workers as well as images of them in action. Leers said that though this was a commercial job for Parks, the results reflected his humanistic approach.

“He says one of the best ways to understand somebody’s character is to photograph them in their surroundings at their job,” said Leers. “These are composed photographs … and yet there is something very beautiful and insightful about the pictures that he makes of these individuals either doing their work or stopping and posing with a piece of equipment that they’re using.”

“These portraits, I think, they help tell the story of the work, but they also help tell the story of the city, they help tell the story of industry in general,” Leers added.

Parks was born in 1912, the last of 15 children. He grew up in segregated Fort Scott Kansas, and as a young man worked jobs including railway porter.

“He knew what it meant to put in a day’s work, and he had a real appreciation for that and so I think these portraits that he made were his way of kind of paying tribute to these people and the work that they do,” said Leers.

After the war, Parks became the first Black staff photographer at LIFE magazine, as well as the first Black photographer for Vogue. He was that rare photographer who contributed to the canons of civil-rights activism, celebrity photography, and fashion. Leers compares his career to that of Pittsburgh's own Charles "Teenie" Harris, who documented Black life here for the Pittsburgh Courier for decades. The new exhibit includes an enlargement of Harris' photo of Parks visiting the Courier's printing presses in the 1940s, when, Leers said, Parks was already well-known to Black audiences.

In 1969, Parks distinguished himself further when Warner Bros.-Seven Arts hired him to write and direct the big-screen adaptation of his semi-autobiographical novel “The Learning Tree,” making him the first Black person to do that for a major studio. Even more famously, he directed “Shaft,” the hit 1971 action movie about a Black private eye that is widely credited with launching the so-called Blaxploitation genre.

Parks died in 2006.

The Penola plant (also known simply as the Pittsburgh Grease Plant) remained open until 1999, according to a state historical marker at the site, at 33rd and Smallman streets. Leers said the Carnegie hopes to hear from visitors who know people in Parks’ photos, or even who worked at the plant themselves.

“Gordon Parks in Pittsburgh, 1944/1946” runs through Aug. 7. More information is here.