A flurry of climate reports came out this fall — from the United Nations and the U.S. government — painting a dire picture of the challenges facing the globe.

Here’s a look at how Pennsylvania has been working to reduce emissions in 2018 and a preview of what may be in store for next year.

Climate reports

A special report from the UN in October said that by 2040, the world faces myriad crises — including food shortages, extreme weather, wildfires and a mass die-off of coral reefs — unless emissions are cut sharply.

The scientists wrote the report expressly for policymakers. They’re urging governments to try to keep the warming to less than 1.5 Celsius above pre-industrial levels. That’s half a degree lower than the goal set by the 2015 Paris Climate Accord. They conceded that there is “no documented historic precedent” for such a rapid transformation of the global economy. News came this month that global emissions in 2018 reached a record high, as representatives from countries across the world met in Poland to figure out how to achieve the pledges made three years ago in Paris.

The Fourth National Climate Assessment, a congressionally-mandated report, was released by the Trump administration in November and says the Northeastern U.S. is warming faster than any other part of the lower 48 states. Another UN report published last month shows countries are far off the mark in meeting the necessary emissions reductions. Although Pennsylvania has a small share of the global population, it is an energy powerhouse that is both historically — and currently — a major source of harmful emissions. Among states, Pennsylvania is the third largest carbon polluter.

A draft update of Pennsylvania’s Climate Action Plan was released in November by the state Department of Environmental Protection. It calls for an 80 percent reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, from 2005 levels. It outlines 19 strategies for addressing climate change, including promoting clean energy, energy efficiency, monitoring ecosystems vulnerabilities, and providing resources to help farmers and the outdoor tourism industry adapt.

Climate-related risks to Pennsylvanians include frequent extreme weather events, injury and death from those events, and threats to human health through air pollution, diminished water quality, and heat stress, according to the report. The warming will also affect farmers as it presents changing pest, weed, and disease management challenges.

2018 was Pennsylvania’s wettest year on record, according to Pennsylvania State Climatologist Kyle Imhoff. The statewide total precipitation average (ending Nov. 30) was 59.43 inches — that’s more than 20 inches above the average for the period from 1901 through 2000. The year’s wet weather cannot be directly attributed to climate change. However, climate models predict the region will experience more precipitation as temperatures continue to rise. The state’s Climate Action Plan says annual precipitation in Pennsylvania has increased by about 10 percent since the early 20th century and is expected to increase by another 8 percent by 2050.

The Wolf administration also recently put out a report calling for a major increase in the use of solar energy. Under the state’s current Alternative Energy Portfolio Standard, Pennsylvania is on track to produce half-a-percent of its electricity from solar sources by 2021. The new plan, called Finding Pennsylvania’s Solar Future, sets a much more ambitious goal — 10 percent by 2030.

Public opinion

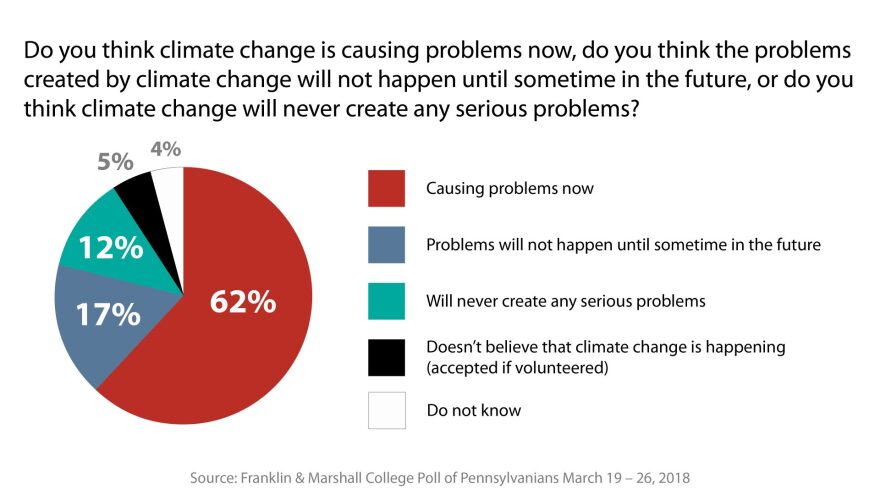

A majority of Pennsylvania voters agree with the scientific consensus that climate change is causing problems right now, and more than two-thirds say the state should be doing more to address it, according to a Franklin & Marshall College/StateImpact Pennsylvania poll published in March.

Party affiliation and political ideology continue to play a big role in people’s views, with Democrats and independents being much more likely to believe climate change is happening. However, almost two-thirds of Republicans in the survey said climate change is causing problems now or will at some point.

A national Gallup survey published the same month showed 45 percent of Americans believe the warming will pose a serious threat in their lifetime. That’s the highest percentage recorded since Gallup first asked the question in 1997.

Policies

Despite the partisan divide, Pennsylvania lawmakers managed to pass some climate-friendly legislation in 2018.

In June, Gov. Wolf signed a bipartisan bill aimed at helping commercial property owners finance the costs of installing clean energy upgrades. Known as Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy, the measure creates a voluntary program, allowing municipal governments to set up energy improvement districts. Private lenders then give money to agricultural, commercial, or industrial property owners who want to finance energy-efficiency and clean technology upgrades, such as solar panels, water pumps, or insulation. The loan is repaid through a tax payment that remains attached to the upgraded building, even if the owner later relocates and sells the property. Nearly three dozen other states and Washington D.C. have adopted similar programs.

The same month, Wolf signed Act 58, which gives the state’s Public Utility Commission a new range of options in crafting electricity rate designs. Known as alternative ratemaking, the new law gives utilities ways to recoup their costs a time when electricity consumption has been flatlining.

That matters for climate change, because before the new law, electric utilities had an incentive to push for increased usage— that’s what drove their investments into infrastructure and a guaranteed return from regulators on those investments. Utilities will now have more options for generating revenue, although consumer advocates worry the language in the law is too vague and ratepayers could wind up paying more than their fair share.

In December, the Wolf administration announced it was joining a coalition of eight Northeast states, and Washington D.C., to create a program to reduce carbon emissions from vehicles. The states are Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont and Virginia. The coalition pledged to draft a policy within one year, creating a “regional low-carbon transportation policy proposal that would cap and reduce carbon emissions from the combustion of transportation fuels through a cap-and-invest program or other pricing mechanism.” After that, each state will determine whether to adopt it.

Cap-and-trade petition

In a petition filed last month, a coalition of environmental groups, legal scholars and solar energy firms are trying to compel Pennsylvania to establish an economy-wide cap-and-trade program in Pennsylvania, using California’s system as a model.

The petition triggers a legal process, requiring a response from the state. Gov. Wolf recently said he has not “come to a conclusion” on it, but that he sees climate change as “one of the big issues we have to deal with.” If the petition were embraced by the Wolf administration, it could be a way to enact significant climate policy on the state’s power sector through a regulatory approach, largely circumventing the Republican-led legislature. The petition could also provide a pathway for Pennsylvania to join the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative — a carbon trading program among nine Northeast states. Joining that effort is something Wolf pledged to do during his 2014 campaign for governor.

The petitioners are hinging their argument on Article 1 Section 27 of Pennsylvania’s constitution — commonly known as the Environmental Rights Amendment. It was added in 1971 and guarantees citizens the right to clean air and pure water. It also requires the state to act as a trustee of the public natural resources for all the people, including “generations yet to come.” After being largely ignored for decades, the amendment has seen a resurgence following two recent state Supreme Court decisions. The petitioners argue that provides a constitutional requirement for the state to act on climate change.

Looking ahead to 2019

There will be a big push in the legislature next year to provide help to Pennsylvania’s nuclear industry, which is struggling economically.

Two of the state’s five plants are set to close prematurely. Other states have recently helped prop up their nuclear fleets, and it’s often been coupled with increased clean energy targets. Pennsylvania has a 2004 law called the Alternative Energy Portfolio Standard that requires utilities to get 8 percent of their power from so-called “Tier 1” clean sources by 2021. Nuclear advocates want the state to recognize their power plants as a clean source of carbon-free emissions. Environmental advocates would likely want to wrap up anything for nuclear plants with increases to the AEPS — they want bigger carve outs for wind and solar too.

Opposition is coming from consumer groups, such as the AARP, which says aid for the nuclear industry will increase costs to ratepayers. The natural gas industry, which has a powerful lobby in Pennsylvania and has been increasing its share of electric power generation, also opposes the effort, arguing the aid would be unfair, and threaten competitive wholesale electricity markets.

This story is produced in partnership with StateImpact Pennsylvania, a collaboration among WESA, The Allegheny Front, WITF and WHYY.