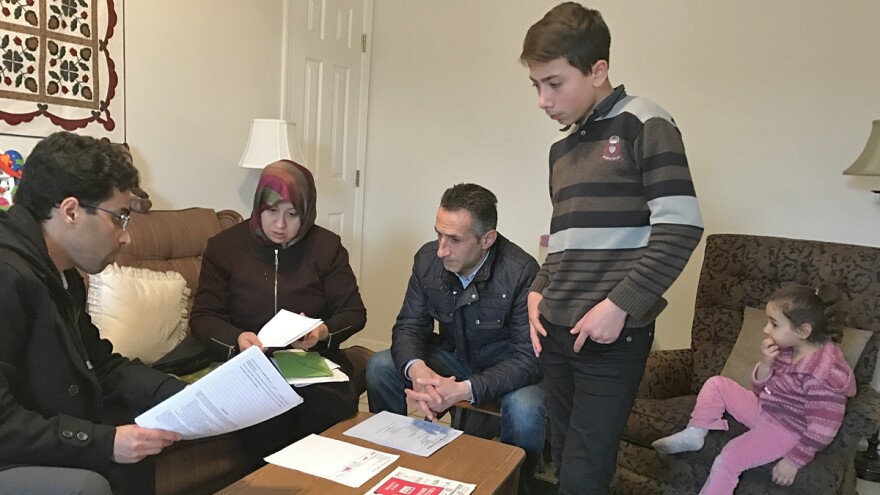

Imad Ghajar and his wife Marwa Hilani were born in Aleppo, Syria, met there, and didn't have plans to leave.

Then the war happened.

"Even in the schools, there wasn't security," Marwa, 37, said recently, through a translator, at her family's new home in Lancaster. "In the middle of the day, there would be a bomb, and someone would die. The area was not safe ever."

The dust from the explosions also made their daughter's asthma worse, and it was increasingly difficult and dangerous to get her treatment.

"We['d sit] in the middle of the house," said Imad, 42. "We wouldn't let the kids leave. Even to another room or the balcony. It was like that for a year and then we went to Turkey."

They fled in November 2015, the day after explosives brought down the building across the street, and say they started the refugee resettlement process fairly quickly.

More than two years later, after a brief stay in Turkey, Imad and his family arrived in Lancaster, some of the last refugees expected for the foreseeable future.

"We don't have any arrivals scheduled at all," said Valentina Ross, resettlement coordinator at Church World Service's Lancaster office. "That's highly unusual for our program."

Some resettlement agencies (including HIAS offices in Philadelphia, for example) are expecting refugees to arrive in the coming weeks.

But fewer refugees have received confirmation to travel to the U.S. recently in anticipation of President Trump's executive order this week, and reduced admissions ceiling, according to the Department of State, to 50,000 refugees. That's half of what was planned for the fiscal year ending in October.

Resettlement agencies also see a drop-off in caseload if they supported Cuban migrants who entered the U.S. under the "wet-foot/dry-foot policy" ended by former President Barack Obama just before leaving office.

Ross says there are two main issues.

"Putting such a long halt will decimate the capacity of resettlement agencies to continue to provide the same level of services," she said. "And having lowered ceiling so much in midst of worst world refugee crisis that has ever existed. This is not compatible with the history of acceptance of the United States."

The order says suspending resettlement is necessary for an in-depth review of the screening process.

Right now, the screening takes up to three years.

It involves at least half a dozen interviews, three separate fingerprint screenings, and scrutiny of social media activity and travel patterns, among other things, by various intelligence and national security agencies.

For Imad and Marwa, it also entailed long bus rides to take care of the screening: five hours to Ankara; 12 to Istanbul.

In the meantime, the family struggled. Imad and Marwa say they experienced discrimination.

It was tough to secure an apartment in the city of Kayseri. Imad, a tailor by trade, says he wasn't paid fairly for his work. Their eldest son couldn't attend school, Marwa said.

[Nearly 3 million Syrian refugees are registered in Turkey, where they've been fleeing since the civil war started in 2011. But Turkish officials say they expected to provide only temporary support and haven't engaged longer-term strategies for Syrian refugees, so tension has continued to grow over the resulting economic and infrastructural strain.]

And while Kayseri was safer than Aleppo had become, it wasn't exactly secure, the couple says.

Not long after Imad and Marwa finished the screening process and booked their trip to the U.S., the first travel ban was issued.

Marwa says the ban inspired feelings that lingered, even after it was lifted and they could go to the U.S.

"I was very afraid of traveling here after Trump's decision, and I was surprised at my reception here — it was so good," she says.

Imad put it this way:

"Even when we arrived here in a small airport, there was such a nice welcoming group for us. Then I was so, as my wife said, afraid. But I was walking in the street and I saw a sign which said: It doesn't matter where you were born — it is enough that you are our neighbor. Now, I feel like I am in my country."

Find this report and others at the site of our partner, Keystone Crossroads.