Pennsylvanians sentenced as adults to life in prison without parole can only be released if the governor commutes their sentences. For most of the past 25 years, that's happened no more than once annually.

But Governor Tom Wolf has granted the relief six times within the last eight months – and more may come after the state’s Board of Pardons meets this week. On Friday, the board will hear 21 pleas for commutation.

According to pardons staff, the board hasn't considered that many petitions at a single hearing in at least a quarter century. It's more than triple the number the board heard at its previous meeting in May.

The board holds commutation hearings four times a year. Advocates get 15 minutes to say why their clients deserve commutation.

By that time, inmates have usually waited for about three years after submitting their applications for commutation. The hearing is the last step before the board advises the governor on who to release early.

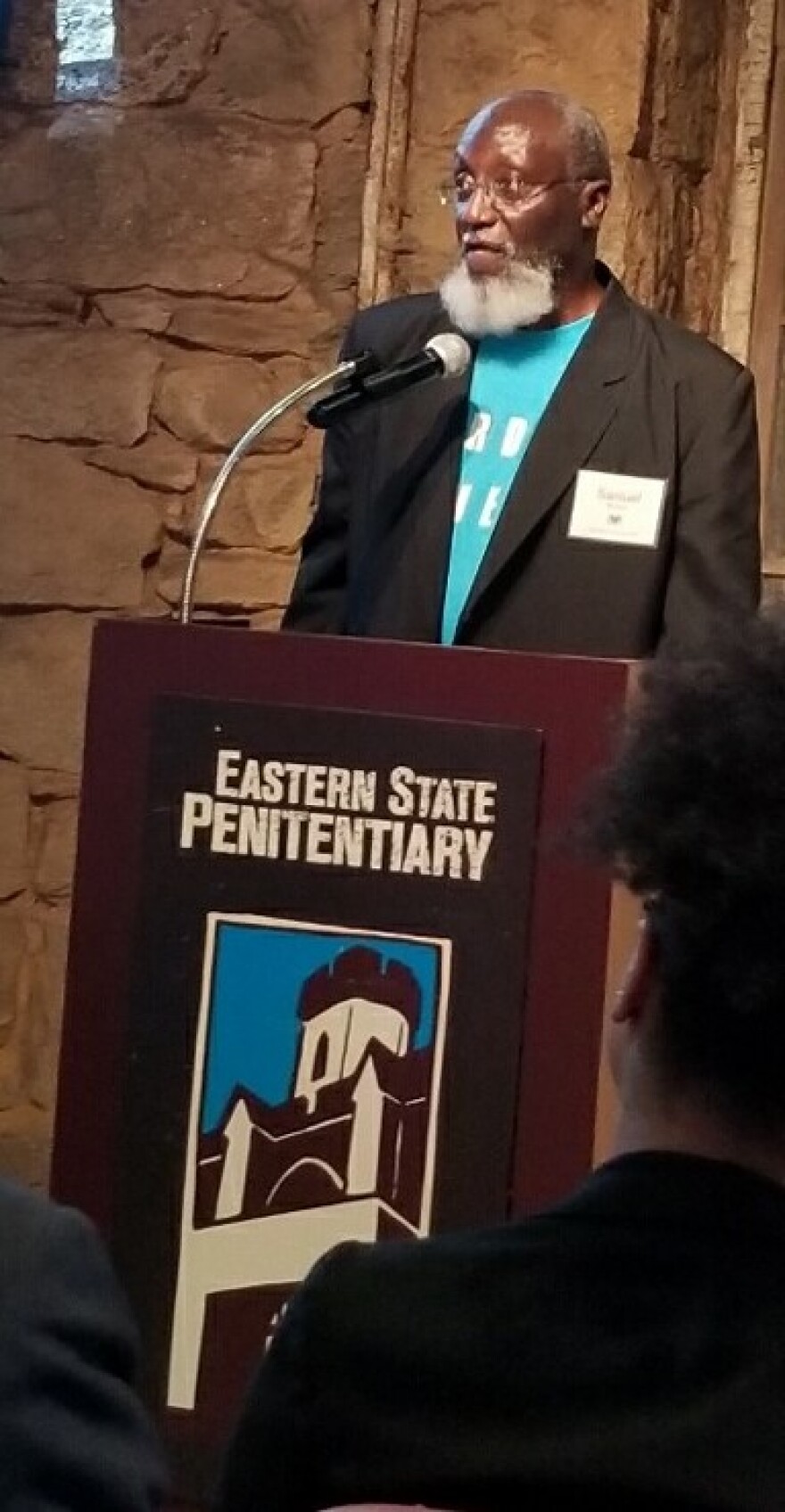

Inmates themselves do not appear at the hearing. But Sam Barlow, whose sentence was commuted in April, said they speak with the board’s five members the day before, at a state prison across the river from Harrisburg.

“You’re shackled, and they escort you into this room. And they have you sitting there with a table,” Barlow remembered. “And the lieutenant governor, he’s no nonsense. So, he says, ‘Listen, tell me who you are, why you’re here, and what you want from us.’”

Barlow told the board he’d been incarcerated since 1968 after taking part in a robbery where a man was killed. He didn’t shoot the man, but drove his two accomplices to the scene of the crime.

Barlow then took questions from four of the board members: a victim representative, a corrections expert, a psychiatrist, and the state’s attorney general. They asked about his conduct behind bars and what he would do if released. Then, Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman weighed in. Fetterman, who chairs the pardons board, observed that Barlow had been in jail since before Fetterman was born.

“I said, ‘Well, I don’t know how old you are, but I’ve been in jail for 50 years and 5 months,’" Barlow recalled. "He said, ‘Unbelievable.’"

Cases like Barlow’s have prompted Fetterman, 50, to push for more commutations.

“We as a society, I think, need to ask ourselves, how much is enough?" Fetterman said. "Do you believe in perpetual punishment? Or, do you believe in a second chance?”

'I'm actually home'

Until this summer, Robert Wideman was one of more than 5,100 Pennsylvania prisoners serving life sentences without the possibility of parole. But his sentence was commuted this spring, after he spent 43 years behind bars.

Now free, Wideman spends most of his days with Vivian Carter, his girlfriend of seven years. Carter loves to cook for Wideman, and said she makes him bacon and eggs every day.

Wideman said he's still astounded by how his circumstances have changed.

“I’ve got to keep looking around and saying that I’m actually here,” he chuckles. “I’m actually home.”

In 1975, Wideman participated in a botched robbery in which a man was fatally shot.

“I hold that as the greatest mistake of my life. I hold that as the sin that might curse me forever,” Wideman said.

Such remorse is crucial to earning commutation. But family members of Wideman’s victim strongly opposed his release.

The state’s Office of the Victim Advocate and county district attorney’s offices are required by law to notify victims’ families when a perpetrator is being considered for commutation.

While some families feel that decades behind bars is long enough, Pennsylvania’s victim advocate, Jennifer Storm, said more often they argue they were promised a life sentence.

“And it’s often coupled with comments like, ‘My loved one doesn’t get a second chance. My brother or my sister or my husband, my wife, my child is not here today,’” Storm said.

Shifting priorities

Those attitudes have prevailed for the past few decades, especially since 1994, when a man named Reginald McFadden killed two people and raped another after receiving commutation.

“That received a lot of publicity," said federal Judge Mike Fisher, who then was a Pennsylvania state senator. "And the question was, who was Reginald McFadden? Where did he come from?”

At the time, lifers could get released with a simple majority vote from the pardons board. But Fisher introduced legislation to amend the state constitution to require the board's unanimous support.

“I thought that that was maybe something that would give the people of Pennsylvania assurance that only the right people would qualify for it,” Fisher recalled.

Voters approved the amendment in 1997, and the odds have been stacked against inmates ever since.

While Fetterman said it is important to protect public safety and victims' rights, he added that the state must "temper" those concerns "with mercy and with an overall belief that people deserve a second chance if they’ve definitely made a good-faith effort to rebuild their lives and take accountability for what they’ve done."

The lieutenant governor said he'd like to return to pre-1980s levels, when an average of 20 to 30 sentences a year were commuted.

“That’s my goal,” Fetterman said, “that there is not one single deserving soul rotting away in Pennsylvania prison that we can do something about.”