In most states, the legislature is in charge of designing Congressional and state voting districts.

Pennsylvania isn’t unique in that respect.

But some say the commonwealth is home to some of the nation’s starkest examples of gerrymandering — where the shape of a voting district is manipulated to produce the outcome desired by the party in charge.

The term is over 200 years old. It was coined by a Boston newspaper’s coverage of maps produced in Massachusetts in 1812 during the term of Gov. Elbridge Gerry, which featured a salamander-shaped district loosely coiled around Boston.

To this day, politicians on both sides of the aisle seem to be doing their best to make it an immortal turn of phrase.

Pennsylvania’s most recent congressional map, drawn in 2011, is known as a particularly egregious example.

“Pennsylvania is one of the worst states this decade in terms of its congressional map,” said Michael Li, senior redistricting counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law.

So, how do we know it’s bad?

Li helped lead the study behind the center’s “Extreme Maps” report that came out earlier this year.

He says the strange shapes of Congressional districts can result from mapmakers simply following municipal or county boundaries, but other times there are clearly political forces at play.

He hopes his work can be used as an objective gauge to give courts the “comfort” to strike down redistricting efforts that “go too far.”

“There are legitimate political considerations that go into making a map….what isn’t fair is when you put your thumb on the scale and take a disproportionate share of seats and lock it in, and [perpetuate] a lack of accountability,” he said. “Courts have had a hard time figuring out when that is. These tests give some statistical evidence of when that occurs.”

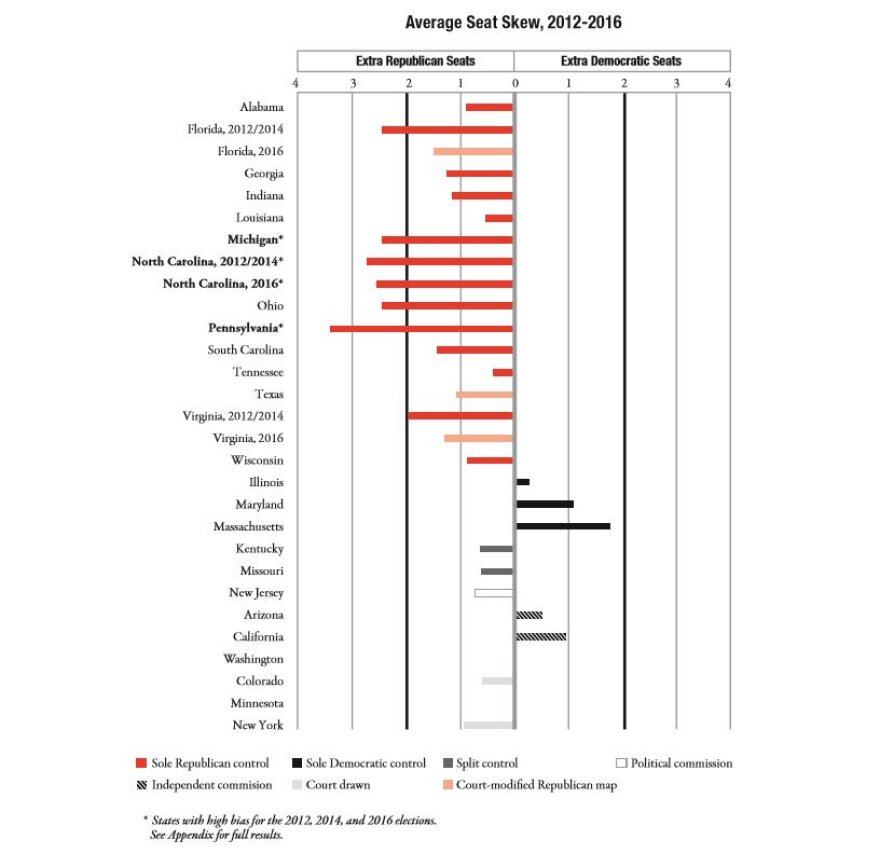

Researchers ran Congressional election data through three different indices to measure disparities between election outcomes and expectations — looking at how many seats each party won versus what statewide vote totals might suggest. They also compared mean and median vote totals in each district and analyzed whether the differences were statistically more attributable to chance or manipulation.

“When you look at these three tests, for two of them, Pennsylvania is the worst in the country and the other it’s the third worst state. So that’s a really strong indication that someone put the thumb on the scale in Pennsylvania and produced an unnatural result,” he said.

North Carolina and Michigan are up there, too. The study also found partisan bias in Florida, Texas, Ohio, Virginia and Massachusetts — but less severely.

Why these states, in particular?

A few things jump out from the study.

One is geography. Li says the worst gerrymanders are in battleground states like Pennsylvania. Basically, if voters of different political stripes are mixed together in enough areas, mapmakers have more options.

The other two work in tandem: a state’s process for redistricting and single-party control.

“When the legislature’s split or you have governor of opposite party who can veto a bill, you don’t actually have extreme maps,” Li said. “Likewise, when court draws a map or a commission draws the map. This is really a problem that exists when one party has all the marbles and keeps those marbles and doesn’t involve the other party or other people or independence in the process.”

States redistrict every ten years following the U.S. Census. In both 2011 and 2001, Republicans in Pennsylvania dominated the entire process.

They held both chambers of the General Assembly, which directly establishes Congressional maps and appoints a bipartisan commission to handle legislative districts.

They held the governor’s office, which maintains veto power over the legislature’s product.

And the state Supreme Court — which steps in if there’s a veto, legal challenge or disagreement over commission appointment — was held by a majority of justices elected as Republicans.

Currently, despite a 25 percent edge for Democrats in statewide voter registration totals, Pennsylvania’s Congressional delegation includes 13 Republicans and five Democrats.

Li says the influence of politics on Pennsylvania’s map is so clear that “you almost don’t need the tests.”

Pennsylvania also appears prominently in books written on the subject, including David Daley’s 2016 volume in which he interviews GOP operatives about their concerted gerrymandering efforts. They tell him they focused especially on Pennsylvania, Michigan and North Carolina — in addition to Florida, Ohio and Wisconsin, which produced a U.S. Supreme Court case that was argued in October.

Maryland is thought of as a notable example of gerrymandering orchestrated by Democrats.

The effect redistricting efforts have on politics can be overstated, though.

For instance, Daley acknowledges the role of the rise the Tea Party during the same timeframe that Republicans garnered more power in Pennsylvania’s congressional delegation.

And some analysts say Pennsylvania’s state legislature would’ve grown in Republican might without gerrymandering — attributing gains more to the party’s talent for focusing on local races, grooming up-and-comers, and consistently compelling voters to the polls even during off-year elections.

And some political disparities in Pennsylvania exist without the help of any mapmaking trickery. Since 1979, the majority of counties have been run by Republicans (currently, 53 of 67 counties), according to records provided by the County Commissioners Association of Pennsylvania.

Learning to ‘play ball’

But at a deeper, existential level, onlookers of Pennsylvania politics say the state is ripe for redistricting abuse.

“It goes hand in hand with lack of reform in this state on some kind of redistricting that doesn’t have partisanship intimately tied to it,” said Terry Madonna, who runs the Center for Politics and Public Affairs at Franklin and Marshall College in Lancaster.

He thinks it’s partly a holdover from the machine politics of Pennsylvania’s past.

“Forty state legislators over the past 30-some years [have been] indicted and convicted of a variety of public corruption charges, and not one of them censured or reprimanded by the ethics chamber in the House or the Senate,” Madonna said.

To Madonna’s point, Pennsylvania has performed poorly in multiple good government rankings and comparative studies

The state flunked a 2015 grading by the Center for Public Integrity, received a ‘C’ for its lobbying laws by the Sunlight Foundation, and was near the bottom of analyses of campaign contribution limits by both Sunlight and the National Center on Money in State Politics. To boot, it has open meetings rules that are decried by transparency advocates.

Pennsylvania did fare well in Open States’ grading of states’ data access and retention policies, although legislators are exempt from the public records laws here as in most states.

Pennsylvania also lacks public referendum, which lets voters legislate directly if there’s enough support to get a measure on the ballot.

That’s one of the avenues that has spurred redistricting change elsewhere. In California, direct voter referendum drove a redistricting overhaul in 2008, and an independent commission now creates the maps.

Based on that example, Carol Kuniholm, who heads Fair Districts Pennsylvania, says she reached out to her counterparts in the Golden State.

“Those same groups, when we began our work here in Pennsylvania, [they] said, ‘it would be a really valuable and important and impactful change for Pennsylvania, but we don’t see a path forward for you,’ because we don’t have that option of initiative and referendum,” Kuniholm said.

Fair Districts has also lobbied for a legislative fix. Their favored bills are now co-sponsored by nearly half of both the House and Senate. But the bills have been stuck in committee for months.

That happens with all kinds of bills, in all legislative bodies.

But arguably, Pennsylvania state legislators have a strong incentive against overhauling the system that brought them power. Lawmakers receive an $86,000 dollar starting salary, second only to California’s, and they enjoy a top tier daily allowance while they’re in session, according to data from the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Madonna says all of these factors contribute to a status-quo that undermine efforts to create a fairer electoral system in the state. He says it grinds down even the lawmakers seeking change.

“After they get into office for a while and they’ve tried, but don’t get successful reform, they just become part of the establishment and understand if they want to get something done, they have to play ball with the leadership,” Madonna said. “And so there’s just not pressure among the membership for much to occur.”

Voter referendum and other ethical reforms seem to be non-starters on the Pennsylvania political horizon. So Madonna says court intervention is the state’s best chance for fairer maps.

The Pa. Supreme Court, controlled by elected Democrats since 2015, agreed last week to fast-track one of the cases challenging the constitutionality of the congressional map. Another case is being heard at the federal level.

Advocates like Fair Districts PA hope one of these will lead to a new map before the 2018 midterm elections.

This story is the first in Keystone Crossroads' redistricting series “Over the Line”, a collaboration with PennLive, WITF and other public media stations across the state.