On the wind-whipped hills north of Haiti's capital, Port-au-Prince, Berthenid Dasny holds the keys to the gated memorial erected for Haiti's earthquake victims. Thousands of bodies are buried here in a mass grave dug after a magnitude 7 earthquake shook the country on Jan. 12, 2010.

"They've forgotten about this place; it should look better than this," Dasny says as she walks past the overgrown grass, rusted metal statues and brittle brush. For the past year, she has been the memorial's groundskeeper, though she has never been paid.

"You must remember the humans buried here. They were just like us and should always be honored, not forgotten," she says. Dasny believes some of her own relatives who were never found after the quake are buried in the grave.

The earthquake's main shock lasted almost 30 seconds. A series of aftershocks soon followed. An estimated 220,000 died, though Haiti's official estimates are higher. Some 1.5 million people were displaced, according to the International Organization for Migration. About 300,000 were injured, and large parts of the country were buried under tons of twisted metal and concrete.

Don't see the graphic above? Click here.

Donors from around the world swiftly pledged billions of dollars in aid and made promises to rebuild. But a decade on, Haitians who survived say they feel forgotten, as much of the goodwill and billions have been lost to waste, greed and corruption.

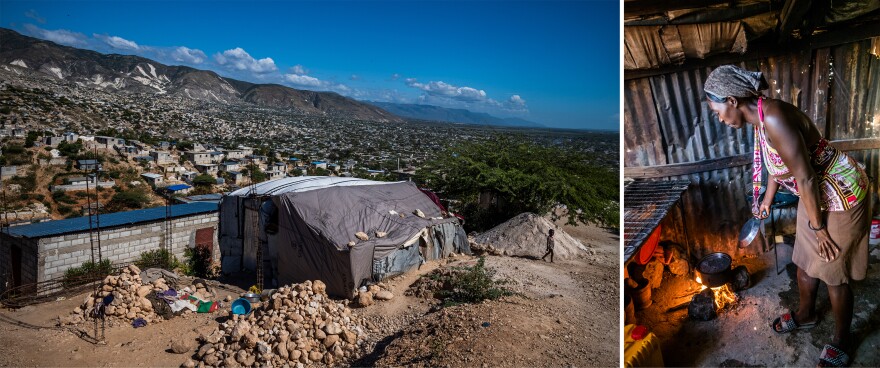

Elizabonne Casseus, 50, is trying to keep her family afloat. She lives with 17 relatives in a small shelter in Canaan, a slum north of Port-au-Prince inhabited by displaced earthquake survivors. Today, the sprawling array of concrete homes and wooden shacks is home to more than a quarter of a million people. There is no running water; there are no sewers and few roads.

Aid, Casseus says, "was good for the people that got it, but not for me."

Her flimsy one-room shack is covered with a gray tarp, stamped with logos of the U.S. Agency for International Development. She bought the cover before coming to these windy hills after spending five years in a squalid tent camp near downtown Port-au-Prince. She had hoped the foreign aid would help her repair her home, destroyed in the quake.

Haiti has long been the Western Hemisphere's poorest nation, and the earthquake only made things worse. In the first year after the quake, the economy contracted by more than 5 %.

Don't see the graphic above? Click here.

Moved by the grisly images of the death and destruction, nations around the world pledged almost $10 billion to Haiti. In addition, $3 billion more was donated to worldwide charities that sent thousands of volunteers to the island. Promises were made for new roads, schools, government buildings and permanent, earthquake-proof housing. Haiti's long-troubled economy was going to be revitalized.

While millions poured into Haiti in the first two years after the quake, giving the economy a boost, signs were emerging that reconstruction wouldn't live up to those promises.

"There were so many opportunities after the earthquake that could have reduced so much poverty," says Kesner Pharel, a Haitian economist. He calls the last 10 years a "lost decade."

By 2012, millions of cubic feet of rubble still filled the streets. More than 500,000 people still lived in squalid tent camps, according to the International Organization for Migration.

High-profile groups created to help coordinate the flow of aid money stopped operating. The Interim Haiti Recovery Commission, set up to streamline and provide transparency for major aid projects and co-chaired by former President Bill Clinton, had already disbanded by the fall of 2011, and less than half of the $4.6 billion pledged to projects was spent.

A 2013 Government Accountability Office investigation found that USAID had underestimated the cost of infrastructure and housing projects, forcing it to substantially reduce the number of homes it originally planned to help build. The GAO also found that most USAID contracts went to non-Haitian companies, leaving local businesses out of any reconstruction boon.

And an NPR investigation five years after the quake found that the American Red Cross, which took in half a billion dollars from U.S. donors, had only built six permanent homes, not the 132,000 it had claimed. The Red Cross disputed NPR's reports and objected to findings of opaque bookkeeping and exorbitant overhead costs.

Economist Pharel says that on top of the botched reconstruction effort, Haiti's constant political turmoil, weak institutions and poor governance squandered international funds and goodwill. The United Nations has struggled in recent years to get donors to fulfill their aid commitments. Last year, it only met 30% of its funding goals to Haiti, according to the U.N.

In recent months, though, citizens have been demanding more accountability from their leaders, not only for the earthquake aid but also for billions of dollars provided to Haiti from an aid program sponsored by Venezuela, known as PetroCaribe. Opponents of Haitian President Jovenel Moïse accuse him of embezzling some of the PetroCaribe funds, and they've taken to the streets demanding he resign. Moïse denies all allegations.

This fall, demonstrations turned violent, leaving 50 people dead and more than 100 injured. Schools and businesses were shut down for weeks. Critical food aid, especially outside the capital, couldn't reach much of the population as demonstrators blocked highways and roads. About a million Haitians suffer severe hunger. Human rights advocates say gangs have grown in the midst of the political turmoil.

But many Haitians are no longer waiting for government or aid groups to build them more permanent homes. Casseus, who relocated to the sprawling slum outside Port-au-Prince, buys sand and stone whenever she has a little extra money so that one day, she can build a more permanent structure on the land she bought.

She admits it is slow going for her and her husband, a car mechanic. "Sometimes he goes out all day long and comes back with no money," she says.

Dasny, the earthquake memorial's groundskeeper, also hopes for a better place to live. For now, she has cobbled together a two-room house on the dusty hillside where she lives by the mass grave. It is made of wooden slats and corrugated tin that rattles and roars with every gust of wind.

Like Casseus, she keeps a large pile of stone and sand outside her door. When she has work or sells one of her goats, she uses the money to buy stones. She breaks the rocks and adds to the piles, getting ever closer to her goal of building a new home.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.