By now, you've probably heard that an army of amateur investors ganged up on short sellers, causing them painful losses while sending shares of the beleaguered retailer GameStop soaring. You also may be asking, OK, but what is short selling?

Short selling has nothing to do with summer wear or workout gear. It's a common but controversial way of trading in financial markets. Let's say an investor decides a company's share price is overvalued and likely to fall.

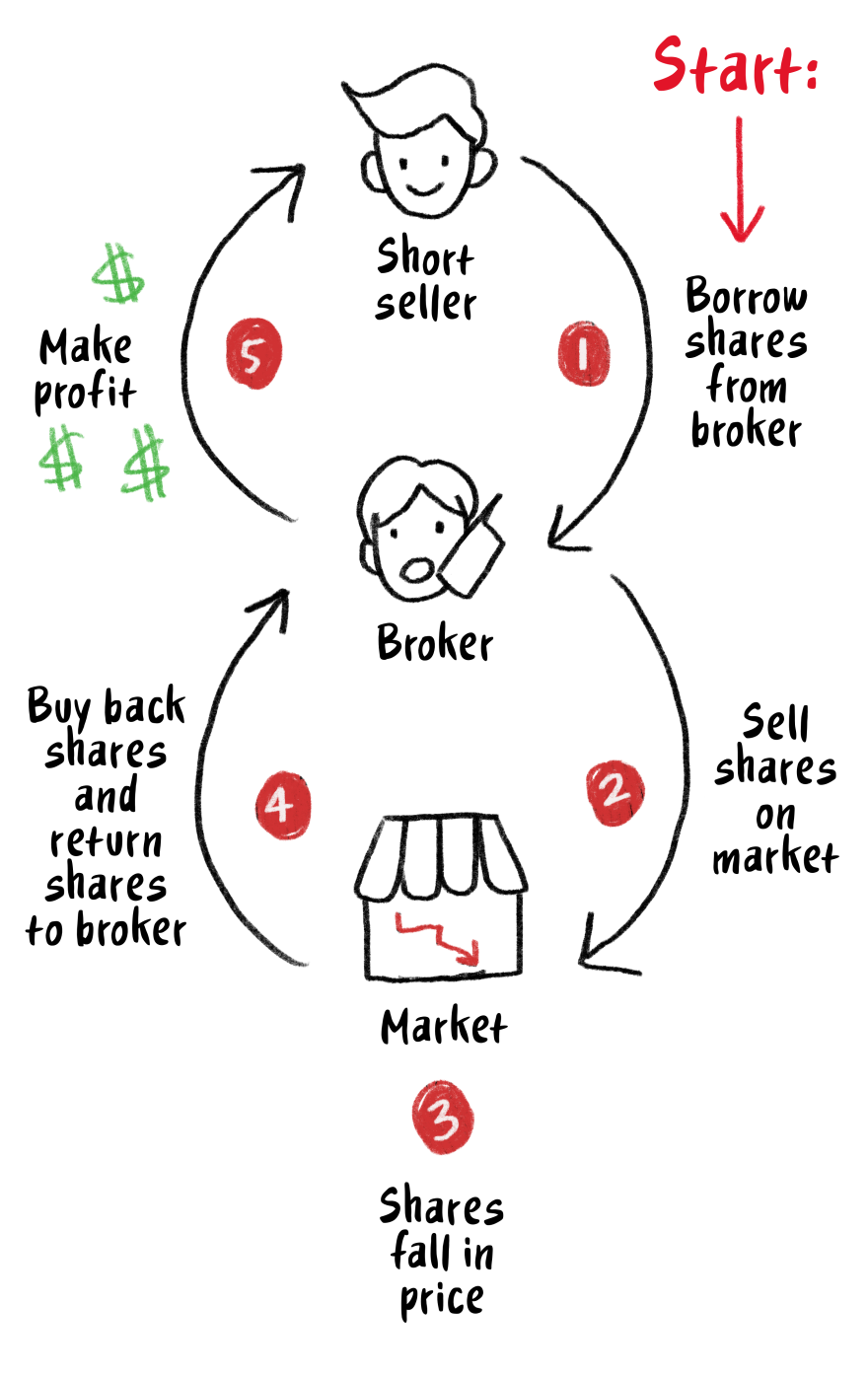

Markets provide a way to make that bet. The investor borrows shares of the company, normally from a broker.

The short seller then quickly sells the borrowed shares into the market and hopes that the shares will fall in price. If the share prices do indeed fall, then the investor buys those same shares back at a lower price.

The short seller then returns the shares to the lender and makes a profit by pocketing the difference.

So what can go wrong?

A lot. Markets are often unpredictable, and short sellers can wind up on the wrong side of their bets.

When a share starts gaining, instead of falling, that's trouble for the short seller. Losses are theoretically infinite since there's no limit to how high a share price can go.

Of course, in reality, shares don't climb forever. But the higher they go, the bigger the loss the short seller sustains.

When that happens, short sellers are in a bind. They need to return the shares they borrowed from the lender. But now, they find themselves buying them back at a higher price, not a lower one. The bet has backfired. In markets, it's called the short squeeze.

How much the short seller loses depends on how much the shares gained since the short seller borrowed the stock.

Take Tesla. Some investors believe the electric-vehicle maker is overpriced, and many tried their hand at shorting the stock last year. It didn't go well for them. Financial data provider S3 Partners estimated Tesla short sellers lost a whopping $40.1 billion last year after the automaker surged more than 700%.

So why short sell?

Short selling is a fairly common feature of markets. It's mostly done by hedge funds and other professional investors.

Some short-sale trades have entered market lore. George Soros, for example, famously shorted the British pound in the early 1990s, making a $1.5 billion profit in a single month, according to one estimate.

But companies obviously hate it when short sellers target them, and short sellers have often been accused of profiting from somebody else's misery.

That's not how short sellers see it, of course. They argue that short selling is an essential part of markets, wringing out inefficiencies and warning others about risky stocks.

There are examples of short sellers who have been proved right in cautioning about corporate wrongdoing or impending doom.

Take the 2008 global financial crisis. In his book The Big Short, author Michael Lewis portrayed a cast of characters who warned of the impending housing crash.

Or most recently, there is the example of Wirecard, a once hot German financial technology company that was repeatedly accused of fraud, sparking strong denials from the company.

The short sellers were proved right. Last year, Wirecard collapsed after disclosing a massive accounting fraud.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.